Please, please tell us you’re not a ‘123456’ or ‘qwerty’ person. And if you are a ‘password123’ or ‘1qaz2wsx’ person, we don’t want to know. As password-management service NordPass pointed out in December, ‘year after year, we see the same passwords at the top of the “worst passwords” list’. They’re right, of course. According to their research, the world’s most popular digital passwords contain all the obvious and easy-to-guess combinations or strings of letters on a keyboard. Even the most obvious password – literally, ‘password’ – remains very popular, with 830 846 people on the NordPass list still using it to safeguard their email, banking and social media accounts.

So why do people keep using obviously weak passwords? ‘The first reason is that they are easier to remember,’ says NordPass. ‘Simple as that. Most people prefer to use weak passwords rather than strain themselves by trying to remember long, complex ones. Unfortunately, it also means they use the same one for all their accounts. And if one of them ends up in a breach, all other accounts are automatically compromised too.’

The problem with passwords is that, to work properly, they have to be easy to remember and hard to guess… And they also need to be unique. According to password manager Dashlane, the average US consumer has 130 accounts linked to a single email address. It’s impossible to remember 130 different strong passwords, which is exactly why so many people across the world tend to use the same log-in credentials (same email, same password) across multiple accounts. And then, when one of those accounts is hacked, all of those accounts are hacked.

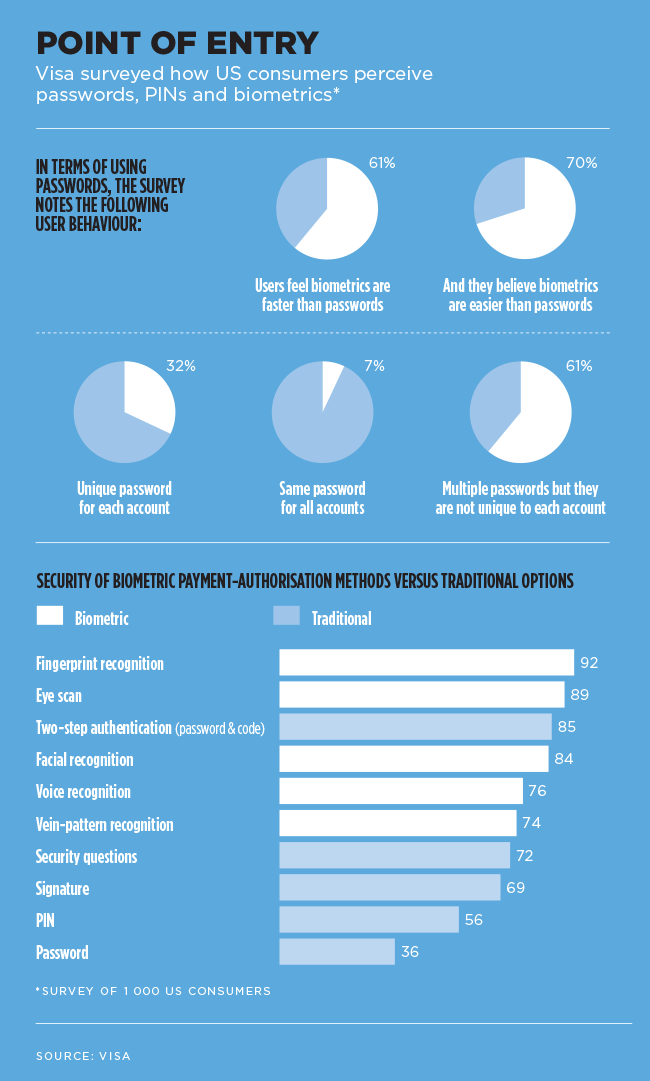

There is, of course, a better option – and you probably use it every day on your smartphone. Biometric access uses facial or fingerprint recognition (or any unique physical attribute, from iris scanning to gait analysis), which cannot be typed on a keyboard, cannot be recreated and cannot be compromised.

A report by MarketsandMarkets estimates that the global mobile biometrics market will be worth close to $65.3 billion by 2024, while research by Gartner estimates that by the same year, 60% of large businesses and almost all medium-sized companies will have halved dependence on passwords, as passwords are steadily replaced by biometric access.

‘Passwords are no longer a sufficient security barrier,’ says Raymond Liao, MD at Samsung NEXT Ventures. He believes that biometrics will replace passwords simply because ‘they are so secure and convenient’. Liao expects different types of biometrics to be used for different applications. ‘Let’s say you want to unlock your phone,’ he says. ‘Most people would prefer a convenient hands-free approach, and camera-based facial or eye recognition would be the preferred way. But the face is not as secure a modality, and you might want to use fingerprint to authenticate a financial transaction.’

That’s why smartphone makers prefer fingerprints (by some estimates, as many as 57% of mobile apps now feature a biometric log-in option); and why Malaysia’s KL International Airport recently piloted a facial-recognition system to take travellers through the airport’s various touchpoints, from baggage drop to security checks, without needing to present a physical passport or boarding pass. Both are examples of biometrics offering – as Liao puts it – a ‘practical combination of security and convenience’.

