Andri du Plessis and Nic Janeke wanted to open a micro distillery, selling small batches of craft spirits from their tasting room in Cape Town’s trendy Woodstock precinct. Du Plessis is a creative with a flair for marketing; Janeke is a master distiller who studied chemical engineering. They had almost everything they needed to get their small business up and running: location, skills, determination and a thirsty market. They even had a name – New Harbour Distillery.

Like so many SMEs, however, they lacked start-up capital. ‘The truth is, there are very few tools to start companies like ours,’ says Du Plessis. ‘If you don’t have existing funds or an investor to help you out, it’s very hard to get a loan.’ Determined to get the business going but frustrated by what Du Plessis called ‘a rocky road’ to securing traditional financing, Janeke and Du Plessis turned to crowdfunding.

The crowdfunding model is quite simple. A project creator (such as New Harbour Distillery, for example) proposes a venture to be funded. Backers then support that venture through a moderating platform (such as Kickstarter in the US, or Thundafund in SA), which brings the two parties together.

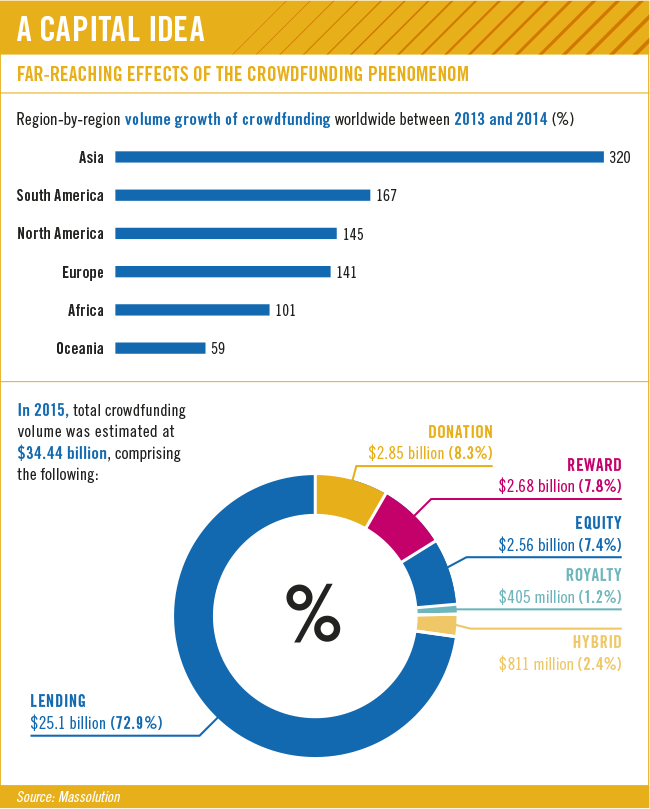

The crowdfunding market has grown at a remarkable pace, and it’s set to explode in the near future. According to research firm Massolution, crowdfunding platforms raised $16.2 billion worldwide in 2014 – up 167% on the $6.1 billion raised in 2013. It also predicted that the global crowdfunding market would hit $34.44 billion in 2015.

According to the World Bank, crowdfunding may well reach $90 billion by 2020. Massolution sees it reaching that figure by 2017. To put that into perspective, Forbes claims that venture capital (VC) averages ‘roughly $30 billion per year and in 2014 accounted for roughly $45 billion in investment, whereas angel investor capital averages roughly $20 billion per year invested’.

