Gavin Kelly was having a bad day. As the CEO of South Africa’s Road Freight Association, he – together with other clients across SA’s logistics industry – had just received a notice from transport parastatal Transnet, advising that it was ‘experiencing a problem with some of [its] IT applications’. That was an understatement. A targeted cyberattack on 22 July had crippled the country’s ports.

‘The gates to ports are closed, which means no trucks are moving in either direction,’ Kelly said in a statement released the next morning. ‘This has an immediate effect – the queues will get a lot longer, deliveries will be delayed and congestion will increase. The manual processes being used are also creating problems in terms of operations. Road freight operators already have a huge backlog resulting from last week’s civil unrest. The delays at the port will further exacerbate the problem. Deliveries will become unreliable and unpredictable – adding further inefficiencies into the supply chain.’

Transnet scrambled for a full week to fix the problem. It shut down its computer systems, instructing staff not to use any laptops, desktops or tablets connected to the Transnet domain, and not to access work emails from their personal devices. On 27 July, Transnet declared force majeure. By then, cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike had revealed that a ransomware note found on Transnet’s systems – linked to the Death Kitty, Hello Kitty and Five Hands ransomware strains – was similar to others it had seen in recent months.

Two months earlier, in May, a ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline had shut down 8 850 km of pipeline along the US’ East Coast. Two months later, in September, SA’s Justice Ministry suffered a ransomware attack that temporarily made it impossible for South Africans to make child-maintenance payments. Also in September, the Australian Cyber Security Centre published a report confirming that recent cyberattacks had specifically targeted critical infrastructure, including healthcare, food distribution, electricity, water and transport. The report warned of ‘significant targeting, both domestically and globally, of essential services’.

The message from cybercriminals is clear: they’re no longer interested in locking you out of your personal laptop; now they’re targeting national infrastructure.

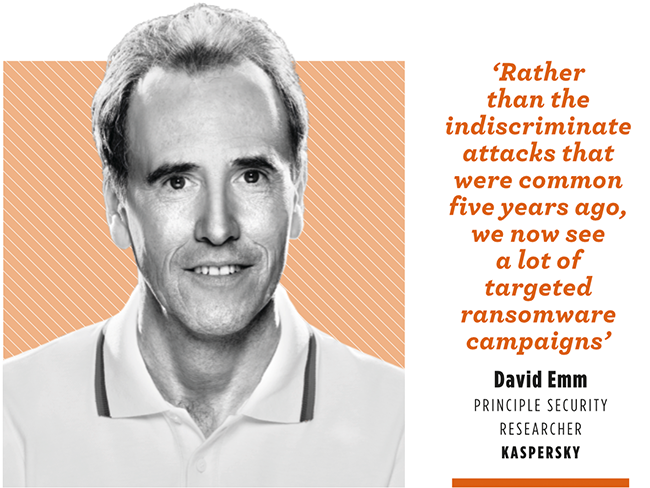

‘In recent years we have seen a change in approach by ransomware gangs,’ says David Emm, principal security researcher at cybersecurity firm Kaspersky. ‘Rather than the indiscriminate attacks that were common five years ago, we now see a lot of targeted ransomware campaigns. The attackers scope out potential victims, focus on “high-return” victims, carry out reconnaissance of their network, identify the high-value resources and only then encrypt the data. In addition, it’s now common for attackers to threaten to publish stolen data as well as encrypt it, to further encourage their victims to pay up.’ Emm says that SA’s cyberthreat landscape is comparable to developed regions such as Europe and North America. ‘In South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria, Kaspersky’s research has identified the top malware families as ransomware, financial/banking trojans, and cryptominer malware,’ he says. ‘And while the bulk of ransomware attacks are still speculative and randomly targeting individuals and businesses, there is a shift happening.’

That shift towards attacks aimed at the government, manufacturing and banking sectors has a simple driver – the high potential for pay-out. Speaking to Security magazine in the US, Stefano De Blasi, a cyberthreat intelligence analyst at Digital Shadows, explains it in the most basic of terms. ‘Cybercriminals’ top priority is simply to get paid at the end of an offensive operation,’ he says. ‘In particular, cybercriminals can monetise more effectively when targeted organisations hold sensitive information and/or cannot afford any downtime due to production needs.’ Such as the Department of Justice’s internal network or Transnet’s national ports system. Capture those, and you can quite literally hold the country to ransom.

