When Ketso Gordhan, former CEO of cement producer PPC, announced his sudden resignation in September 2014 over disagreements with the board, the company’s corporate governance battles made news headlines for weeks. Mining exec Darryll Castle, a non-executive on the PPC board at the time, was announced Gordhan’s successor less than three months later but the leadership uncertainty hurt investor confidence and dented the company’s share price, which lost a quarter of its value between September and December.

In contrast, almost a full year before his resignation, the market was alerted that Sanlam’s Johan van Zyl would be resigning as CEO of one of the continent’s largest insurers. At the same time, Ian Kirk, CEO of the group’s short-term insurer, Santam was appointed deputy group chief executive with a view to take over the top position.

Clearly, Sanlam had a firm CEO succession plan in place, further indicated by the fact that Sanlam’s head of personal finance, Lizé Lambrechts, was later appointed CEO of Santam.

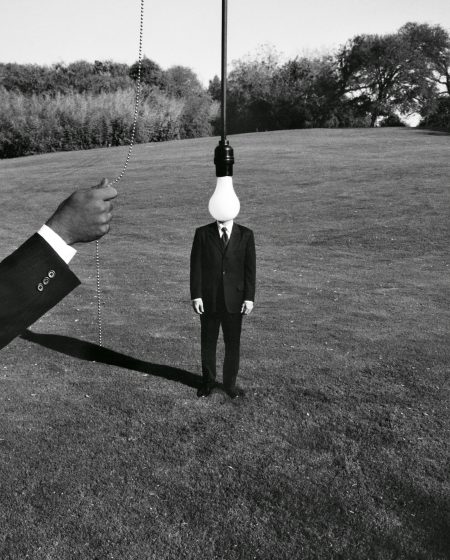

In terms of the King III codes regarding corporate governance, succession planning for the chairperson and CEO are the responsibility of the board. Richard Foster, an independent corporate governance advisor and former chairperson of the Institute of Directors in Southern Africa, says that his overall impression is that CEO succession planning is still ‘somewhat of a mixed bag, where certain companies appear to have a plan in place, whereas others have had to implement crisis mode’.

This problem is not unique to SA. According to a 2014 survey conducted by the US’ National Association of Corporate Directors, two-thirds of private and public companies in the country have no formal CEO succession plan in place.

Foster highlights that the board should cater for the planned, as well as the possible unplanned, departure of a CEO and ensure attendant risks are suitably mitigated.

‘CEO succession planning is a critical process that many companies either neglect or get wrong. While choosing a CEO is unambiguously the board’s responsibility, the incumbent CEO has a critical leadership role to play in preparing and developing candidates – just as any manager worth his or her salt will worry about grooming a successor,’ according to a McKinsey Quarterly article written by Åsa Björnberg and Claudio Feser, senior expert and director respectively at the global management consulting firm.

The authors highlight that CEO succession planning should be a part of a firm’s broader system of leadership development and talent management. Treating CEO succession in a reactionary manner, triggered by the departure of the old CEO, poses significant risks.

The authors highlight that CEO succession planning should be a part of a firm’s broader system of leadership development and talent management. Treating CEO succession in a reactionary manner, triggered by the departure of the old CEO, poses significant risks.

‘Potentially good candidates may not have sufficient time or encouragement to work on areas for improvement, unpolished talent could be overlooked, and companies may gain a damaging reputation for not developing their management ranks,’ write Björnberg and Feser. ‘Ideally, succession planning should be a multi-year structured process tied to leadership development. The CEO succession then becomes the result of initiatives that actively develop potential candidates.’

One way of actively developing potential candidates is by getting them to take up certain key leadership positions in the company and testing their mettle on that basis.

For example, the McKinsey article points out that the chairman of one Asian company appointed three potential CEOs to the position of co-chief operating officer and rotated them every two years through leadership roles in sales, operations and research and development.

Executive search consultancy Russell Reynolds Associates points out that in addition to the critical importance of maintaining the confidence and goodwill of shareholders, investors, employees and other company stakeholders, effective succession planning also helps drive senior executive development in such a way that aligns the skills and talent of top leadership with the strategic needs of a firm in an ever-changing world.

Fay Voysey-Smit, managing partner at executive recruitment firm Boyden, agrees that CEO succession planning must relate to company strategy.

‘Strategic direction has to keep pace with changing business and operating environments and shifts in economic climate. This is often not reflected in the CEO search. Organisations may simply appoint an internal executive, who was perhaps earmarked for the role some time previously, but whose skills do not fully reflect the changing needs of the business,’ she says.

Once a firm is clear on what their future strategic direction is and what sorts of capabilities it needs to successfully pursue such a strategy, Russell Reynolds Associates CEO Clarke Murphy recommends that it should then compare these capabilities against its own senior talent pipeline. ‘Boards can decide to bolster this talent pipeline by recruiting from the outside,’ he says, according to the company’s website.

This is exactly what happened in the case of Old Mutual, which earlier this year surprised the market with the news that its CEO, Julian Roberts was stepping down and would be replaced by Standard Bank executive and former Liberty head, Bruce Hemphill. Quite simply, Old Mutual didn’t feel that anyone within its own ranks offered the same skill set as Hemphill: a combination of insurance, banking and wealth management knowledge, coupled with experience in growing businesses into Africa and forming a successful bancassurance partnership between Liberty and Standard Bank – something it appears Old Mutual wants with Nedbank.

‘Potential internal successors should be benchmarked against the most relevant and appropriate external executives. This will ensure that the most appropriate individual with the highest level of strategic and operational capability and skills is appointed into the role to deliver shareholder value,’ says Voysey-Smit.

According to Björnberg and Feser, three broad criteria can help companies evaluate potential candidates: know-how, such as technical knowledge and industry experience; leadership skills, including the ability to execute strategies and manage others; and personal attributes, such as personality traits and values.

‘These criteria should be tailored to the strategic, industry, and organisational require-ments of the business on, say, a five- to eight-year view,’ they argue, adding that as a company’s strategy changes, so too might the mandate of the CEO, requiring differing types of leadership skills.

‘Strategic direction has to keep pace with changing business environments and shifts in economic climate’

FAY VOYSEY-SMIT, MANAGING PARTNER, BOYDEN

‘For example, the leadership style of a CEO in a media business emphasised a robust approach to cost cutting and fire-fighting through the economic crisis. His successor faced a significantly different situation requiring very different skills, since profitability was up and a changed economic context demanded a compelling vision for sustained growth,’ they say.

The authors underline the importance of de-personalising the process by institutionalising it, so as to remove any selection biases that may creep in.

For example, the ‘more of me’ bias, where CEOs look for a replica of themselves; the sabotage bias, where CEOs undermine the process by promoting someone who may not be ready for the top job; and the herding bias, where members of a selection committee consciously or unconsciously adopt the views of the incumbent head of the board.

While not primarily responsible for selecting a new leader, the incumbent CEO should be primarily responsible for developing that individual, say Björnberg and Feser.

‘The incumbent’s powerful understanding of the company’s strategy and its implications for the mandate of the successor (what stakeholder expectations to manage, as well as what to deliver, when, and to what standard) creates a unique role for him or her in developing that successor,’ they say.

‘I think the main thing that companies can do to prepare themselves for CEO succession is to not treat it as an event, but to treat it more as a process, something that happens all the time at board level and is communicated as such,’ says Ken Favaro, senior partner at PwC’s global consulting team, Strategy&.

‘The second thing I would recommend is that boards think two CEOs ahead, not just one. By the time you’re in the window of thinking who the next CEO is going to be, your options have already narrowed considerably.’