Many of the companies in the JSE food-producers sector trace their origins to the first half of last century; some go even further back to milling companies established in the late 1800s. Tiger Brands, for example, listed on the exchange in 1944 as Tiger Oats, which itself had been established in the twenties. Some like AVI began as part of a conglomerate (Anglovaal, which originated as a gold miner).

Over time, empires would be amassed, and then various parts would be carved off. By the 1980s, Tiger was majority-owned by industrial conglomerate Barlow Rand (now Barloworld) and it, too, had built up an impressive portfolio. In the early 2000s, it began unbundling these assets, including Spar (yes, Spar was owned by one of the country’s largest food producers), poultry producer Astral Foods and pharmaceutical company Adcock Ingram.

Today, the 13 listed food producers on the JSE together have a market value of just more than R100 billion. Small Talk Daily Research analyst Anthony Clark makes the point that it is key to appreciate that, because of diverse factors and input costs, beyond that people need to eat as a core driver, one cannot hold a view of the overall sector. He says many of these shares are directly influenced by volatility in the price of soft commodities such as maize, which in turn are impacted by floods, drought, exchange rates and the price of oil.

Tiger Brands is the largest in the sector, with a market cap of R39.1 billion. It produces a number of the country’s best-known food brands, such as Tastic, Fattis & Monis, All Gold, Koo, Albany, Jungle Oats, Oros and Beacon. In recent years it acquired Crosse & Blackwell, as well as Mrs Ball’s chutney.

Yet, the group is still recovering from a bruising period of expansion into East Africa and West Africa, which has taken a number of years to unwind. It famously sold Dangote Flour Mills back to Aliko Dangote for $1 in 2015 after losing billions in Nigeria. In addition to this, a 2018 listeriosis outbreak traced to one of its factories tainted the company, knocked profits and forced it to sell its (Enterprise) meat-processing business. In 2020, despite disruptions caused by COVID-19, it reported revenue of R29.8 billion. Nearly half of this (R13.9 billion) was generated by its grains (rice, pasta, milling and baking) unit.

Tiger has two large rival food producers in SA, but neither is directly listed. Pioneer Foods (which was formed by the eventual merger of Bokomo and Sasko in 1997) was acquired by PepsiCo in 2019, while Premier Foods (with its origins as SA Milling in 1891, which made Snowflake) is one of a few core holdings of JSE-listed investment company Brait.

The second-largest food producer by market cap (R25.8 billion), AVI Limited, isn’t exclusively a food producer. Sure, around 70% of its operating profit for the six months to end-December came from Entyce beverages and Snackworks units. These have their roots in the former National Brands Limited and produce many popular tea, coffee and creamer brands, including Ciro, Five Roses, Freshpak, as well as Bakers, Baumann’s, Pyotts and Provita biscuits and Willards crisps. It also owns fishing company I&J, but AVI entered the fashion industry in the early 2000s. It now has a business that comprises the Spitz, Kurt Geiger, Gant and Green Cross labels and stores. This is relatively small (15%) in its portfolio but has contributed significant profit growth over the past decade.

Tiger’s most recent unbundling, in 2019, was that of fishing company Oceana. It sold some of its stake to empowerment group Brimstone (which itself unbundled Sea Harvest to shareholders) and unbundled the rest. Oceana’s market value of R9.2 billion ensures it ranks as ‘one of the top 20 seafood companies in the world by market capitalisation’, according to the company. It has operations in SA (with well-known canned-fish brand Lucky Star), Namibia and the US, through Daybrook Fisheries, which it bought in 2015. This purchase allowed it to further diversify its fish supply and earnings. In 2020, more than half of the group’s earnings were from markets other than SA, with its home market and Namibia accounting for just 30% of its fish supply.

According to Clark, the CEO of Oceana Holdings Imran Soomra recently reported that ‘their Q1 canned-fish Lucky Star volumes are tracking better than the negative declines in general grocery basket volumes but they [Oceana] are still down by around 3% in the quarter. They anticipate no canned-fish price increases for the next 12 months’.

Sea Harvest catches, processes and markets Cape hake, horse mackerel, pilchards, tuna anchovies and prawns from SA, as well as prawns from Mozambique and Western Australia. It purchased Ladismith Cheese in 2018 to further diversify from its core local fishing operation.

The third fishing group on the local bourse is Premier Fishing and Brands, which was unbundled from African Equity Empowerment Investments and has a market cap of R234 million.

Clark points to a recovery in white fish demand from Europe as a key driver of revenue and earnings growth for the fish producers.

