A firm handshake may still work for some business deals but an increasing number of company agreements are being concluded electronically with a few keystrokes on a computer. Some are even triggered automatically, without human prompting.

Technology is changing the way legal contracts – the cornerstone of conducting business – are made, signed and managed. In many cases, this saves a lot of time, paperwork and money. It’s also more transparent and there’s an added element of security (as in tamper-proof, self-generated ‘smart contracts’ on blockchain technology).

On the downside, the use of unencrypted internet channels such as email can potentially lead to security breaches and there are still multiple legal complexities that need to be explored.

‘We now negotiate via email, video conferencing and Skype and sign electronically without ever meeting face to face,’ says Alexia Christie, partner at Webber Wentzel’s technology, media, telecoms and intellectual property practice.

‘We also need to understand that technology is revolutionising other broader issues of electronic contracting, including around identification of parties, and is forcing us to rethink the very fundamental ideals of what it means to conclude and perform under a contract.’

Christie says SA law recognises the validity of electronic contracts, and has developed rules around where and when a contract is concluded. ‘We also have laws specifically relating to contracts concluded with electronic agents. In other words, technology that automates the conclusion of a contract on our behalf. We’re also moving into a space where biometrics are equivalent to a signature – and our payment system laws are beginning to recognise this.’

The Electronic Communications and Transactions (ECT) Act of 2002 introduced parity with paper for concepts such as ‘in-writing, signature and original’, according to Wendy Rosenberg, director of media and communications at Werksmans Attorneys.

‘The concept of an electronic signature is accommodating of a variety of technology formats, as long as they can positively identify the signatory and their intention to sign the particular document. This development has facilitated and eased business-to-consumer and business-to-business contracts,’ she says. ‘However, certain transactions, such as sale or long-lease of land, wills and bills of exchange still remain outside of the scope of the ECT Act, and are therefore valid only if concluded in hard copy writing and physically signed.’

Technology is not only influencing the way a deal is sealed but also how lawyers and their clients interact. One pioneering example is Legal Legends, marketed as the continent’s (and possibly the world’s) first e-commerce website for affordable legal services to entrepreneurs, start-ups and SMEs. Its unique selling point centres on cost, speed and automation – legal issues are dealt with online, allowing greater immediacy and transparency as the fixed price for each service is clearly stated upfront. In addition to the drafting of company incorporation documents and agreements, services include company registration, intellectual property registration and online video legal consultations.

The SA website, which was launched in early 2016 by two young lawyers, has already inspired one or two copycats, according to co-founder Kyle Torrington. He explains that the service offering combines automation with customisation. ‘What you currently see is only the first step towards true smart contracts. You can browse our website – much like online shopping for, say, shoes on Zando or electronics on Takealot – until you find the type of contract you want. You’ll be sent a digitised questionnaire to establish all the parameters we require to draft the contract,’ he says.

‘We then either draft a custom version of that agreement from scratch, or for some agreements we’ve created an algorithm that assists in turning out an automated version.’

This is where the future of smart contracts lies – in using technology with automatic triggers to self-generate all the contracts needed for certain business transactions.

‘It’s a merger of both corporate governance and automated contract generation, which allows companies more autonomy and, from a pricing point, we come in at a fraction of a fraction of conventional law firms,’ says Torrington.

That said, what exactly makes a contract ‘smart’? It all comes down to automatic self-execution without human intervention, as demonstrated in the low-tech example of the vending machine. ‘It basically works on the “if this, then that” coding principle. One event, like inputting a coin, triggers another event that releases the item from the machine,’ says Christie. ‘The advent of distributed ledger/blockchain technology, such as Ethereum, now brings us to the brink of a new age. Think “Smart Contract 2.0”.’

Whoa, not so fast. Let’s first look at blockchain, the sophisticated sequel based on the vending-machine concept. Blockchain is the technology ‘backbone’ and protocol that Bitcoin and other digital currencies use, according to Deloitte.

‘It’s a distributed ledger that provides a way for information [such as contracts, transactions, assets] to be recorded and shared by a community. Each member maintains his or her own copy of the information and all members must validate any updates collectively,’ states a Deloitte advisory on blockchain. ‘Entries are permanent, transparent and searchable, which makes it possible for community members to view transaction histories in their entirety. Each update is a new “block” added to the end of the “chain”.’

