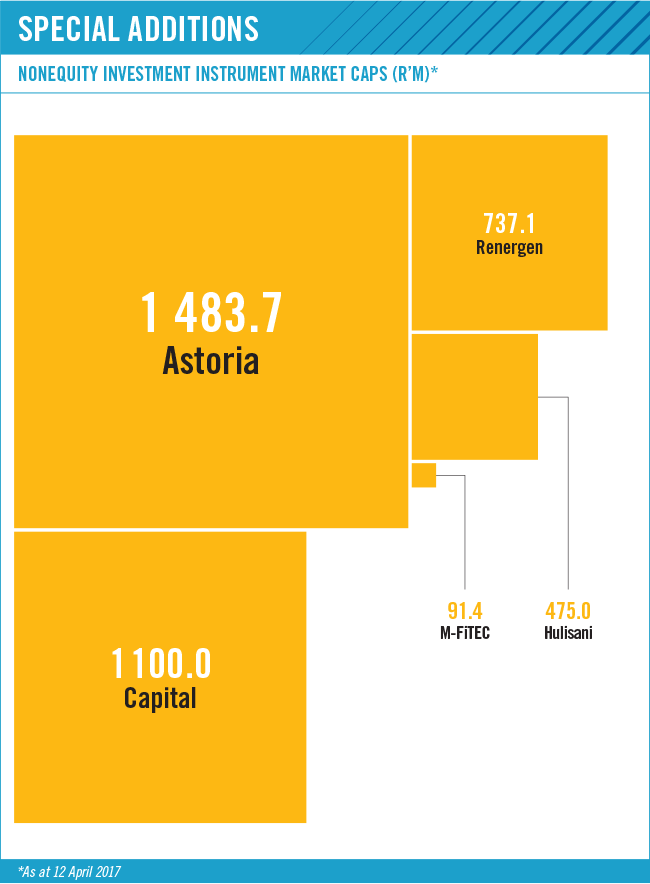

Four out of five of the companies in the nonequity investment instruments sector are in the new special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) category, which the JSE approved for listings relatively recently. SPACs are a category in which investors probably need to do the most work depending on their appetite for risk – more particularly, what proportion of a portfolio should be assigned to what is considered a category for ‘risk tolerant’ investors, according to the JSE.

While this introspection is important, it is in addition to the regulations and characteristics of SPACs (and all this is before evaluating the specific companies). So why would investors bother with the extra homework?

The reason is SPACs offer investors the potential for above-average capital growth in promising businesses that most JSE-listed companies have little exposure to. This is from start-ups to already profitable early-stage enterprises. It goes without saying these are generally long-term investments – the caveat is that they are riskier than ‘blue chip’ equity investments.

As a result, they are appropriate investments for high net-worth individuals and, importantly, they can also have a place in pension funds, especially those that are meeting client expectations. In other words, funds that are relatively buoyant.

Pension investments in SPACs have no public regulatory limitations specific to the SPAC category, according to the JSE. Indeed, the same limitation rules that apply to all other equities also apply to SPACs. However, there can be self-regulation by pension funds if the ‘risk mandates’ of individual pension funds constrain exposure to SPACs.

First listed on the JSE in 2014, SPACs are similar to private equity funds in that they privately raise capital for unspecified investments. An important differentiator from private equity funds, however, is that SPACs are listed on public markets with the requirement to publish information for the broader investment community.

‘The opportunity to list a SPAC, which is best described as a reverse initial public offering, gives investment companies an additional platform to raise immediate capital with which to acquire assets, while investors benefit from the liquidity and transparency associated with investing in a listed company,’ Donna Nemer, JSE Director of Capital Markets, said at the time of the first SPAC listing.

Another relevant difference is that pension fund investments in private equity are limited by regulations to 10% of the pension fund, unlike SPACs, according to the exchange.

Investments in SPACs are also somewhat easier to get in and out of, compared to private equity funds. A note of caution is that until an acquisition is made by the SPAC, they are less liquid than investments in many established listed companies, with relatively low volumes traded on the JSE.

While there are similarities with mainstream listing requirements, there are also important differences. The primary distinction is that SPACs are able to raise funds without any operational assets. To protect investors in these cash ‘shells’, key safeguards have been built into the listing requirements.

One of these is that shareholders funds are held in escrow accounts, much like the trust accounts that attorneys are required to use when you buy a house. This regulation aims to ensure that the bulk of funds invested are kept separate from those used to run the office of the SPACs, including paying salaries to a small team.

A second is that if the SPAC makes no investments in viable companies (those that have the resources to continue operating until there is evidence otherwise) in the first two years, shareholders are entitled to have their investments returned to them.

Like most sectors on the JSE, the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) is the biggest player in SPACs. The investment manager of government pensions owns even bigger stakes in the SPACs category than in most others. This is because the PIC (beyond its primary role as a responsible investor on behalf of pension funds) has a secondary mandate to invest in developmental infrastructure. These aims can be at odds with each other and are not without a measure of controversy.

Unlike most private equity funds, SPACs are also sector-specific, giving investors a chance to deploy capital in new growth industries that are not yet represented on stock exchanges.

The nascent ‘clean energy’ sector is an industry that ticks many boxes – it’s growing and has the potential to become a ‘mainstream’ category. It is also providing additional electricity that the economy will one day need.