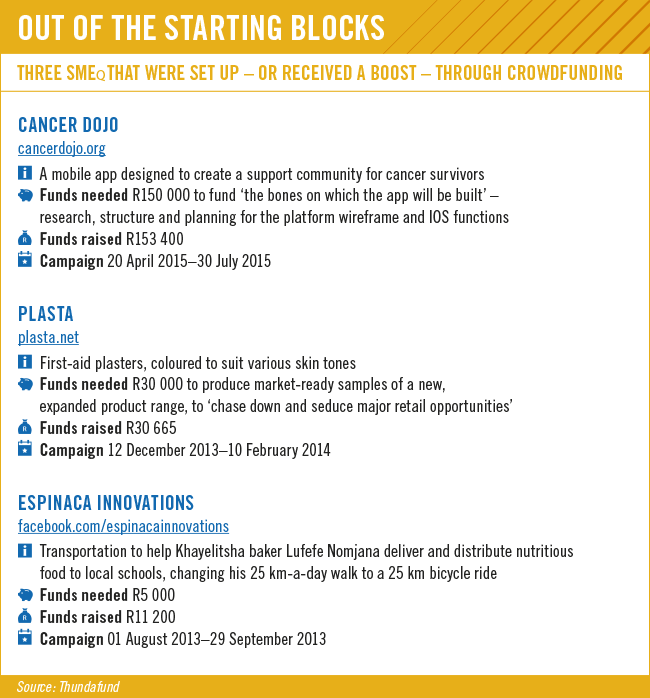

Thundafund only launched in SA in 2013, yet by the first week of 2016 it had already raised R6 million for 167 listed projects. ‘Kickstarter’s third year equalled the accumulative amount of their first two years. Thundafund is seeing almost the same type of growth as we head into our third year,’ according to Winslow Schalkwyk, Thundafund’s community and marketing manager.

‘Although, in our experience, the South African market is still getting used to – or trusting – online purchasing and the concept of rewards-based crowdfunding.’

Kickstarter in the US acts solely as a funding platform: once the project is launched, its work is done. In SA, Thundafund is far more hands-on.

‘We understand that crowdfunding is still new to Africa, so we’ve developed crowdfunding education tools that aid us in teaching backers and potential crowdfunders about crowdfunding.

‘We offer support in marketing and developing a business plan for your innovation or project, and in getting a crowdfunding campaign online,’ says Schalkwyk.

As part of that support, Thundafund allows project creators to set up funding milestones.

Again, New Harbour Distillery provides a useful case study. Launched in October 2015, their ultimate funding goal was R120 000. Along the way they had two milestones: R60 000 (the minimum to launch the project, which was realised in January 2016) and R80 000 (to expand their premises), which they are well on track to meet.

Part of Thundafund’s model is based on its rewards system, whereby project creators reward backers for their financial contributions by offering them project-related items. For example, if you pledge R250 to New Harbour Distillery’s campaign, they’ll reward you with a specially packaged bottle of their rooibos-infused gin.

‘Rewards-based crowdfunding offers backers incentives for their monetary support. This allows the campaign creator to pre-sell merchandise and to conduct market research on the product that they want to put on the market,’ says Schalkwyk.

‘They can gauge whether their product has any market value. No other model exists where you can gather this sort of information while gaining seed capital as well, without having to incur astronomic costs or by placing yourself, as an SME, in debt.’

Another SA crowdfunder is Different.org – a division of Different Life Insurance – which facilitates fundraising for charitable causes run by credible NGOs. Different.org’s operations manager Ryan Sobey points out that not just any charity gets to participate. ‘Donors need to know they are making a credible impact on a charity that is genuinely making a difference to lives. We look for projects that fall into one of five major categories.

‘Our focus areas for philanthropy are: poverty alleviation; job creation; healthcare; education and the environment.’ Here, the backers are donors who receive no tangible rewards or equity stakes.

It’s all very nice receiving a bottle of gin by way of thanks for a small donation, for example, but what about investors who want a more tangible return on investment? Here, the local market still has some limitations.

‘Thundafund is in the “pre-tail” market,’ says Schalkwyk. ‘It’s a hybrid between a donations, investment and retail market. Backers of projects get a benefit in return – that benefit being recognition, products or access. Hence your money is often still “at risk”, as the product is yet to be created, but you are getting something in return – though not in capital.’

At this stage, Thundafund does not allow for equity or shares to be sold as a reward. ‘We are in discussions with a VC partner to launch an associated platform specifically for equity crowdfunding exclusively, using our existing technology back-end as a base,’ says Schalkwyk.

‘Equity- and investment-based crowdfunding are presently being discussed between the African Crowdfunding Association [ACfA], Thundafund and the Financial Services Board, with the objective to develop a regulatory framework that will facilitate equity crowdfunding.’

In January this year, the US Securities and Exchange Commission introduced new guidelines on how startups can sell equity via crowdfunding. In December, the ACfA was launched to lobby for similar legislation in Africa – driven by the understanding that what works in the US will not necessarily work in Africa.

