It is no coincidence that MTN and Vodacom, among the largest mobile operators on the continent by many measures, are comfortably within the top 15 companies on the JSE, when ranked by market value. Mobile phones, more accurately smartphones, are a fundamental part of our daily lives. For some, the phone may be their only computer. And if data is the new oil, in Africa that data is (mostly) mobile. It is this growth that is powering these telecoms juggernauts ahead after decades where voice was the only game in town.

MTN, the largest operator on the continent, has more than 240 million customers across 21 countries in Africa and the Middle East. By comparison, it has twice as many subscribers than its nearest competitor in the region, France’s Orange. Its 2006 purchase of Lebanese telecoms holding group Investcom for $5.5 billion was transformational for the group, giving it access to an additional 10 markets, including the sizeable and important Ghana. Three operations, however, dwarf the other 18. These are Nigeria (its largest market by subscribers, revenue and profit), SA (its second largest) and its 49% stake in MTN Irancell.

The group has been hit by a number of unexpected regulatory crises in the middle of this decade, the largest being the $5.2 billion fine imposed on it by the Nigerian regulator in 2015. The regulator fined MTN for failing to disconnect more than 5 million unregistered subscribers. It took nearly a year for MTN and the Nigerian Communications Commission to settle on the quantum of the fine, which was eventually reduced to $1.7 billion (this dropped even further as the naira weakened).

Coronation portfolio manager Pallavi Ambekar makes the point that in addition to the fine, the Nigerian regulator also proceeded to suspend regulatory services to MTN. ‘The suspension of these services effectively hamstrung MTN’s competitive position as it was not allowed to implement any promotions or new tariffs. This led to a direct loss of market share to competitors. The quantum of the fine and the suspension of services highlighted the extent to which the relationship between MTN and the Nigerian regulator had broken down. ‘The share price reaction to these events was swift and brutal. In the space of three months, the market wiped $10 billion off the market capitalisation of the company, almost twice the initial fine amount,’ says Ambekar.

The fine and the governance failings that it exposed forced the ousting of then group CEO Sifiso Dabengwa as well as a number of MTN Nigeria executives. Chairman and CEO Phuthuma Nhleko returned to lead the group and restore stability. Although he implemented several necessary reforms, the group had no clear strategy. Rob Shuter, a former Vodacom and Vodafone executive, took over in early 2017. Since joining the group, Shuter has been driving a new strategy (‘Bright’) that has galvanised the group.

By 2022, it wants to grow to 300 million subscribers, 200 million of whom will be active data subscribers, and achieve 100 million digital subscriptions (including 60 million for its MTN mobile money service). As at end-June, it had 82 million data subscribers and 30 million mobile money users, showing just how aggressive these targets are over the next four years.

It is clear why MTN believes mobile money (MoMo) is such a crucial growth vector. The opportunity in financial services was first made obvious by Safaricom with its world-leading M-Pesa platform in Kenya and East Africa. MTN says already one in every four active mobile financial services customers in sub-Saharan Africa is an MTN MoMo one, and that these customers each generate an additional monthly average revenue per user of $1.30.

This is significant, given the average monthly revenue per user in markets such as Nigeria and Ghana is just in excess of $4 (in SA, it is closer to $7). The total value of transactions performed by MTN MoMo customers in the first half of this year was $44.1 billion, with MTN processing more than 9 000 transactions per minute.

Shuter has also begun to offload non-core assets, with more than R15 billion to be raised from this ‘realisation programme’. It has sold its operation in Cyprus, reduced its stakes in Ghana and Nigeria following IPOs of those operations on local stock exchanges, and will sell its majority holding in Mascom Botswana. In 2019 so far, it has reported R2.1 billion in divestments, including certain of its e-commerce assets. ‘MTN has a market-leading footprint in key countries that is very difficult to replicate,’ says Ambekar. ‘While not immune to macro pressures, it has a relatively defensive business model. Data penetration across key markets is still at very low levels and growth will be supported by the increased availability and affordability of smartphones.’

Irnest Kaplan, MD of Kaplan Equity Analysts, also makes the point that many of the markets in which MTN operates still have better growth prospects than SA, relatively speaking. Vodacom, a fierce rival in SA, has a far more modest geographic footprint. With 78.9 million customers in SA, Tanzania, DRC, Mozambique and Lesotho, it is the largest by number of subscribers in all the markets in which it operates. It also owns a 34.94% stake in Kenya’s Safaricom, acquired from parent Vodafone in 2018. Safaricom has a further 31.8 million customers.