Energy investor Hulisani is the first SPAC on the JSE to ‘graduate’ to an ordinary listed investment company. This after Hulisani announced it had completed the process of buying a 7% stake in the Eastern Cape’s 80 MW Kouga wind farm for R129 million. Before that, Hulisani raised R500 million in a private placement as part of the JSE Main Board listing process in April 2016.

The wind farm has a 20-year supply agreement with Eskom. On account of Kouga being a viable asset, the investment potentially marks the end of a milestone in Hulisani’s developmental phase. If concluded, the deal will catapult its investor profile from a speculative investment towards one that’s not simply revenue generating but profitable too.

This would align the Kouga investment with the relatively steady utility sector. The nature of the sector should ensure it makes a positive return through the ups and downs of the economic cycle.

Furthermore, Hulisani (which is controlled by public sector pension funds) intends to raise as much as R4 billion in further capital to make much bigger (and currently) undisclosed investments in energy. The PIC owns 45% of Hulisani, the Eskom Pension Fund owns 15% and the Unemployed Insurance Fund owns 5%.

In February 2017, a very different sort of SPAC announced it was in the process of buying three companies in the automated payments category of financial technology (fintech). According to the SPAC – services sector investor Capital Appreciation (CAPPREC) – two of the purchases were already profitable. CAPPREC, which was the first SPAC to list on the JSE’s Main Board, is spending R928 million on the acquisitions.

CAPPREC counts Patrice Motsepe’s African Rainbow Capital as an investor, and the board includes former SABMiller chairman Meyer Khan, PIC CEO Dan Matjila and Netcare co-founder Motty Sacks. For investors considering a SPAC investment, an evaluation of the non-executive directors and hands-on management is probably the most important research they can do given that at the early stage they will be investing in a cash shell without operating businesses.

At the CAPPREC listing in October 2015, Sacks underlined how meaningful an appraisal of the quality of directors is to investors in SPACs. ‘My founder colleagues and I are delighted with the outcome of the capital raising. Where several quality enterprises were competing for investment in the same week, to have raised R1 billion for a new SPAC – a company with no operating assets – is not only a wonderful expression of support but, more particularly, an acknowledgement of trust in the experience and integrity of our leadership.’

CAPPREC’S February acquisitions included African Resonance Business Solutions, which doubled after tax profits in financial 2015 and 2016, reporting a profit of R59 million in the six months to August 2016, and Synthesis Software Technologies. A third, Rinwell (which owns Dashpay), reported a loss of R5 million in the half-year to June 2016.

Another SPAC in the fintech space, M-FiTEC International, listed on the AltX in November 2015. A year later, however, it was still in negotiations to buy viable assets, meaning it has until mid-November 2017 to make an investment, otherwise it will be required to return the cash to investors. This amounts to the R76.2 million raised in the listing plus interest, less expenses.

Alternative energy investor Renergen, which also counts the PIC among its shareholders, does have an operating asset, albeit in a start-up phase. This is in the form of Tetra4, the only onshore petroleum and natural gas field in SA, located in the Free State. Renergen generated its first revenue in the six months to August 2016 after Tetra4 supplied the helium equivalent of 63 000 litres of diesel to transport company Megabus.

Furthermore, the gas compression plant supplying Megabus is now fully operational, according to Renergen. Following the Tetra4 acquisition, Renergen reported a total comprehensive R9 million loss to owners of the parent company in the six months to August 2016.

While losses in a start-up phase are expected, Renergen sought to reassure investors, saying it continued to operate as a going concern and that total assets remained significantly higher than total liabilities. ‘The board of directors of Renergen has ensured that the company has sufficient cash resources to meet its strategic objectives and financial obligations,’ said Renergen.

In 2016, it announced that Tetra4 had contracted the helium offtake to global gas supplier Linde Group, parent of JSE-listed Afrox. ‘The contract will enable Afrox to locally source and supply helium to numerous specialised and industrial local markets by 2018/19,’ said Renergen. Afrox will operate the processing plant and market the helium.

Chris Gilmour, analyst at Absa Investments, cautions that potential retail investors in SPACs must have ‘a much higher risk profile’ than those considering traditional listed equities. Then they need to spend a lot of time doing their homework.

‘Investors interested in SPACs need patience, dedication and ideally some technical background in the particular industry,’ he says, adding that SPACs should look to acquire ventures that are already operational, as opposed to being at an exploratory stage. SPACs keen to attract capital are in a position to offer potential investors time with management – and investors should take advantage of this.

Astoria (which is not a SPAC but rather a JSE-listed investment company that includes ‘nonequity’ investments) allows South Africans to invest offshore in one share without the limitations of exchange control regulations.

It is managed by Anchor Capital and invests primarily in overseas equities. Astoria also offers limited exposure to unlisted alternative assets, such as private equity.

Astoria made the headlines when the board unexpectedly approved a share incentive scheme that permitted Astoria to offer up to 10% of the issued shares to executive directors at a time when the share price was low.

While no price was disclosed, investors feared executive directors would be offered shares at a discount to this already low price and unduly benefit. Astoria claimed it would not issue all the shares but eventually retracted the entire share scheme in a victory for corporate governance.

While there are major differences between Astoria (which invests primarily in listed companies and funds) and SPACs (which invest in operational enterprises), the two do have one thing in common – both offer investors the opportunity to invest in public companies outside the traditional listed space. Remember though to do your homework – access to information is crucial to making well-informed decisions.