No wonder, then, that ransomware has transformed from a mean-spirited form of cyberattack into a lucrative global industry. In fact, ransomware is now being offered ‘as a service’ in some corners of the Dark Web. ‘Most threats, like malware, are relatively easy to deal with,’ says Emm. ‘But Kaspersky is seeing a rise in more professional cybercrime gangs. Our researchers are now monitoring more than 200 cybercrime gangs worldwide who have been launching hyper-targeted attacks against targets such as banks and governments.’

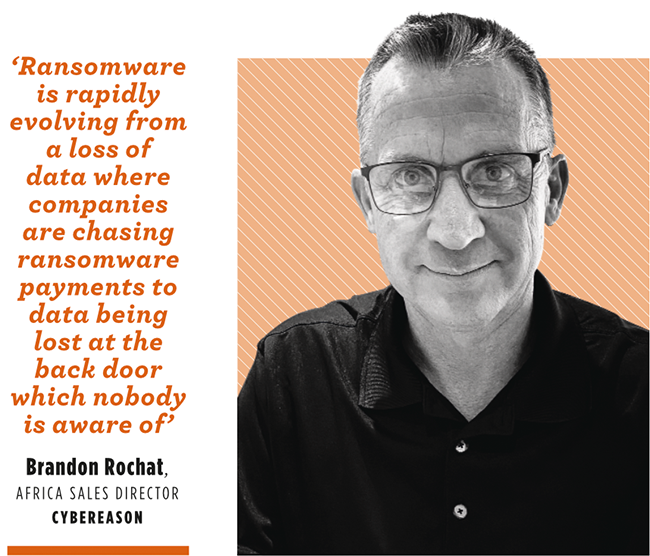

According to Brandon Rochat, Africa sales director at security firm Cybereason, ‘the bad guys, the threat actors, they want to get into your network to deploy a piece of malware that will ultimately encrypt your network and your data. The ransom can be in different formats – money, Bitcoin – and in return, they’ll unlock your data’. (Or not. But more on that later.)

Rochat confirms that there has been ‘a huge increase in ransomware, and all different versions of ransomware’, and he agrees that both the volume and the nature of those attacks have changed. ‘The original ransomware was always around, dropping malware and holding companies to ransom for some kind of financial gain,’ he says. ‘What we’re starting to see is an old military tactic where you make a lot of noise over here, but you go in over there. It’s a deception mode. Ransomware is rapidly evolving from a loss of data where companies are chasing ransomware payments in the form of bitcoin, for example, to data being lost at the back door which nobody is aware of.’ Rochat says that there are basic things organisations can do to protect themselves against ransomware attacks, but he warns that ‘it’s often the simple things you don’t do that open the doors. Get a good password system going, use two-factor authentication, keep control of your software updates and be involved with organisations that defend you against ransomware. Even when you’ve done the basics, you still need another layer on top of that’.

In the UK, the National Cyber Security Centre’s (NCSC) technical lead for incident management – who is known only as ‘Toby L’ (because what we’re talking about here truly is the stuff of TV drama) – recently shared a cautionary tale for organisations that respond to cyberattacks without addressing their underlying causes. ‘We’ve heard of one organisation that paid a ransom (a little under £6.5 million with today’s exchange rates) and recovered their files (using the supplied decryptor), without any effort to identify the root cause and secure their network,’ Toby L writes on the NCSC website. ‘Less than two weeks later, the same attacker attacked the victim’s network again, using the same mechanism as before, and re-deployed their ransomware. The victim felt they had no other option but to pay the ransom again.’

Stories like that make Kurtis Minder want to pull his hair out. Minder is CEO of cybersecurity company GroupSense, and is regarded as one of the US’s top ransomware negotiators. In an op-ed piece for the Baltimore Sun, Minder rails against organisations that fail to adequately protect themselves against ransomware attacks. ‘I’ll put it bluntly,’ he writes. ‘The bad guys are not using very sophisticated techniques in their attacks. In fact, they’re using the same old tricks they’ve used for a long time. Only instead of just stealing data (remember those “good old days”?), they’re breaking into corporate networks and unleashing ransomware.’