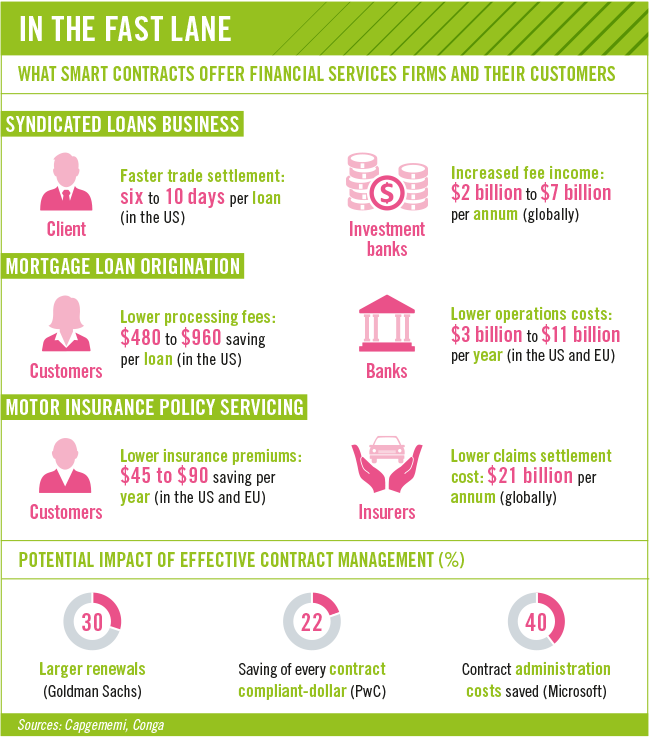

As there’s no need for a central authenticating authority (or middleman), the transaction speed is increased and the cost reduced, says Rosenberg, adding that ‘smart contracts, based on blockchain technology, have the potential to serve most types of contract in a variety of settings – government, business-to-business, business-to-consumer and consumer-to-consumer’.

Financial institutions have been at the forefront of blockchain technology. Ina Meiring, banking and finance executive at ENSafrica offers a recent local example: ‘In 2016, the South African Reserve Bank [SARB], the Payments Association of South Africa, the Financial Services Board, Strate and major banks – including Investec Bank, Nedbank, Absa, RMB and Standard Bank – successfully managed to circulate a smart contract on an Ethereum-based blockchain private network set up among themselves. The institutions involved wanted to develop and test a system for issuing syndicated loans via blockchain. The trial involved the SARB circulating a smart contract to other parties on the test network, which was reported to be successful. The idea is for banks to eventually form syndicates and trade on an electronic exchange with smart contracts.’

However, Ridwaan Boda, ENSafrica director of technology, media and telecoms, cautions that smart contracts are not drafted by legal specialists and instead rely on computer programmers. ‘As with any coding, errors do occur. If a smart contract is coded with errors and is self-enforcing, this could have serious negative consequences for the contracting parties.’ That’s why traditional lawyers will need to understand the technology behind smart contracts and whether regulatory requirements may pose hurdles to their development.

‘Traditional lawyers must, out of necessity, expand their expertise to include fintech – including blockchain and the use of smart contracts – as these are the new legal “frontiers” to be explored and developed,’ says Meiring. ‘We are of the view that other functions and more complex transactions will require a lawyer to assist. It’s not always possible to reduce all of the legal requirements of an agreement into a computer programme code.

‘In addition, parties may want to amend their agreement from time-to-time, which may not be possible unless modification of the smart contract was included in the computer programme code.’

Smart contracts are a natural progression for the legal system, says Christie, who believes the smart contract will ‘fundamentally change’ the way contracts are made, as a result of disintermediation and decentralisation.

‘It will require a new approach to lawyering to navigate and address the complex issues. Smart Contract 2.0 will need the “smart lawyer”,’ she says. ‘The aim is to develop the perfect smart contract that admits no ambiguity, can be interpreted in a binary fashion and anticipates every possible outcome.’

Rosenberg adds that traditional lawyers are set to benefit from this type of technological disruption. ‘If anything, smart contracts facilitate our work by taking away some of the more tedious, routine tasks, while allowing us to grow the value proposition for clients.

‘To put it simply, lawyers are the architects of the rules of the business transaction that a smart contract gives effect to.’