It all started with a troop of monkeys. In July 2011, British photographer David Slater travelled to Indonesia to photograph the local wildlife. He encountered a troop of macaques but found that they were too shy for close-ups – so he set his camera up on a tripod and stepped back. One of the monkeys – a particularly curious fellow later named Naruto – clicked the button and took a selfie.

The photograph was the perfect combination of unusual, amusing and infinitely shareable. It didn’t take long for Naruto’s beaming grin to go viral. Then in 2014, Wikipedia posted the ‘monkey selfie’ and, figuring that a monkey took the photo and monkeys can’t own copyright, they tagged it as being in the public domain.

Slater disagreed, and a copyright dispute ensued. In 2015 animal rights group People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) sued Slater on Naruto’s behalf, telling a California court that the image had ‘resulted from a series of purposeful and voluntary actions by Naruto, unaided by Mr Slater, resulting in original works of authorship not by Mr Slater, but by Naruto’. A provisional ruling found in favour of Slater. PETA appealed and, in 2018, lost – but by then Slater and PETA had already settled out of court.

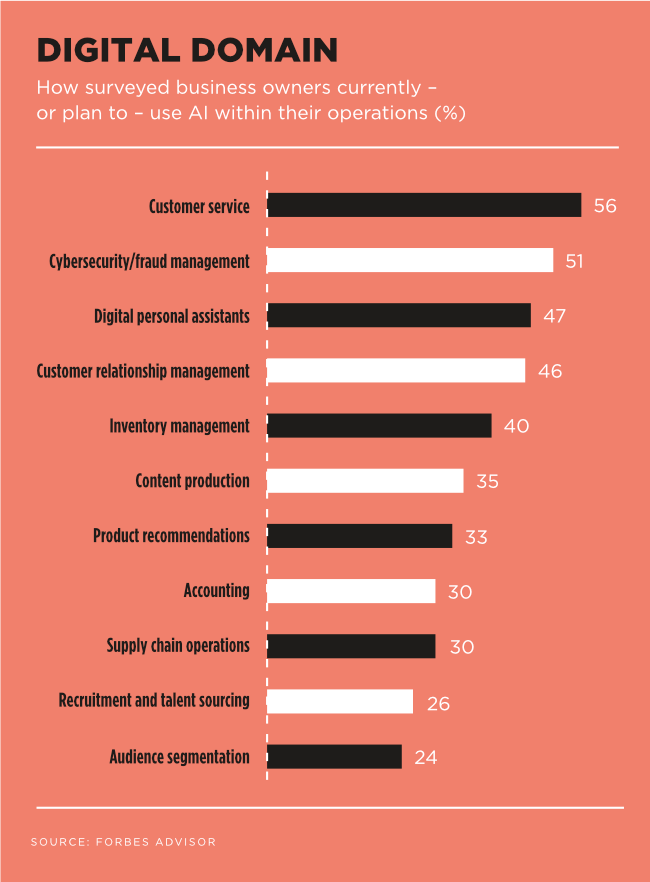

Bottom line – if you’re not a human (sorry, Naruto), you cannot hold copyright under US law. And the matter seemed to have ended there, consigned forever to the realms of pub quizzes and law school textbooks … until AI entered the room. While generative tools such as ChatGPT (for text), Speechify (text-to-speech), Wordtune (spellchecking) and DALL.E (images) have been attracting most of the headlines, AI is becoming ubiquitous. From smartphones to smart homes, e-commerce recommendation algorithms and AI-based application programming interfaces (APIs), it is in the background of a vast array of business systems and processes.

‘AI is everywhere,’ says Nick Bradshaw, founder of the South African Artificial Intelligence Association (SAAIA). ‘In our State of AI in Africa report, we found that AI and its related automation technologies are currently impacting more than traditional industries. It is impacting every industry vertical.’

Which brings us back to the grinning monkeys. If Naruto the macaque can’t own his selfie, then who holds the copyright of content – be it a blog post, artwork or business process – that’s designed and created by a machine?

In 2021 Stephen Thaler thought he had the answer. In a landmark case, the South African Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) became the first patent office in the world to grant a patent that named an AI (and not a human) as the inventor. While Thaler was the patentee, the patent listed Dabus – that’s ‘Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience’ – as the brains behind a mechanism that interlocks food containers based on fractal geometry.

That was the ruling… But technically, the ruling was wrong. Thaler had filed similar patent applications elsewhere – including the US, EU, UK, Taiwan, India, Israel, Australia and pretty much any jurisdiction that would hear his case – and all were rejected on the basis that Dabus was not a natural person.

