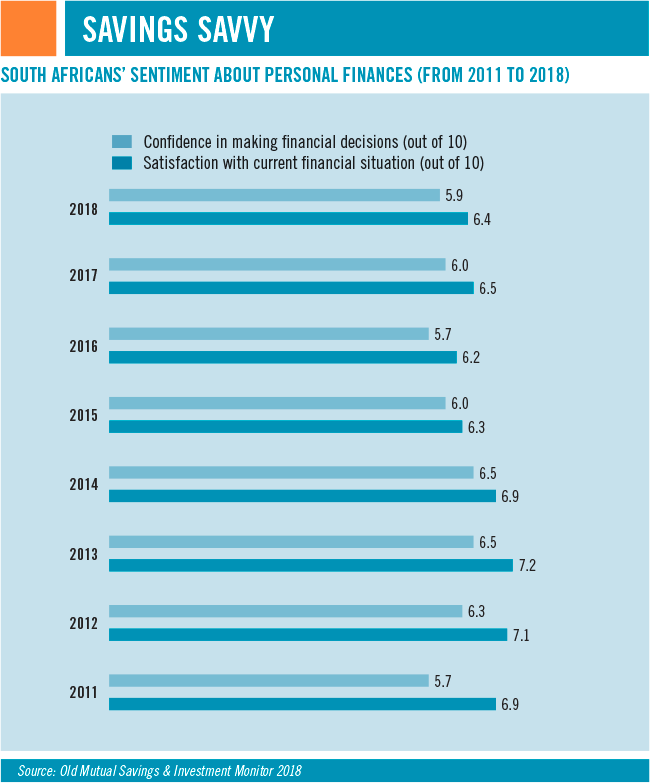

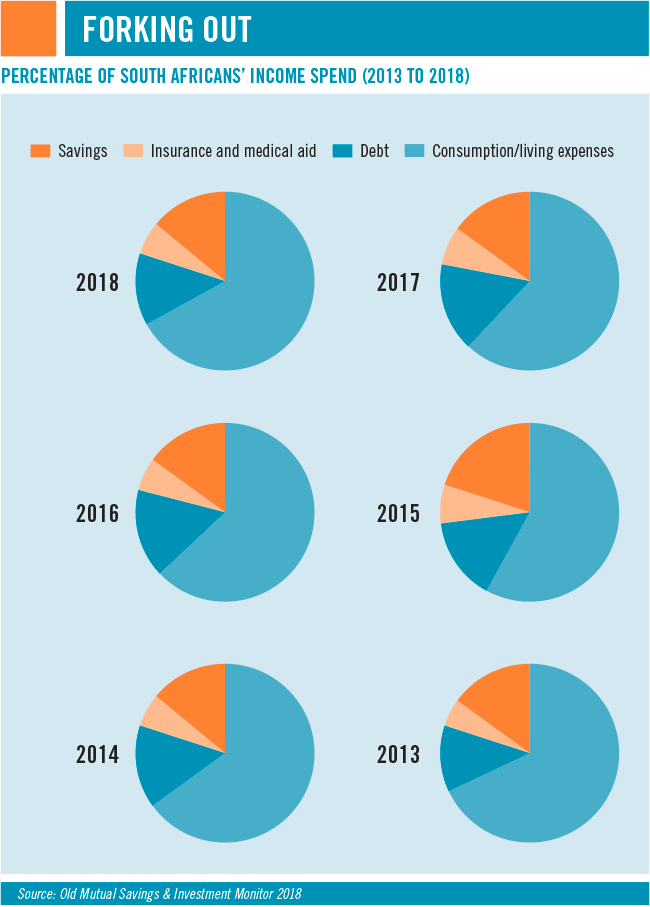

Here are the blunt facts: South Africans save too little and start too late. Our average savings rate is 7% compared to the suggested minimum of 15%, and we only start saving aged 28 years as opposed to the suggested 23 years, according to the 2018 Sanlam Benchmark Survey. Study after study shows that we are a consumerist nation with too many people in debt or living beyond their means. SA’s household savings rate comes last when ranked against the G20 countries, according to a survey by fintech startup MyTreasury.

