We’ve seen the future… And it looks like a cardboard toy. If anything, it resembles the sort of cut-out-and-keep craft project you’d expect to find on the back of a breakfast-cereal box. It’s called, appropriately enough, Google Cardboard, and it’s the first big step in making high-tech virtual reality (VR) accessible to anyone who owns a smartphone and a pair of scissors.

The platform uses a fold-out cardboard head-mount, which serves as a set of viewing goggles when you slot your smartphone in the front. You can either build your own viewer using a cheap DIY kit (the design is available for free on Google’s website), or you can buy a pre-made one (again, google the details). Then simply download the 72.1 MB app and start enjoying a rudimentary look into the world of VR.

The platform was created by two Google engineers during their free time, and was introduced at a developers conference in 2014. By the beginning of this year, Google claimed that it had already shipped in excess of 5 million Cardboard viewers, the app had been downloaded and installed more than 25 million times, and in excess of 1 000 compatible apps had been built.

Cheap, easily accessible VR has arrived. The question now is what can businesses do with it? And how big is the market really?

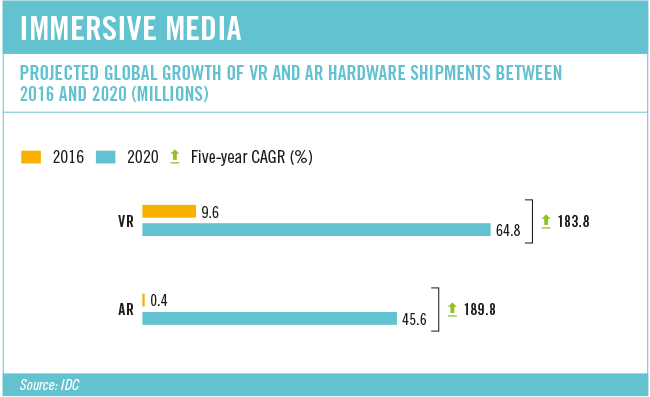

The market, to answer the second question, is huge. That’s according to the first virtual and augmented reality (AR) forecast from market research firm IDC, released in April, which projects that hardware shipments in the combined device markets will surge past 110 million units in 2020.

‘Worldwide shipments of VR hardware will skyrocket in 2016, with total volumes reaching 9.6 million units,’ the report claimed. ‘Led by key products from Samsung, Sony, HTC and Oculus, the category should generate hardware revenues of approximately $2.3 billion in 2016.’

That’s not even counting Google Cardboard. The IDC says that it was ‘specifically not forecasting Google Cardboard-based products in its totals, nor any other viewer accessory that lacks electronics’. The firm identified three major device categories across the AR and VR markets: screenless viewers that use a smartphone to drive the AR/VR experience (such as Samsung Gear VR); tethered head-mounted displays (HMDs) that use a smartphone, PC or gaming console to drive a head-worn display (such as Oculus Rift); and standalone HMDs, where the processing is built into the head-worn display (such as Microsoft HoloLens).

‘In 2016, the first major VR-tethered HMDs from Oculus, HTC and Sony should drive combined shipments of more than 2 million units,’ IDC vice-president for devices and displays Tom Mainelli said in a statement. ‘When you combine this with robust shipments of screenless viewers from Samsung and other vendors launching later this year, you start to see the beginning of a reasonable installed base for content creators to target.’

According to IDC China research manager for client system research Neo Zheng in a separate report: ‘What started as a great concept, VR is quickly becoming reality for consumer and business applications. With the participation of major global manufacturers, the VR market is set to enjoy rapid growth in the second half of 2016.

‘This results in upstream and downstream benefits, with VR chip/screen suppliers providing more specially designed components and video game developers offering more VR content. We expect the VR ecosystem and user demands to dramatically change in the coming years.’

