For Arianna Renee, the numbers just didn’t add up. The 18-year-old Miami-based Instagram star – known to her 2.6 million followers simply as @arii – had decided to launch her own clothing line, hoping that her enormous follower base would translate into sales. The production company had told her that she needed to sell at least 36 T-shirts for the line to be continued. Renee failed to hit the target.

‘The people who I thought would support me really didn’t, nor did they share any of my posts (all I asked for),’ she wrote in a long – and hastily deleted – post. ‘Sounds bitchy but like, no shade to anyone, I’ve supported everyone’s music or whatever they’ve asked for my support on, and I couldn’t even get it in return.’

@arii’s failure came in May 2019, barely a month after fellow influencer Gabbie Hanna (@gabbiehanna, with more than 3.5 million followers) had shared photographs of herself at the Coachella music festival – photographs, it turned out, that had been faked using a combination of Photoshop and a friend’s back garden.

Argentine travel influencer Martina Saravia (@tupisaravia) then went viral that September when some of her 300 000 Instagram followers noticed that many of her photographs featured the same cloud patterns. (She admitted to editing the images, and – because the internet has a strange sense of justice – is now developing an app that will allow others to insert fake skylines into their own photos.)

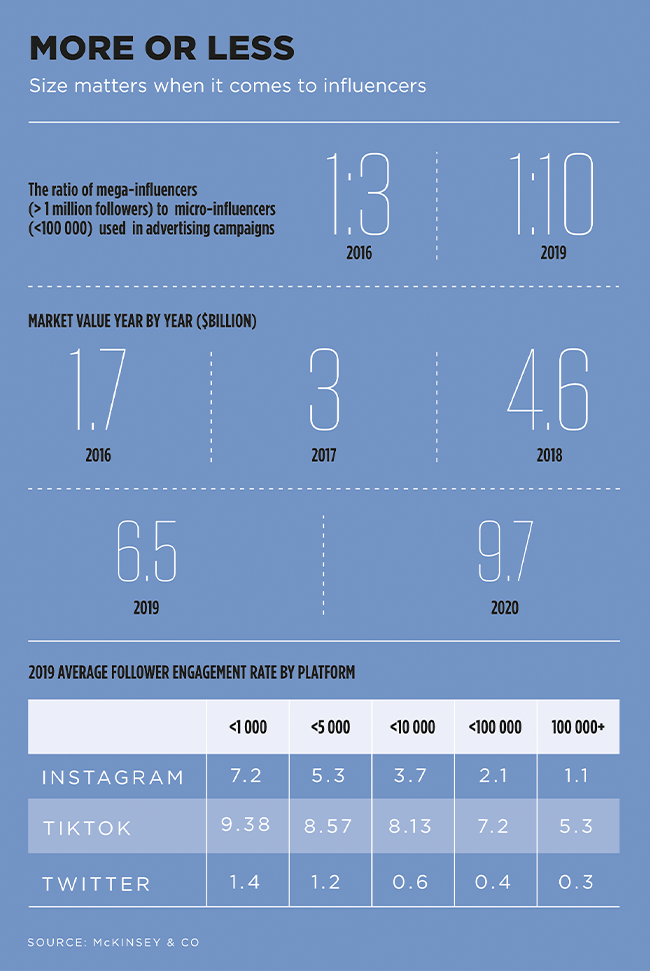

By the end of 2019, the influencer bubble was well on its way to bursting. In a market where influencers in the US were being paid $10 000 or more for a once-off endorsement post (in SA the going rate remains anywhere from R500 to R10 000), brand managers were increasingly asking whether social media influencers were really all that influential after all. Many, it seemed, were simply famous for being famous; and rather than providing authentic recommendations, they seemed more focused on scoring freebies from marketers who should have known better.

Joe Nicchi knew better. Nicchi is a bit-part actor whose credits range from small gigs on TV shows you’ve heard of (ER) to roles that paid the bills (Vampire Zombie Werewolf), and whose day job is running a soft-serve ice-cream truck in Los Angeles. In July 2019 Nicchi hung a sign on his truck that said, ‘influencers pay double’, declaring on Instagram that he would ‘never give you a free ice cream in exchange for a post’. Nicchi’s post (tagged #InfluencersAreGross) went viral, and – based on the online buzz – his business boomed. ‘We’re the anti-influencer influencers,’ he says in an interview with the Guardian. ‘I don’t think my kid’s school accepts celebrity photos as a form of tuition payment.’

Yet social media influencers remain an important part of the marketing landscape, selling their audiences to advertisers in much the same way newspapers, radio stations, TV channels and magazines do. And while they are similar to a standard celebrity endorsement, in most cases they’re cheaper and (hopefully) less likely to cause high-profile public embarrassment.

