The explosions were heard across the world. At 1:07 pm local time on 23 April 2013, trusted news agency Associated Press (AP) broke the news via Twitter. ‘Breaking: Two Explosions in the White House and Barack Obama is Injured.’

As expected, panic ensued. Thousands of people retweeted the news. The markets reacted within seconds, with the Dow Jones industrial average instantly dropping 150 points. Globally, investors and ordinary citizens waited anxiously for the follow-up report. It never came. The tweet was fake.

‘The president is fine,’ White House spokes-person Jay Carney insisted. ‘I was just with him.’ AP confirmed that its Twitter account had been hacked. ‘The tweet about an attack at the White House is false.’ The world breathed a sigh of relief, the markets bounced back (the Dow actually ended the day up 152 points), and the whole drama was quickly forgotten. The lesson, however, was not.

‘This is yet another reminder that social media isn’t simply banal messages about breakfast between teenagers, but that it can have massive, real-world consequences,’ Jeff Hancock, a Cornell University communications and information science professor, told USA Today in the wake of the AP incident.

‘Our trust of social media has reached new levels. [Wall Street’s] response also highlights that humans have a built-in truth bias to believe what others say. Although there is a lot of suspicion about the internet in general, the truth bias is alive and well with social media.’

April 2013 was a long time ago – an eternity in social media years. Back then, Twitter had about 218 million monthly active users worldwide. Four years on, in Q2 2017, it was averaging 328 million active users, according to Statista. As social media’s footprint grows, so does its potential impact – and its vulnerability to abuse.

‘Apart from its ability to influence political leanings and galvanise movements, social media is being harnessed to gather all sorts of data and information around the clock,’ says Colin Thornton, CEO of IT support firm Dial a Nerd.

‘Everything that we do and say online is recorded and leaves behind a digital footprint, which certain companies are carefully tracking to benefit their own commercial or political agendas. Arguably, the availability and sheer volume of all this data can leave people and enterprises vulnerable to abuse.’

To illustrate just how vulnerable companies are to damage delivered via Twitter storms and social media, Thornton shares a more recent example.

‘After US President Donald Trump signed an executive order that banned immigrants from seven Muslim-majority countries, protests swept across the nation,’ he says. ‘Soon after, the Taxi Workers’ Alliance supported those voicing their opposition to Trump’s policies at New York’s John F Kennedy International Airport by asking its members to halt work at the airport for a period.

‘Shortly after the TWA said the stoppage would end, Uber tweeted that it had turned off surge pricing at JFK. Almost immediately, accusations that Uber was attempting to profit from protesting cab drivers – by making it cheaper for consumers to Uber – began flying on Twitter. It didn’t take long before there were calls to #DeleteUber – and indeed, many users began posting screenshots on social media of themselves deleting the Uber app or registering for competitor Lyft. Within days, Lyft surpassed Uber in daily app downloads for the first time ever. Uber subsequently had to find ways to repair considerable brand damage,’ says Thornton. In the space of just one week, the #DeleteUber campaign inspired 500 000 users to do exactly that – delete their Uber accounts.

If that’s the impact social media can have simply by persuasion, imagine the damage that can be done when – as happened to AP – a company account is hacked. Major brands such as Burger King, Pakistani dairy company Haleeb Foods and entertainment firm HMV have all suffered social media hacks, with varying levels of brand damage.

In Burger King’s case, its entire Twitter account was reskinned to make it look like rival McDonald’s, though the story ended happily enough – with McDonald’s tweeting its support and sympathy, and with Burger King gaining about 60 000 new followers. The other episodes didn’t go so well.

Last December, Haleeb Foods’ Facebook page was defaced and locked down by its own social media agency (which had all the necessary passwords), revealing to all the world that the agency had not been paid for its services for the previous several months.

During a 2013 corporate restructuring process, employees at HMV took over the firm’s Twitter account (which, of course, they all had access to already) to ‘live-tweet from HR’ as they were being retrenched. Sample Tweet: ‘Just overheard our marketing director (he’s staying, folks) ask, “How do I shut down Twitter?” #hmvXFactorFiring.’

Data security breaches, says Harriet Cohen, senior product manager at software company Digital Guardian, can be ‘devastating in terms of cost and reputation so efforts are rightly directed at protecting the perimeter of an organisation’s IT systems from unauthorised intruders. However, the threat that is harder to guard against is within’.

‘Spotting security incidents arising from within the firm is particularly tricky because the attacker may have legitimate access,’ she says. The Haleeb Foods and HMV cases provide perfect examples. ‘If the credentials being inputted are valid, the same alarms are not raised as when an unauthorised user attempts entry from the outside.’

