‘Has the time not arrived to build a new smart city founded on the technologies of the 4th Industrial Revolution? I would like to invite South Africans to begin imaging this prospect.’ Those were words from President Cyril Ramaphosa during his 2019 State of the Nation Address.

He later announced the intended development of three smart cities in SA – Nkosi City, which would border the Kruger National Park; the African Coastal Smart City in the Eastern Cape; and Lanseria Smart City in Gauteng.

The plans were far-reaching. Nkosi City, for example, would be driven by agri projects, built in conjunction with housing that would allow residents to live off the land. There was talk of a solar farm and energy derived from biomass. The Lanseria Smart City would take advantage of the adjunct airport and offer mixed housing for between 350 000 and 500 000 people by 2030, as well as commercial and industrial buildings. Much less was known about the African Coastal Smart City, supposedly to be developed between Port St Johns in the Eastern Cape and Margate in KwaZulu-Natal.

These were just some of the smart city projects announced in recent years by various government entities. For example, in October 2021, then Gauteng premier David Makhura spoke about the Vaal River Smart City. Emerging technologies would be the focus, it was said, along with a cannabis industry hub and a hydrogen economy hub.

Meanwhile, in 2022, then Limpopo premier Stan Mathabatha said a R5.46 billion smart city called Nkuna, integrating retail and commercial land use, would be built in the province.

Then there is the Mooikloof development east of Pretoria. Officially launched by Ramaphosa in October 2020, this is the only one of the smart cities that seems to have seen any progress. It’s a public-private partnership, carried out by developer Balwin with a total value of more than R84 billion that will be built in several phases.

Lanseria, however, was supposed to be the jewel in the crown. Yet progress has been slow to say the least. In February last year the Mail & Guardian newspaper reported that ‘the land earmarked for the Lanseria urban development remains just veld’.

At its core, a smart city harnesses digital technology and data-driven insights to enhance urban service efficiency, improve residents’ quality of life and promote sustainable development. These cities integrate various technologies, such as the internet of things, AI and data analytics, to optimise resource use, streamline governance and boost citizen engagement.

The emergence of smart cities brings many advantages. Improved infrastructure and utilities, driven by smart city initiatives, significantly enhance the quality of life. Citizens benefit from more accessible and reliable essential services, including efficient transportation systems, dependable energy grids and advanced healthcare facilities.

Yet the very definition of what constitutes ‘smart’ in a city is a sticking point.

‘The smart city vision, which is presented as the solution to South African challenges, is one of high-speed rail, glossy new buildings and cities, and fast technology. This tech-obsessed approach has led many South Africans to question the value of the smart city in comparison to the country’s pressing challenges, such as the housing crisis, water shortages and the widening poverty gap,’ was how the South African Cities Network, a think tank, explained the issue in a 2020 research paper.

‘Compounding the scepticism about smart cities is the fact that South African cities have different approaches to engaging with the smart city concept. Therefore, before examining smart city issues and projects, it is essential to understand the role of smart cities in a South African context, given that cities, literature, legislation and policy have not defined this understanding.’

A report by the department of industrial engineering at Stellenbosch University in 2023 sums up the issue succinctly. ‘Smart city projects in South Africa seem to be very few and far between, as there is no integrated national smart city strategy. For smart cities to be successful and efficient, governments will have to develop a strong presence in ICT and increase the use of IoT devices,’ it states.

Of course technology has a vital role to play … but how the latest high-tech is deployed and more importantly how the data derived from it is utilised seems to be far more important.

‘The City of Cape Town showed the willingness and ability to employ technology to overcome severe challenges during the 2018 drought,’ states the Stellenbosch University research paper. ‘This extreme drought was a catalyst for smart water management. The city council and residents were forced to find better ways to manage their water usage as Day Zero appeared on the horizon. The city management introduced smart utility technology, using smart remote meters to measure and manage strategic points.’

The report says researchers had found that the use of these smart technologies enabled the city council to reduce water use by 10%.

The tech-heavy avenue is echoed by Jan Bouwer, chief solutions officer at BCX, in an opinion piece. ‘What the global smart city leaders have in common is that they have built on and developed existing infrastructure, transforming it iteratively. SA is well positioned to adopt this approach in concert with our development of new cities,’ he writes.

‘SA’s “unsmart” cities are ripe for digitalising. Our biggest cities have a lot of the essential infrastructure that forms a solid base for a smart city conversion, including high levels of smartphone penetration, high-speed fibre networks, CCTV camera networks and, increasingly, internet of things sensors, solar power and rainwater-harvesting systems.

‘CCTVs in the city provide data that can be used to analyse traffic volumes and other variables that affect congestion, and need to be considered in city planning. Capetonians have already experienced how this can be used to their advantage – recent data showed the city should scale back on the number of buses on the road. Johannesburg and Pretoria also house wide CCTV networks, which could be used to collect and analyse data.

