If R&D and innovation were personified, one would be the scientist – the numbers brain who works long hours in the lab, behind the scenes. The other one would be the ideas person – the creative, cool one, who talks about ‘disruption’ and basks in the spotlight. This simplified, unscientific metaphor – based on Google Trends and subjective interpretation – sees modern ‘innovation’ elbowing traditional ‘research and development’ out of the way.

Across the globe, the focus lies firmly on innovation, considered to be a key driver of economic growth and progress. Name changes reflect this trend; for example, SA’s Department of Science and Technology, was recently rebranded as the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI). And a growing number of companies and academic institutions have been repositioning their R&D departments with the broader concept of ‘R&I’, as in research and innovation.

‘Innovation is potentially a buzzword that companies hide behind to pretend they are doing something differently,’ says Jennifer Sutherland, the co-founder of the Creative Leadership Collective, a peer-to-peer network of innovation leaders in the management consulting industry. ‘There are probably 100 definitions for R&D and especially for innovation, and the challenge is creating a common understanding – whether internally in an organisation or in “public communication”.’

So while R&D and innovation are two different things, they remain intertwined. ‘Yes, they are closely related but can be separate,’ says Sutherland. ‘R&D suggests that the company has taken a direction, and is developing towards that direction, whereas innovation suggests an openness to look for – the activity of looking for – something new and different.’

She describes R&D as ‘quite scientific or technical and typically focused on product – a physical thing – that is based on empirical data and experimentation, typically requiring highly specialised skills. Think about R&D around new pharmaceuticals, machines, information technology, materials. It often happens in isolation’.

On the other hand, says Sutherland, ‘innovation is much broader than R&D, and has many “varieties” – for example, management innovation, business model innovation, service innovation – some of which may require R&D, but not always’.

Awie Vlok, faculty member at Stellenbosch University’s department of business, provides more context: ‘In the knowledge economy the emphasis was on knowledge generation, while the innovation economy emphasises knowledge application, in other words turning knowledge into value through new ideas.’ He suggests teams establish their focus in terms of knowledge generation (R&D) or knowledge application (innovation) to create ‘idea-friendly, idea-hungry environments’.

These are crucial if companies want to future-proof themselves, or even only survive, in this age of exponential increases in scientific and technological advancements. Vlok gives the example of global travel group Thomas Cook, which was listed on both the London and the Frankfurt stock exchanges when it collapsed in September 2019 – an event that adversely affected SA’s travel industry. ‘After 178 years, having survived economically tough times, Thomas Cook ceased to operate,’ he says. ‘They knew that something was wrong and that intervention was needed, so they appointed a PR company to look after their new product development and image – too little and too late to accommodate and capitalise on the disruptive modern-day trends. The average lifespan of companies is shrinking, for similar reasons.’

SA can’t escape the big trends leading to what has been referred to as the Second Machine Age or Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), which according to Vlok will require a paradigmatic change from traditional linear thinking. ‘The choice for South African firms is thus not so much about should they or should they not invest in R&D, but rather be clear on what they want to achieve, understanding that different pathways exist, and to invest in the capabilities to get them to their desired future,’ he says.

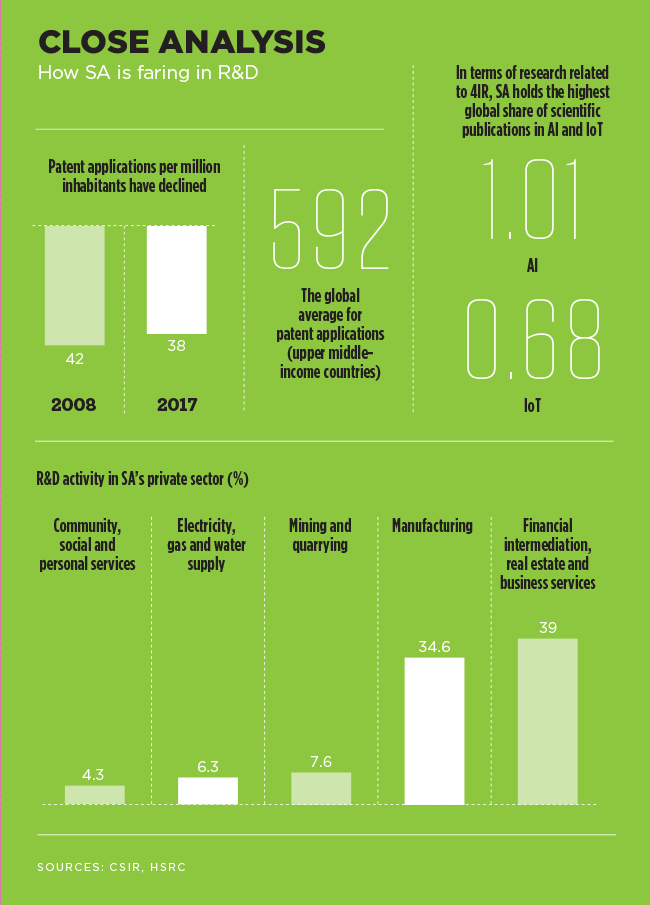

The latest R&D statistics put SA’s gross expenditure on R&D (GERD) at R38.7 billion in 2017/18, which is nominally more (8.5%) than 2016/17. The 2017/18 National Research and Experimental Development Survey (released by the DSI in October 2019) boasts that ‘South Africa’s expenditure on R&D continues to grow’. The official statement clarifies, however, that ‘although this was the seventh consecutive year in which South Africa’s GERD has increased, following a contraction in 2009/10 and 2010/11, the growth in real terms shows a declining trend, especially when compared to the peak of 8.3% reported in 2014/15.’