‘Saving is a learned behaviour,’ says Adrian Saville, chief executive at Cannon Asset Managers and professor in economics, finance and strategy at Pretoria University’s Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS). He is the co-author of the annual Investec-GIBS Savings Index, which shows that SA’s resistance to saving reached a historical low at the end of 2017, having declined for seven consecutive years.

Saville has talked about the country’s lack of financial literacy and cautioned that the only way to prosperity is by saving, not spending. Asked about SA’s savings behaviour, he says: ‘It is ironic that I am replying to you on Black Friday, which is a day devoted to urging people to spend.’

Financial industry initiatives promoting the opposite – urging people to spend prudently and plan for their financial future – often go unheard. That’s where behavioural economics may come in useful. In March, SA will see the launch of ‘the world’s first and only behavioural bank’. At least that is how the new Discovery Bank is marketing itself – as a bank that ‘motivates and rewards you for banking well’, thereby creating a virtuous financial circle.

‘The purpose of the bank is to make people healthier in the financial sense,’ Discovery group CEO Adrian Gore said at the pre-launch in November. ‘Banks don’t acknowledge people that do manage their money well. The stats are terrible: 5% to 10% of people are expected to retire satisfactorily – that means 90% won’t. There are more people credit-active than formally employed. Forty percent have no retirement plan whatsoever.’

Discovery Bank wants to change this by offering customers financial education, budgeting advice and access to debt managers and retirement planners (as SA’s leading banks already provide), but what sets the new offering apart is its dynamic interest rates on savings and loans. This ‘democratisation’ means that risk is assessed on the customer’s financial behaviour, irrespective of salary size and whether they are formally employed. Therefore low-income earners or the self-employed who manage their money responsibly will be charged more competitive interest rates than higher-income earners who aren’t managing their money prudently.

‘What’s good for us is good for our customers, but, fundamentally, it’s good for society,’ says Gore, who presents the ‘Vitality Money’ strategy as a logical extension of the behaviour changes achieved through the group’s insurance, health and investment businesses.

Old Mutual also introduced a rewards-based loyalty programme (in mid-2018), allocating rewards points for customers who complete financial assessments, use online calculators for education savings or debt repayment, and complete online education modules.

‘We believe that by encouraging certain behaviours, we will shift mindsets from consumerism to responsible planning and wealth creation,’ according to Jean Minnaar, general manager of product solutions at Old Mutual. ‘Among the behaviours we particularly hope to encourage are effective day-to-day money management, financial knowledge-seeking to support sound financial decision-making, gaining insight into your own financial needs, financial planning and goal setting. But most importantly, following through on financial decisions.’

It’s too early to say whether these initiatives will yield the desired outcomes. But Saville seems enthusiastic in principle. ‘Behavioural banking has a prospect of having a positive effect. From experiences elsewhere, including developed and emerging markets, and at various income levels, there is a range of ways in which behaviour can be nudged to promote higher savings rates,’ he says. ‘For instance, behavioural inertia allows you to link “good outcomes” to “bad habits”. We are involved with such a tool at Bidvest Bank, where a savings pocket has been linked to spending, with the option to send X% of spending on each trans-action into a savings pocket, that can then be tipped to an investment.

‘Setting visual goals or concrete goals is a positive nudge. Rather than “save X%”, you could set a visual goal such as “save for a year of your retirement; save for this flat screen” and similar. You can also nudge by negative signals – for instance, if you save X%, your retirement will be in poverty and you will live in this house and afford zero holidays.’

There is, of course, a fine balance between what motivates one person and possibly repels another. Millennials, for example, don’t like fear tactics or being told what to do, says Karishma Ramkelawam, consultant at Simeka Consultants and Actuaries. Her research for Sanlam’s 2018 Benchmark Survey indicates that millennials (defined as 22- to 37-year-olds who make up 40% of SA’s workforce) require new communication tactics, conveniently packaged in the form of ‘infographics, snackable content and videos’.