‘An influencer is a “person brand”,’ says Carla Enslin, co-founder of the Vega School of Brand Leadership. ‘As a brand manager, when you work with influencers you need to realise that it’s a strategic alliance, so you’re going to apply the same principles as you would with any other alliance. To what extent do you have unique identities that are aligned? To what extent is the content that the individual produces aligned with yours? To what extent is it authentic and sustainable? All those principles would apply.’

In mid-March last year, Ruan Fourie of digital marketing company Starbright Solutions made the case that influencer marketing puts your business where the audience will notice it. ‘The main advantage of digital marketing is that it’s reaching people where their attention already is: social media, or simply the screen of their smartphone,’ he writes. ‘By working with influencers, you can pinpoint your marketing efforts much more effectively than by running an ad on Facebook. Even if that Facebook ad is targeted, it won’t be as targeted as speaking to an influencers’ audience via the influencer.’

For Enslin, however – and for many in the marketing and brand-management world – the question has moved from ‘what is an influencer?’ to ‘why is an influencer?’. In a time of COVID-19, when millions of people were stuck at home in national lockdowns, the public steadily lost its patience with out-of-touch celebrities.

Comedienne Ellen DeGeneres faced a backlash in April after complaining about being quarantined in her $27 million California mansion. ‘One thing that I’ve learned from being in quarantine is that, people – this is like being in jail, is what it is,’ she said, to the bemusement of people who were using kitchen tables and ironing boards as their new home offices. Then, in October, Kim Kardashian took a social media hiding after tweeting about her 40th birthday party, held on a private island where she and her ‘closest inner circle’ could ‘pretend things were normal just for a brief moment in time’. This while thousands were dying and millions were losing their jobs.

Is the age of the influencer over? Enslin doesn’t think so. ‘It’s still a thing, in as much as the influence of social media is still a thing,’ she says. ‘But what has shifted is the recognition of the value of nano-influencers: individuals with far fewer followers but well-crafted identities and their own sense of uniqueness.’

The likes of @arii and @gabbiehanna – let alone Ellen (92 million Instagram followers) and Kim (188 million) – may have provided marketers with the reach of massive online audiences, but so-called small-scale ‘mommy bloggers’ with a loyal audience of a few thousand followers come with the promise of higher audience engagement. As Starbright’s Fourie points out, ‘despite popular belief, the reach is not a measuring yard for any good influencer marketing strategy’. Instead, it’s about the engagement.

‘Nano-influencers’ communities might be smaller at 1 000 to 5 000 followers, but their level of engagement with those communities is often stronger,’ says Enslin. ‘They have more engaged followers who really connect with what the influencer stands for, and who follow them more intensely than they would others. It’s that degree of engagement that brands are interested in and hope to leverage.’

But while nano-influencers may seem like a seismic market shift, it’s just a new, tech-orientated way of driving word-of-mouth marketing. In 2015 a Nielsen global survey found that 83% of consumers trusted the recommendations of friends and family over other forms of advertising; while a 2013 Nielsen report noted that African consumers in particular trusted endorsements from families and friends more than any other advertising. The opportunity for marketers is that, while those micro-trendsetters used to be almost impossible to find and harness, social media platforms and digital technologies now enable companies to leverage, measure and – dare we say it – influence their influence.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the concept of social media influencers didn’t die; the focus merely shifted from reach to engagement. That shift had been bubbling under for months, but – as with so many tech trends in 2020 (e-learning, e-commerce, remote learning) – the massive social and economic disruption of the pandemic simply accelerated the change.

‘If your engagements as an influencer depended on physical contact, then you were in trouble in 2020,’ says Enslin. ‘But the influencers who entered the crisis with a firm understanding of what they do and why they do it would have returned to their reason for being an influencer in the first place, and their content creation would have followed. They would have realised, I can’t attend any events so I’m going to have to innovate to hold my brand. ‘Influencers who had less depth or texture to their identity, and who had no real sense as to why they were doing what they were doing, would have found themselves in a very troubled state.’

Enslin maintains that, from a branding perspective, identity systems form the basis of business models. ‘If you don’t understand why you do what you do, this is a very trying time to navigate – no matter whether you’re an influencer or a large business. The advantage for nano-influencers is that they’re agile enough to change, if they understand why they exist in the first place.’

And if that reason is simply to sell T-shirts, fake a weekend at Coachella or score free ice cream, then it’s perhaps little wonder that marketing insiders are moving on to more engaged – and more engaging – alternatives.