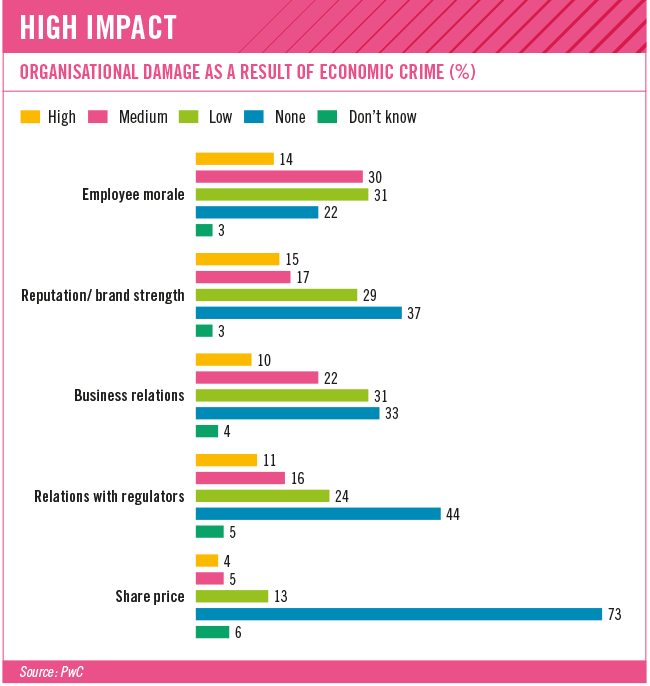

There’s not much you can do to secure your home against someone who has the keys to your front door. Similarly, it would appear that companies can’t do much about insider IT security threats – or they’re simply ignoring the threat. In its annual SA Crime Survey report, PwC found that ‘many boards are not sufficiently proactive regarding cyberthreats and generally do not understand their organisation’s digital footprint well enough to properly assess the risks’. This despite the fact that they have a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders in terms of cyber risk.

‘More often than not, information presented to boards is linked to compliance and external audit requirements. Internal audit and internal risk functions need to further develop their capabilities in identifying and dealing with cyberthreats, which will in turn impact cyber-readiness programmes.’

‘The truth is, it’s not just an IT matter,’ says Cohen. ‘While the IT department is central to enabling access to information, they really just provide the tools. It’s down to the C-suite, managers, HR, legal and IT to work together to empower and engage employees. Trust is a key factor because there needs to be an atmosphere in which management can take advice they don’t necessarily want to hear, and in which an employee can speak up without fear of reprisal.’

Cohen warns about the threat of former employees – some of whom will leave a company with its ‘digital keys’ in their pocket. It doesn’t have to be someone from the IT team – after all, this relates as much to branding/marketing as it does to cybersecurity. Many marketing team employees walk out of jobs still knowing all the company’s default passwords, still having Facebook admin rights, and still having access to sensitive Google Analytics data.

‘When an employee leaves the company, this should automatically set off a series of security measures,’ says Cohen. ‘Disgruntled employees are a key source of security breaches. Even if the parting is amicable – and often it is not – employ-ees leaving the company may be tempted to take information with them to their next employer. When an employee leaves the company, immediately terminate all employee accounts. Remove employees from all access lists, and ensure they return all access tokens and any other means of access to secure accounts,’ she says. ‘Similarly, the procedure needs to extend to third parties, such as contractors or partner organisations. Finally, remind the departing of their legal responsibilities to keep data confidential and dust off their signed acceptable-use policy or other confidentiality agreement.’

There’s very little that can be done about outright falsehoods, though – as SA short-term insurance firm MiWay learned in July, when a snapshot of a racist email supposedly sent from a MiWay employee started doing the rounds on social media.

The creator of the post – and the email – was in fact a former MiWay client. After having a claim legitimately rejected by MiWay and subsequently by the ombudsman for short-term insurance‚ he had used a MiWay email account to create a fake email containing racist remarks and making false allegations about the company’s claims-handling policies. He was subsequently identified in an independent forensic investigation, and issued a statement expressing regret at his actions.

‘He apologised to MiWay for bringing the company into disrepute‚ to MiWay employees‚ especially the two who received hate mail and death threats as a result of his actions‚ and to the people of South Africa‚ for stoking racial tensions‚’ MiWay said in a statement.

However, the full extent of the damage done by this malicious social media attack may never be calculated. Just ask AP. Or HMV. Or Uber.