The survey explains that GERD is an aggregated measure of in-house R&D expenditure performed domestically in the five sectors of government, science councils, higher-education institutions, the business sector, and the not-for-profit sector.

For R&D to thrive, a country requires a pool of qualified, capable research personnel. SA’s ratio of full-time equivalent researchers per 1 000 employed was 1.8 in 2016/17, which is a modest shift from the 1.7 of the previous year. The DSI notes that ‘there is concern over the head counts of technicians and other R&D staff, which have remained constant at around 11 300 and 11 600 respectively since 2012/13. The number of technicians, in particular, needs to expand given the requirements of the Fourth Industrial Revolution’.

SA’s top areas of research are currently not even related to 4IR, according to the DSI. They are infectious diseases, religion, astronomy and astrophysics, plant sciences, and public, environmental and occupational health. However, the country is doing well in terms of gender equality, with the ratio of female to male researchers higher than the global average (44% compared to 38%).

R&D policy analyst Michael Kahn writes in the Daily Maverick that ‘increasing the researcher stock happens in two ways: “growing one’s own” and through immigration. The first is happening slowly; the second is blocked by immigration law. The first is within the span of influence of DSI; the second not’.

Nationally, the business sector remains the largest R&D performer (41% in 2017/18), which is down from 56% in 2006/7, according to the DSI survey. It also notes a change in the composition of business R&D, which has seen ‘robust increases in business expenditure on R&D (BERD) attributed to the services industries, while manufacturing and mining-related R&D has declined. R&D in the financial intermediation, real estate and business services sector now dominates, contributing about 48.8% of BERD in 2017/18. This sector’s R&D spend has surpassed that of the manufacturing sector since 2011/12.’

When analysing and comparing R&D, terminology and context are paramount, according to Vlok. ‘Globally the services sector is showing strong growth, which comes from R&D that is fuelled from the demand side and often not reflected in official R&D numbers, as in the case of manufacturing and technology R&D. It becomes even more complicated when R&D-produced technology is being used to fuel further R&D or innovation.’

He argues that there are various interpretations of R&D expenditure as a ratio of GDP, with the normative view suggesting that ‘South Africa’s investment has been below that of other countries and the portion of private sector investment also lower than what it should or could be’.

SA’s R&D expenditure is hovering around 0.8% of GDP, which is below the 1.5% targeted in the NDP. In comparison, China is currently at 2% and working towards its 2020 goal of spending 2.5% of GDP on research.

Then there is the issue of SA multinationals such as Sasol, Standard Bank and Anglo American (although the London and JSE-listed mining group is considered a British company in the 2019 Forbes list of the world’s largest firms, where it’s ranked 261st). ‘Multinational corporations tend to concentrate some R&D activities in certain areas after which the benefit is shared across their international operations,’ says Vlok.

Sasol invests more than R1 billion annually into R&D (which the group calls research and technology – R&T), including in-house research and development work as well as external (third-party funded) research, according to Vimal Bhimsan, Sasol’s acting senior vice-president for R&T. Although the internal R&T function has reduced the number of employees, it maintains a core capacity of technical expertise, he says.

‘In the past few years, the revised Sasol strategy and a shift away from gas-to-liquids and coal-to-liquids technology development, has resulted in a refocusing of R&T activities. The key focus areas include: sustainability, supporting the transition to a lower-carbon future; energy and process efficiency, optimising existing operations and technologies; new chemical applications and products; and the application of digital technologies to improve our business.’

In 2019, Sasol R&T spent R17 million on 36 university research grants in areas of strategic importance to the group, ranging from innovative catalysis to novel separations to environmental chemistry. Bhimsan points out that ‘such funding becomes more critical to the universities in the face of shrinking government funding’.

Pfano Mashau, lecturer at the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Graduate School of Business and Leadership, would like to see ‘more active interaction and trustful relations’ between universities and big business in order to identify common activities.

‘If academia and industry start working together to achieve a mutual goal, they will share the risks and costs of R&D. Academia and industry are compatible once we realise mutual activities,’ he says. ‘Universities are research institutions, and as such most of the universities’ research breakthrough is not commercialised. To implement research findings, universities need to work closely with industry. Research is costly and so is development. Companies can benefit from working with universities as this relationship might be a solution to the high cost of R&D.’

Nestlé recently set universities and start-ups in SA an R&D innovation challenge to collaborate in bringing breakthrough, scalable science and technology ideas to market. The focus is, among others, on greener packaging solutions and affordable nutrition. The food and drinks giant has been operating in SA for more than 100 years and attributes its sustainable growth partly to ‘reinventing ourselves in these dynamic and evolving times’.

This type of flexibility, combined with an open mind and an understanding of the new science and technology landscapes are some competencies that contribute to innovation outcomes.

Vlok says: ‘Research on successful technology innovation leaders in South Africa revealed that linear sequential processes for innovation are no longer the only norm.’

Or, as Sutherland puts it: ‘Innovation is definitely critical for economic growth but the focus needs to move – in mindset and education – from only R&D-focused innovation to include more disruptive innovation. The former requires a heavy focus on maths and science while the latter comes from the collaboration of multidisciplinary teams, with a variety of skills and backgrounds.’

So metaphorically speaking, ‘innovation’ shouldn’t elbow ‘R&D’ out of the way, but embrace it and provide a modern makeover that combines the numbers brain with the creative one.

The goal should be a more open, dynamic R&D system, where transparency replaces secrecy and ideas are nurtured, enabling the transition from traditional to innovation-directed R&D.