‘Leveraging the infrastructure already in place would be less costly and it would enable us to start delivering on our smart city vision more rapidly.’

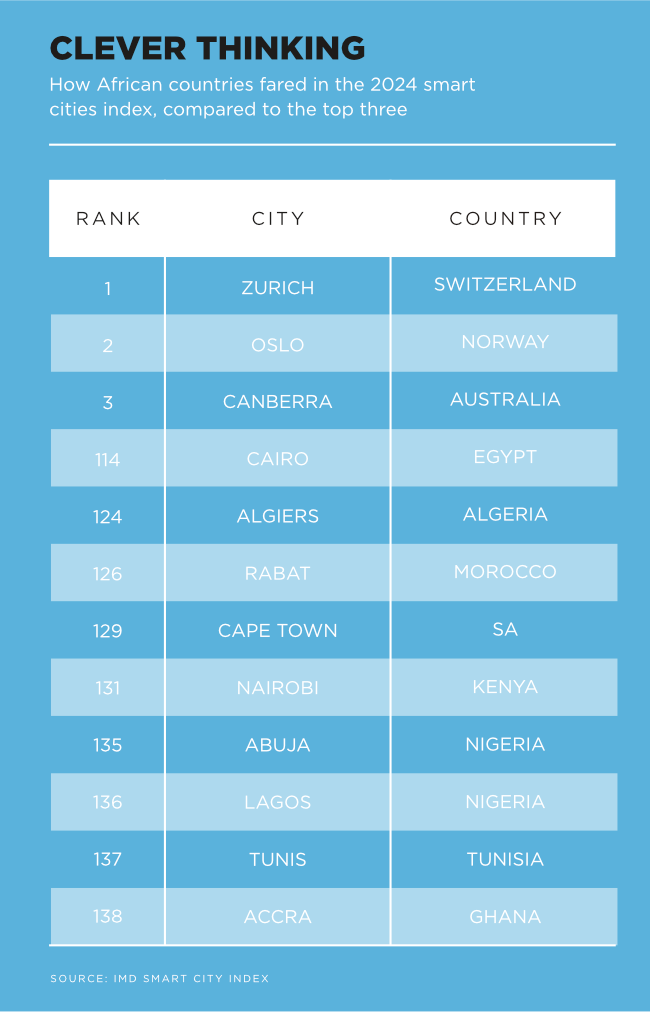

Yet there’s almost a sense that SA is over-reaching in the eagerness to be counted among the likes of Seoul or Zurich. Perhaps there are simpler ways to, well, be smart. In October last year Nancy Odendaal delivered a lecture at UCT titled Reframing African Smart Urbanism. ‘We must differentiate African cities from the broader smart city narrative, as the context and challenges are unique,’ she said. ‘True transformation through technology lies in empowering individuals in their daily lives’.

She highlighted the role of technology in everyday decision-making for disadvantaged communities, and highlighted several specific themes, ‘including the power of disruptive platforms such as ride-hailing and food delivery apps to boost informal economies in Africa’.

Perhaps the best approach for Africa is to draw on the experiences of other places that have learnt the smart city lessons the hard way. Cities such as Singapore, for instance. In 2019, the inaugural IMD Smart City Index ranked it No 1 in the world (it was No 5 in the 2024 index).

ITWeb interviewed Rahul Ghosh, director of Enterprise Singapore for the Middle East and Africa, in August 2023, during his participation in a government visit to SA. Enterprise Singapore forms part of the Ministry of Trade and Industry in Singapore. Ghosh told the website that Singapore has learnt that starting small is important. ‘It doesn’t need to start at the city level; it can start at a small municipality level, at an estate level, or even just start with smart building.’

He suggested that a country could initiate its smart city journey by implementing sustainable and resource-efficient technologies and solutions. ‘For example, this can start at a municipal level with solutions that are able to detect water leakages. There can also be deployment of smart street lamps, which won’t only provide light but also be used to capture data for traffic. There also needs to be provision of WiFi solutions, especially where there’s no WiFi or internet connectivity through fibre.’

For a local, practical and positive example of starting small, look at tiny Clarens in the Free State. While the entire country was experiencing load shedding, Clarens – thanks to its ‘smart’ electricity load-management project – kept all the lights on. A smart meter at the town’s main supply point sends real-time statistics of the town’s current demand to Eskom every 60 seconds, allowing constant monitoring, and enabling the residents to manage their own electricity usage through group load curtailment.

The collaborative efforts of the entire community to reduce electricity consumption when requested through social media and WhatsApp alerts was a resounding success. Clever ideas crop up in all sorts of places.