As several lawyers pointed out, the CIPC should have done the same. That’s because while SA’s amended Copyright Act (Act 98 of 1978) provides that non-humans – including computers and, presumably, Indonesian monkeys – may hold a copyright, the Patents Act does not. So while you cannot legally copy an AI invention, AI cannot legally invent anything either.

In some cases, copyright holders are doing the testing. Visual media company Getty Images recently filed a suit in the US against Stability AI, the creators of open-source AI art generator Stable Diffusion, claiming that it ‘unlawfully copied and processed millions of images protected by copyright and the associated metadata owned or represented by Getty Images absent a licence to benefit Stability AI’s commercial interests and to the detriment of the content creators’. In other words, Stability AI stands accused of illegally copying more than 12 million images from the Getty Images database and using those copyrighted images to train its AI tools.

Generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT and Stable Diffusion, ‘learn’ how to create content by drawing on a vast library of data. Getty Images contends that Stable Diffusion built its dataset using Getty Images’ work, without permission or payment. It doesn’t help Stable Diffusion’s case that its software has a strange habit of recreating the famous Getty Images watermark in many of its AI-generated images.

‘The way that ChatGPT generates written content could potentially infringe upon the copyright of existing works, particularly since [its owner] OpenAI does not obtain consents or licences from the owners of copyrighted works that it mines for information,’ says Carla Collett, an intellectual property specialist at law firm Webber Wentzel. ‘Under South African law, copyright infringement could occur if ChatGPT generates content that amounts to a reproduction or an adaptation of existing copyrighted material. This raises an interesting question: whether the users of ChatGPT, in addition to OpenAI, could be liable for damages when their reproduction or adaptation – or further exploitation – of the copyrighted work falls outside the ambit of the “fair dealing” defence.’

To be clear, Getty Images claims that it has no problem with AI as a technology. The company emphasises that it ‘believes artificial intelligence has the potential to stimulate creative endeavours’. Its complaint is based on copyright infringement. As Getty Images CEO Craig Peters told the Verge, ‘I equate [this to] Napster and Spotify. Spotify negotiated with intellectual property rights holders – labels and artists – to create a service.’ Napster, infamously, did not.

For businesses, there’s a risk aspect to all of this as well. If AI designs your business process (or a portion thereof), who owns that process? Is it the person (and remember, in many jurisdictions it has to be a person) who told the AI what to create? Is it the person who created what the AI learnt from in the first place? Or is it the person who owns the AI platform?

In the case of popular platforms, there are no blanket answers. ‘Interestingly, the owners of these AI services themselves haven’t yet come to a firm conclusion on the question,’ Thomas Schmidt, an associate at law firm Kisch IP, writes in a recent opinion piece. And he’s right – Midjourney says that they own anything you create with their platform (unless you’re a paid subscriber); while ChatGPT and Stable Diffusion say you own whatever you create on theirs (which means that students who use ChatGPT to write their homework are merely cheats and not copyright infringers).

‘In this rather confused environment, anyone who wants to use a generative AI service would be well advised to hunt down and read the associated terms and conditions,’ Schmidt writes, with admirable restraint.

Fatima Ameer-Mia, a director at law firm Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, has another take. ‘If the machine is truly autonomous, the work is technically “original” – and not commissioned – as the work would be machine-learned from a series of data inputs,’ she says.

‘In some instances, the company and/or person feeding the data (inputs) may not know what the output will be – work could therefore be an incidental creation. However, in other instances the work may be “commissioned” and the copyright vests with the person who commissions such work.’

‘AI copyright law is an emerging field,’ says Bradshaw. ‘There are no global standards and policies, and we are in a very transitional phase. We’re in an interesting space here, where multiple segments of laws apply and it’s all up for debate. Much of this is new and has never been tested or is currently being tested.’

Collett agrees. ‘The more this technology is refined, rolled out and used by individuals and organisations across the globe, the more important it is to flag the evolving copyright-related considerations, as they are not clear-cut,’ she says. ‘The South African Copyright Act, which is now 45 years old, certainly did not contemplate artificial intelligence technologies when it was drafted.

‘Even though there are proposed amendments to the Copyright Act which should, in theory, bring the law into the 21st century, it will be interesting to see how the legislation, courts and organisations will balance the multitude of competing rights.’

In the meantime, the legal waters around modern copyright remain murky – whether you’re a machine, a business manager or a selfie-taking macaque.