Biometrics are not new. Tenants and employees have been using fingerprint access to enter buildings for years now, and Apple’s Touch ID has been sitting on your smartphone since 2013. But what is new is the integrated and everyday nature of it all. ‘Until now, biometric technologies have been the unsung hero for enterprises, despite their high levels of user acceptance, and the fact that it’s almost impossible to “lose” your biometric ID – which means a dramatic reduction in help-desk calls for password resets,’ Péter Györgydeák, CEO of Hungary-based biometrics company BioSec, said at the launch of Fujitsu’s extended range of PalmSecure biometric security solutions, which use a central matching server to eliminate the need for multiple-user enrolment across different locations, devices, applications or services. ‘By teaming up with Fujitsu, we have a joint opportunity to help biometrics reach their full potential in the workplace,’ he added. ‘The new expanded PalmSecure portfolio puts biometric ID within reach of just about any use case, and makes great financial sense for any organisation that’s serious about security.’

PalmSecure is contactless – which means it combines Fujitsu and BioSec’s technology to authenticate users based on the unique pattern of their palm veins. The companies claim that the advanced authentication algorithm produces false acceptance rates below one in 10 million and false rejection rates of one in 10 000, which would make it one of the most accurate biometric authentication systems currently available.

‘Biometric ID and palm-vein technology in particular are lifting IT security to a higher level,’ says Oliver Reyers, head of biometrics at Fujitsu in Europe, the Middle East, India and Africa. ‘There’s no need to remember – or regularly change – complex passwords, and this makes it so much more convenient for users to access secure assets and applications. Fujitsu has applied the principle of simplicity to solution development and deployment. This has resulted in an expanded portfolio of biometric security solutions that make it easier for organisations to implement biometric identification. Fujitsu’s PalmSecure biometric recognition algorithm delivers ultra-low false acceptance rates, while central enrolment processes ensure that users can’t bypass security simply by creating multiple IDs.’

It all sounds like the perfect security solution… But of course it’s not. Remember earlier when we said biometrics cannot be recreated or compromised? That wasn’t entirely true. A Vietnamese cybersecurity firm has already cracked Apple’s Face ID using a mask made with a 3D printer, silicone and paper tape, and the Samsung Galaxy S10’s ultrasonic fingerprint sensor has been fooled by 3D printed fingerprints more than once.

It gets worse. In 2014 a hacker named Starbug (or Jan Krissler to his mum) stunned a cybersecurity conference when he revealed that he’d created a fingerprint of Germany’s Secretary of Defence Ursula von der Leyen using only a few high-resolution photographs (including one that appeared in a media release issued by her own office). He’s since been able to fool the iPhone’s supposedly impenetrable fingerprint sensor using a fake fingerprint made from wood glue, and bypassed a hand-vein scanner using a fake hand made from beeswax.

Then in 2019, news broke that a database breach at Suprema BioStar 2, a biometric security platform used by the UK’s Metropolitan Police, had exposed more than a million fingerprint and facial-recognition records. It was, in many ways, far worse than if a million online passwords had been uncovered. As security expert Matan Or-El told SC Media at the time, ‘unlike usernames and passwords, biometric information such as fingerprints and facial recognition records cannot be changed. And because Suprema is connected to thousands of organisations across the world, this compromised data has the power to rattle the entire supply chain’.

This March, it happened again. A Brazilian server containing records of about 76 000 unique fingerprints was exposed, with researcher Anurag Sen (one of those who detected the breach) telling CNet that while bad actors may not do anything with the information immediately, ‘it might be that in the future they’ll find a way to exploit it. Fingerprints are permanent throughout life’.

And that’s the risk with biometrics: if a biometric database is compromised, the effects can be forever. Passwords can be changed or updated, but there’s no changing your fingerprint or your face. Stolen biometric data can be misused for a lifetime if it falls into the wrong hands.

Two-factor authentication is one way to work around this, requiring the user to produce two different factors: something they know (for example, a password) and/

or something they have (such as a bank card) and/or something they are (a biometric feature, for instance).

So while biometrics are a powerful element of online security, on their own they have their flaws. André Immelman, CEO of aiThenticate, highlights those flaws, pointing to the boom in identity theft. ‘Much of this has to do with the false sense of security that biometric features on smartphones tend to foster,’ he says. ‘Fingerprint, facial recognition, retinal and iris-scan systems built into mobile phones add absolutely nothing to the security of a transaction.

‘That is because every on-device biometric is premised on simple faulty logic: the user is asked to tender a fingerprint or faceprint or voiceprint as “proof” of their identity, when the device has absolutely no way of knowing whether the biometric actually belongs to that user.’ He argues that only through a process of authentication, identification, anti-spoofing, verification and authorisation can a security system be considered complete.

Even then, it all falls apart if the typed password in that chain is something like ‘123456’ or ‘qwerty’.