‘We see crowdfunding as the democratisation of financing for entrepreneurs,’ Patrick Schofield, Thundafund CEO and one of the drivers of the ACfA, said at its launch. ‘Thus far we have been thrilled to see the outpouring of African and global support for African entrepreneurs that have had the courage to launch new ideas into the world. There are so many inspiring entrepreneurs in Africa who could do so much to change the world with access to capital. Crowdfunding is the next-gen solution to Africa’s development agenda.’

Taking a closer look at Massolution’s numbers, rewards-based crowdfunding would form 7.8% of the overall market in 2015 – roughly the same as equity crowdfunding (7.4%).

Lending, at 72.9%, would make up the bulk of the funding volume. But if equity crowdfunding doubles every year – like the rest of the crowdfunding market has – then analysts see it reaching about $36 billion by 2020, surpassing venture capital as the leading source of startup funding. If the ACfA can convince legislators to extend the equity crowdfunding market to include unaccredited investors, the potential growth in Africa could be staggering.

LelapaFund is already tapping this market. The Paris-based crowdinvesting platform enables individual investors around the world – mostly drawn from the African diaspora – to purchase shares in African startups and SMEs. Anyone can create an investor account for free (users just need to complete an investor verification form and accept the terms of use), and investors can invest in as many companies as they wish, ‘as long as their personal finances and risk profile are respected’, according to LelapaFund.

Investors on the platform make their return on investment (ROI) when the value of their shares increases. ‘There is no guaranteed ROI but similar investments yield 12% on average,’ it states.

Again, this is a potentially enormous market. Nigerians in the diaspora sent about $21 billion home in 2015, making it the sixth-largest receiver of remittances in the world, according to the Migration of Remittance Factbook 2016. If a portion of that were to be converted to equity crowdfunding, the impact could be immense.

So where does this leave banks as well as other traditional lenders and investors? ‘Rewards-based crowdfunding, like on Thundafund, in no way competes with banks,’ says Schalkwyk.

‘All transactions flow through the traditional banking systems. We do allow or offer the entrepreneur a different way of finding funds to grow the business.’

Enter RainFin. This peer-to-peer lender headquarted in Somerset West allows clients to borrow from or lend to other clients quickly and easily. Or, as CEO Sean Emery puts it: ‘RainFin is a credit marketplace that matches borrowers and lenders, where borrowers conclude a loan agreement to access funding.

‘Lenders price these loan agreements according to their desired return on capital and their perception of credit risk. Lenders benefit by being able to lend money at different interest rates and to different borrowers – thereby diversifying their risk.’

After the initial Barclays investment in RainFin in 2014, the two companies worked closely together to refine the original RainFin.com marketplace offering, its supporting operations, credit-scoring methodology and collections capability to align to the regulatory framework, according to Emery.

‘Through Absa and RainFin’s partnership, Absa’s business bankers get the opportunity to offer clients a very efficient digital mechanism to complement their present SME unsecured terms working capital loan customer value proposition, while RainFin can significantly scale the volumes on its marketplace. In addition, Absa is also a lender on the RainFin marketplace,’ he says.

In February, RainFin announced a partnership with Absa (already a 49% equity owner) that resulted in their products being offered to Absa customers. And if that sounds like a traditional financial institution’s response to the crowdfunding phenomenon, it’s because that’s exactly what it is.

‘Yes, the deal between RainFin and Absa is a response to the evolution that is taking place in the finance industry,’ says Emery. ‘This partnership gives SME clients access to the best of the traditional and the new.

‘Firstly, the traditional is that SMEs who are looking for a working capital terms loan of less than R750 000 will have the ability to complete an online loan application and be offered funding by Absa, as Absa is a lender on the RainFin marketplace.

‘Secondly, the new is whereby the SME will also have offers on their loan from other lenders on the marketplace, therefore hopefully allowing them to get the best rate offer on their loan quicker than the manual process used in the past.’

As New Harbour Distillery’s founders raise a glass to celebrate its funding milestone, their gain represents an opportunity for traditional lenders. ‘We were stunned that we got these funds so quickly,’ says Du Plessis, reflecting on the crowdfunding experience. ‘Seems there are a lot of people who are willing to contribute to a great idea.’