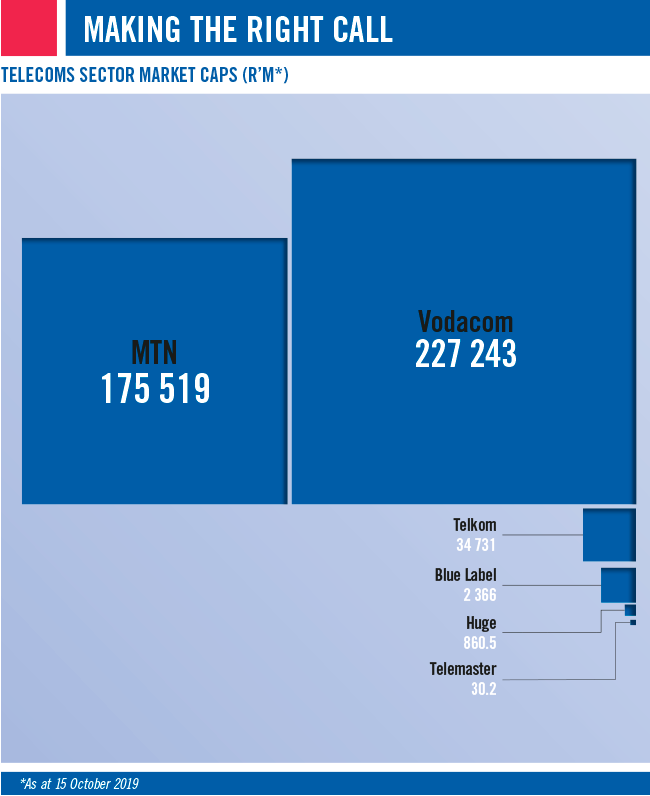

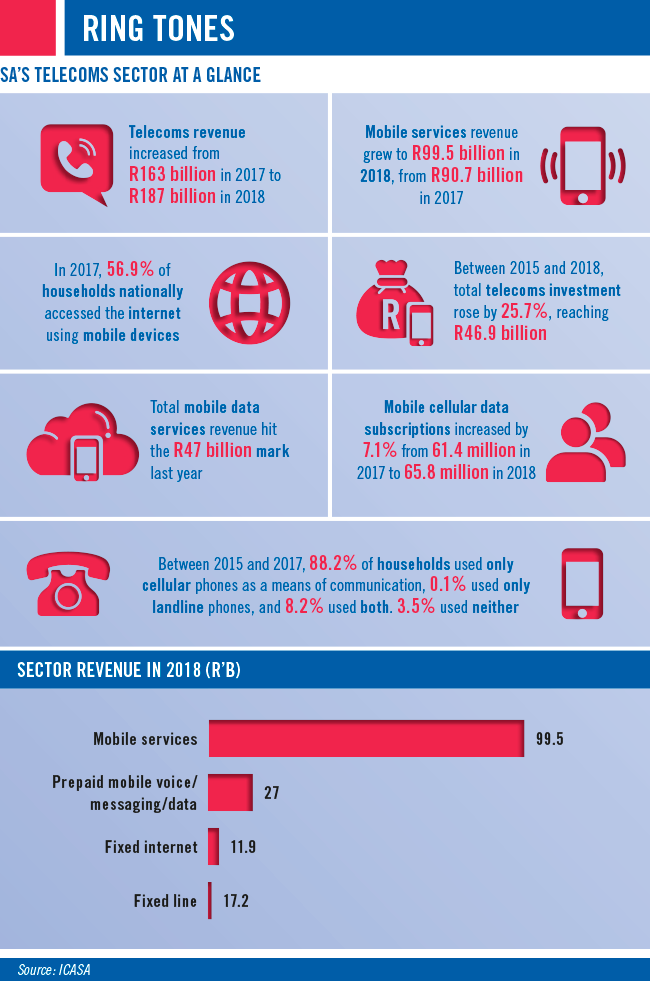

Despite this smaller customer and geographic base, Vodacom has a larger market cap than MTN (R227 billion versus R175 billion, as at mid-October). In the year to end-March, Vodacom reported revenue of R90.1 billion, with data revenue of R27.3 billion. MTN Group reported revenue of R135 billion in the 2018 year, with data revenue just ahead of Vodacom’s. Kaplan says Vodacom has a ‘very commanding position in South Africa, with a strong network locally’. He adds that its global parent Vodafone – one of the largest operators in the world – ‘gives it advantages in terms of experience, strategic insight and buying power’.