In another media statement (predictably, there are plenty of experts with a great deal to say about VR and AR right now), Ernst Wittmann, Alcatel regional manager for Southern Africa, pointed out that smartphone manufacturers – and not gaming console makers or VR specialists – hold the key to mainstream consumer acceptance of VR devices. ‘Smartphone manufacturers will unlock affordable VR for the average consumer. In much the same way as smartphones have put an affordable camera, GPS and powerful computer in our pockets, they will give most of us our first taste of VR,’ he said.

Wittmann cited numbers released by research firm Strategy Analytics, which project that more affordable smartphone-powered devices will account for 87% of VR devices shipped in 2016.

‘This makes sense since the premium devices are aimed at an early adopter audience, primarily the gamer, that doesn’t mind spending at least $500 on a new gadget. Smartphone manufacturers will offer a lower entry price and tie their VR offerings to a device that their customers already own,’ said Wittmann. And that’s just virtual reality. Its cousin, AR, offers even greater scope for growth. First, though, it’s important to clarify the difference between the two.

VR is an immersive 360-degree simulated environment, such as the experience offered by Nissan ahead of this season’s UEFA Champions League football final in Milan. In a VR setting at the city’s fan zone, members of the public were invited to experience (through a simulated situation based on the as-yet unreleased PlayStation VR system) what it feels like to drive the new 2017 Nissan GT-R through the streets of Milan.

AR is a live view of a real-world environment, with an added layer of computer-generated input (such as sound, video, graphics or GPS data) superimposed on top of it. Your case study here is the AR catalogue published by furniture store IKEA in 2013, which allowed shoppers to visualise – using overlaid images – how certain pieces of furniture would fit into their homes.

However, there’s more to it than immersive computer gaming or home-design tools. Temitope Esan, product manager for AR at Nigerian digital media firm Terragon Group, believes that AR will help brands create better engagement channels with their customers.

‘The opportunities for AR are endless for any organisation as it seeks to enhance our real-world experience. By superimposing digital information on real-life objects, individual customers are given a personalised and rich user experience that enables them to easily connect to a brand’s offerings,’ he says.

‘With the use of AR, brands have an in-depth understanding of their customer behaviour that will increase affinity, user engagement and interaction with their various product/service offerings.’

Practical examples of these ‘endless possibilities’ are already available. In January, African travel operator Matoke Tours produced a ‘virtual gorilla’ travel brochure, with six virtual chapters to view on travel offerings in Uganda. The app allows you to – virtually – track gorillas in the Bwindi rainforest or explore Uganda in a hot-air balloon, among other activities.

‘This app enables us to convey the intensity and emotion of the travel experience before the journey has even started,’ Matoke Tours Uganda director Wim Kok said at the product launch. ‘Travellers are then better decide which excursions they want.’

VR/AR has also offered a similar advantage to real estate and property agents who offer prospective buyers a virtual tour of a home or building and allow those buyers to obtain a sense of the space without actually setting foot inside.

In SA’s mining industry, VR is being used to train the next generation of engineers and technicians.

‘In mining, employing spatial data technologies presents a great opportunity for improvements, from operational to functional capabilities,’ says Dave Drinkwater, principal of technical management systems design at Anglo American.

‘For instance, this allows us to train mine managers and employees in various ways by providing visual interpretations of business decisions in virtual environments. We can give users various business problems to solve and require them to make certain decisions to address these. By showing them how their actions impact the mine, it gives users the opportunity to learn freely without having to be concerned about making costly mistakes.’

Anglo, through its Kumba subsidiary, has invested heavily in a facility at the University of Pretoria. It has a 4m-high, 10m-diameter cylinder with a 32m circular screen, and incorporates five different projectors that project 3D images onto the screen in 360 degrees. This allows for more than 30 people in the room to all experience the same visual effect in 360 degrees. It’s being used by the university’s mining engineering department to teach key skills, including mine design as well as mine safety.

‘With the use of spatial data technologies, we are not trying to replace the expert but rather enhance the decision-making capabilities of the expert by providing data in the most realistic way,’ says Drinkwater.

Between Italian test drives, Ugandan gorilla encounters and South African mining training, virtual reality has become an actuality.