She advises the retirement fund industry to critically re-evaluate the way it communicates with younger members. ‘Even just including the word “retirement” on the invitation or agenda will immediately disengage millennial invitees due to the strong negative emotions invoked,’ writes Ramkelawam. ‘An alternative would be to focus on very specific issues to be able to educate in an influential manner. For instance, using internet click-bait tactics to generate interest (“Staff member makes millions: find out how!”). Also, the individuals conducting sessions need to be relatable and credible. Millennials don’t want to be spoken down to.’

Sanlam’s financial education campaigns take these learnings into account. In 2017, there was the award-winning social media soapie Uk’shona Kwelanga, which created dramatic interest for the sober topic of funeral cover – entirely played out on WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. Next came an interactive audio drama, Lives of Grace, in which subscribers were able to influence the storyline.

In 2018, Sanlam’s ‘Conversations with Yourself’ campaign encouraged people to think how their present actions would affect their financial future in six different life stages. It’s a highly engaging way to tackle ‘boring’ finance topics (financial planning, life insurance, life insurance, pre- and post-retirement planning, savings, investment and disability cover).

‘The simple act of creating “chatter” – such as social media chatter – tilts behaviour,’ says Saville. ‘Interestingly, the behavioural nudges do not care about geography or income level. They do care about gender and age, though.’

Old Mutual’s Moneyversity is also geared at creating social media chatter and putting ‘fun’ into online financial education. It uses videos, games, infographics, calculators and articles to get the message across, and is the online platform for the firm’s rewards-based loyalty programme.

The Association for Savings and Investment South Africa (ASISA), which represents Old Mutual and other collective investment scheme management companies and service providers, asset managers and life insurance firms, has also realised the value of social media. The association has been extending its reach to bring financial consumer education to different levels of society. ‘Our view is that one needs to save money to invest and not to consume,’ says ASISA CEO Leon Campher. ‘In the less advantaged levels of society there’s a reasonable savings culture via stokvels, but it’s consumption-driven and could significantly increase its impact through a more structured and formalised approach.’

The ASISA Foundation is educating collective savings groups on investment vehicles such as money market accounts, unit trusts or the stock exchange. In addition, the foundation’s Saver Waya Waya Financial Literacy Programme has prepared 1 000 final-year TVET college students from disadvantaged communities in Gauteng for the workplace and for managing their money once they start earning an income. At the end of the training, the students performed their own drama pieces in an awards ceremony to demonstrate their understanding of the learning materials and share their newly acquired skills with their peers.

Programmes to promote financial education and personal saving have benefits that go well beyond individual wealth creation. ‘A savings culture is important to ensure enough capital for investment in the economy. Investment is the driver of future economic growth,’ says Jannie Rossouw, head of the Wits School of Economic and Business Sciences.

‘Naturally we cannot expect people who live from hand to mouth to save. When the need to save is mentioned, we have to look at government, [which] should not use borrowed funds for current expenditure; companies, [which] should make sufficient provision for wear and tear and depreciation, thus preserving capital for future investment; and households that have discretionary income.’

He stresses the importance of households refraining from withdrawing their pension savings when changing jobs. Campher agrees. ‘Provident funds are favoured over pension funds, so when people leave their company they tend to take their cash with them. Furthermore, there’s no auto-enrolment, so even those in formal employment often don’t have access to a retirement fund.’

Wealth preservation for retirement is a big challenge in SA, with one out of three baby boomers (those born before 1965) having no formal retirement provision, according to the Old Mutual Savings and Investment Monitor. Thirty-eight percent of respondents expect to depend on their children in retirement and 32% want government to provide for them.

Government, too, is trying to improve the saving culture through tax-free savings accounts and tax incentives for retirement and education savings. Successful public-private partnerships include the Fundisa Education Unit Trust (ASISA; Department of Higher Education and Training; National Student Financial Aid Scheme), which boosts the benefits of beneficiaries by 25% to a maximum of R600 per learner a year. There are also calls to include financial literacy in the school curriculum, starting at primary school level.

The problem is well recognised and well articulated. As a nation we need to save and invest more and disruptive technology, online tools and financial institutions are doing their bit. Now it’s over to us, with a helping hand from government, to do ours.