Minder dismisses the popular advice about not paying the ransom (‘If you’re a small business that will go under in a few days if you can’t get your systems back online, that kind of blanket guidance isn’t really useful or practical,’ he says); while taking a stab at organisations that fail at what he describes as simple cyber hygiene. ‘What bothers me most is how preventable this all is.’

He has a point. Kaspersky’s Emm suggests a few basic protective measures – all of which would fall under the umbrella of Minder’s cyber hygiene. ‘Always keep software updated on all the devices the company uses to prevent ransomware from exploiting vulnerabilities,’ he says. ‘Focus the defence strategy on detecting lateral movements and data exfiltration to the internet. Pay special attention to outgoing traffic to detect cybercriminal connections. ‘Back up data regularly, and make sure the business can quickly access it in an emergency when needed. Carry out a cybersecurity audit of all corporate networks and remediate any weaknesses discovered in the perimeter or inside the network. Explain to all employees that ransomware can easily target them through a phishing email, a shady website or cracked software downloaded from unofficial sources.’

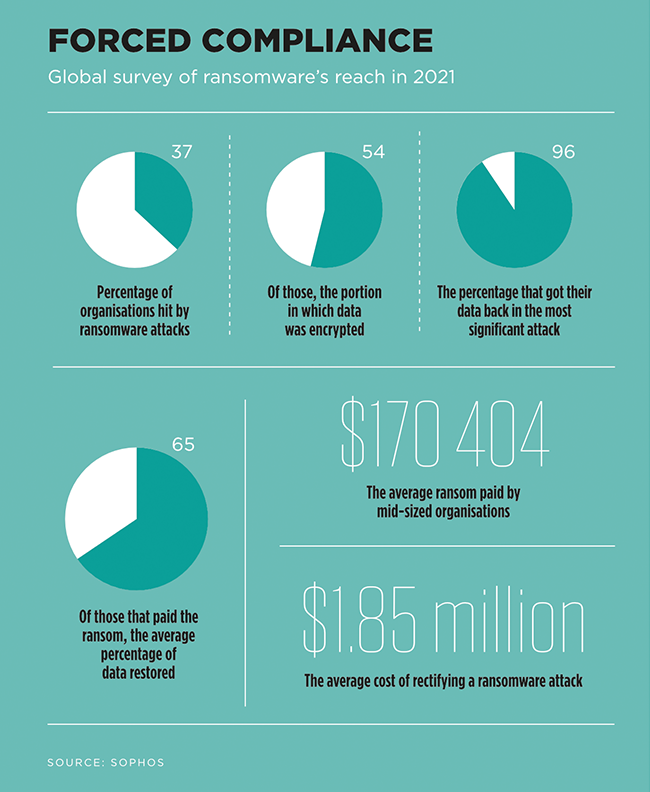

As for paying the ransom… Kaspersky’s research indicates that if you’re receiving a ransomware notification, you’ve already lost. Emm points to findings that just 24% of ransomware victims in SA were able to restore all their encrypted or blocked files following an attack – whether the victims paid the ransom or not. Paying extortionate ransoms, he says, ‘only encourages cybercriminals to continue their practice. Instead, law enforcement must be involved as early as possible’.

Emm adds that organisations or public sector entities that fall victim to a ransomware attack, should stay calm and look for a decryptor. ‘They should also talk to the vendor they purchased their protection system from,’ he says. ‘First, find out how it happened that the data was encrypted. Second, ask the vendor for help with the decryption: it might be that the vendor knows what to do, and they probably will want to help a valued customer.’ But Emm – like Minder and Rochat and any other cybersecurity pro you speak to – emphasises that prevention remains better than a one-in-four shot at a cure.

‘It is always better to strengthen cyber defences to be able to prevent infections in the first place,’ he says. ‘If everyone stops paying, the extortionists will gradually end their racket, and the world will be able to breathe a little easier.’