CEO Shameel Joosub, writing in the group’s integrated report, says: ‘Our strategy positions Vodacom to be a significant contributor to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as we transition from a traditional telco to a fully fledged digital services company. We are already leading in the implementation of big data, artificial intelligence and robotic process automation, which is enabling us to optimise revenue, operate more efficiently and maximise our investment returns, laying a strong foundation for significant further growth.’

Like, MTN, it too is pushing hard in the area of financial services. With M-Pesa, it has the pre-eminent global mobile money platform. Earlier this year, it announced a deal to acquire, together with Safaricom, the M-Pesa brand and intellectual property for around $13 million. According to Reuters, the transaction will mean significant savings in royalties paid to Vodafone for both Safaricom and Vodacom, and will enable the African operators to focus on expanding the services to new markets.

Including Safaricom, it processed 11 million transactions worth R2 trillion on M-Pesa for 36 million customers last year. And it is Safaricom that offers a glimpse of just how large a contributor to revenue M-Pesa could be: nearly a third of its service revenue is from the platform.

The group says it will look to entrench its leadership in mobile money. In SA, though, repeated attempts to launch M-Pesa have failed. In its home market, its financial services proposition is focused on insurance, payments and lending. The unit has 10 million customers – one in four of its base – and contributed R1.6 billion in revenue last year. For now, its Airtime Advance product, which allows subscribers to recharge and pay later, makes up the rump of this unit.

One might argue that Vodacom would not have been as successful over the past decade had Telkom not decided to sell its 50% stake in the operator. It sold a 15% stake in Vodacom to Vodafone and unbundled the rest to shareholders by listing Vodacom. Since that decision in 2008, Telkom, the third-largest listed telecoms provider by market value (R35 billion), has had a tumultuous time. The decision has been described by some former executives at Telkom as ‘one of the company’s biggest mistakes’ and meant that it had to build out a mobile network of its own. This launched in 2010 (first as 8ta, later rebranded as Telkom Mobile), but took until 2016 to turn a profit. Until that point, cumulative losses totalled R7 billion. By the end of this financial year (March 2020), it will have clawed back all of those historical losses.

The mobile business is at scale: it had 9.7 million active customers at the end of March. And, mobile is now a bigger business for Telkom than its fixed-line consumer business, with revenue of R10.9 billion versus R8.3 billion. Importantly, the mobile unit is the sole reason for the profitability in Telkom’s consumer unit (its fixed line business is losing money). The number of landlines has roughly halved since a peak of around 5 million in 2001. Kaplan highlights how challenging it has been and will be for Telkom to ‘overcome the decline in the fixed space’.

In Telkom’s most recent integrated report, CEO Sipho Maseko says the group’s ‘technologies and spectrum optimal utilisation position our mobile offering in a commanding position as the world migrates from voice to data. We aim to lead in the fourth and fifth generation – 4G and 5G – wireless technology sphere’. The three other listed companies in the sector are far smaller than the first three operators.

Blue Label Telecoms, a distributor of airtime and value-added services, is worth just R2.3 billion, having lost 85% of its market value in the past three years. The trouble started in 2017 when it announced two sizeable transactions. It would buy 45% of Cell C for R5.5 billion in a ‘transformational’ deal, and it would acquire handset distributor 3G Mobile for R1.9 billion. This left a historically cash-flush business burdened with debt.

Cell C’s struggles have been widely reported, and new CEO Douglas Craigie Stevenson and CFO Zaf Mahomed are working to stabilise and turn around the business. Key to this is the pending recapitalisation of the operator, a process being led by Blue Label.

‘Blue Label has demonstrated how strong they are in the space of distributing mobile airtime and other services,’ according to Kaplan, who welcomed its decision to reduce debt, divest non-core assets and get back to basics. There are two smaller businesses listed in the telecoms sector of the JSE: Huge Group and Telemasters. These have market values of R860 million and R30 million, respectively. The former provides fixed and mobile connectivity as well as network solutions to 45 000 clients, and the latter is a niche voice and data provider. In May this year, Huge acquired a shareholding in Pansmart, a distributor of Panasonic voice, video and CCTV products in the country. According to Huge, Pansmart is a ‘strong challenger’ in the SA PABX market.

While telecoms is ‘quite a mature sector’ given the saturation in mobile markets and with fixed lines in decline, Kaplan says it remains defensive. ‘People and businesses will continue spending on telephony and telecoms in both good and bad times. It’s one of those things you have to have.’