The chicken sector also has a number of companies listed on the JSE, but only one, Astral Foods, is a pure-play poultry producer (it is also the country’s largest). It has a market value of R6.6 billion, and the producer’s annual results for 2020 reveal the impact of (predominantly) higher maize prices. Revenue was up 5%, but profits declined by a similar percentage.

RCL Foods, valued by the market at R9 billion, is a far bigger company than just its (struggling) Rainbow Chicken unit. Majority owned by Remgro, RCL owns a sizeable sugar business (Selati), bakery Sunbake and a number of other grocery brands, including Epol, Nola, Supreme flour, Ouma rusks, Number 1 Mageu and Piemans.

Clark says there has been ‘encouraging price firming in medium frozen whole birds and individual quick-freezing [IQF] chicken, but that could be a factor of the traditional pre-Easter price movement. As South Africa heads into winter and the spectre of a COVID-19 Wave 3, the ending of some government support grants and rising inflationary pressures from fuels and food, the on-the-ground forecast for poultry cannot be said to be rosy’.

The other listed poultry producer is Quantum Foods, with a market cap of R1.2 billion. It is the largest producer of eggs in the country.

Two of the more recent arrivals in the listed sector are Rhodes Food Group (RFG), which listed in 2014, and Libstar, which came to the market in 2018. Both were acquisitive in the run-up to, as well as following, listing. Today, RFG looks very different from the business that started as Rhodes Fruit Farms in 1896. It owns Pakco (including Bisto and Hinds), Bull Brand as well as a number of pie producers across the country.

Libstar owns well-known brands Lancewood and Denny and has also acquired a number of producers that manufacture private-label and store-brand goods for supermarkets. One of its units, Dickon Hall Foods, has manufactured Mrs Ball’s chutney under contract for Tiger Brands since 2000. In a similar relationship, Dickon Hall Foods also produces Knorr salad dressing (among other products) for Unilever, which has been in place for a decade. It also makes all Nando’s sauces. Its Rialto business is the exclusive importer and representative of a number of well-known brands, including Tabasco, Kikkoman, Kiri, Laughing Cow and Lurpak.

Producing private-label and so-called ‘own-brand’ goods for stores is big business. Across the market, private-label goods now account for approximately 15% of sales. For the largest supermarket group in the country, Shoprite Holdings, this figure is 17.7% – significantly higher than the 16.1% in 2019. The group says the ‘need for more value post-COVID is driving adoption of private label’. Across the group, it has 29 private-label brands, each with more than R100 million in annual sales. Its Shoprite Ritebrand is ‘now in one out of five Shoprite baskets’, while Checkers Housebrand delivered volume growth of one-and-a-half times that of a typical store.

Ahead of its listing in 2018, Libstar disclosed that in excess of 42% of group revenue came from the manufacture of ‘dealer-own brands and private-label products’. It produces such products for Woolworths, Shoprite Checkers, Pick n Pay, Spar, Massmart, European discount retailer Aldi, US grocery retailer Trader Joe’s and Canada’s Loblaw.

Its Ambassador Foods unit, for example, has supplied nuts under Woolworths’ dealer own brand for approximately two decades, while Rialto Foods supplies pasta to the retailer too. Other examples are Libstar’s Lancewood, which provides Shoprite Holdings with cheese under its Crystal Valley dealer own brand.

The rise of private-label products has impacted the major branded food producers, chiefly Tiger Brands, which has built its entire business on branded fast-moving consumer goods. The producer last year surprised the market by announcing that ‘opportunities in servicing private label’ were ‘being explored with customers’.

This emerged following a strategy review by new CEO Noel Doyle, who said that the business had ‘done some private label in the cereals space, so we’ve always looked at private label with a degree of flexibility’.

However, he cautioned that ‘a lot of private label is still done opportunistically and we wouldn’t want to be involved in an opportunistic on-off supply’.

He is clear that, although late to the party, Tiger clearly sees an opportunity. ‘We have to recognise that private label is here to stay and it’s probably a phenomenon where you’re going to see some growth, particularly in the next 12 to 18 months.’

As an extension of their private-label relationships, RFG, Libstar and RCL Foods also produce ready-meals and prepared food products for national retailers such as Woolworths, Pick n Pay and Checkers.

Sugar producer Tongaat is undergoing a turnaround after being rocked by an accounting scandal. With operations throughout Southern Africa, Tongaat is one of the region’s largest sugar producers and has a market cap of about R1.35 billion.

Smaller Crookes Brothers also grows sugar cane, but in addition it farms bananas and macadamias, while AH-Vest Limited owns All Joy, a manufacturer of tomato sauce and other condiments.

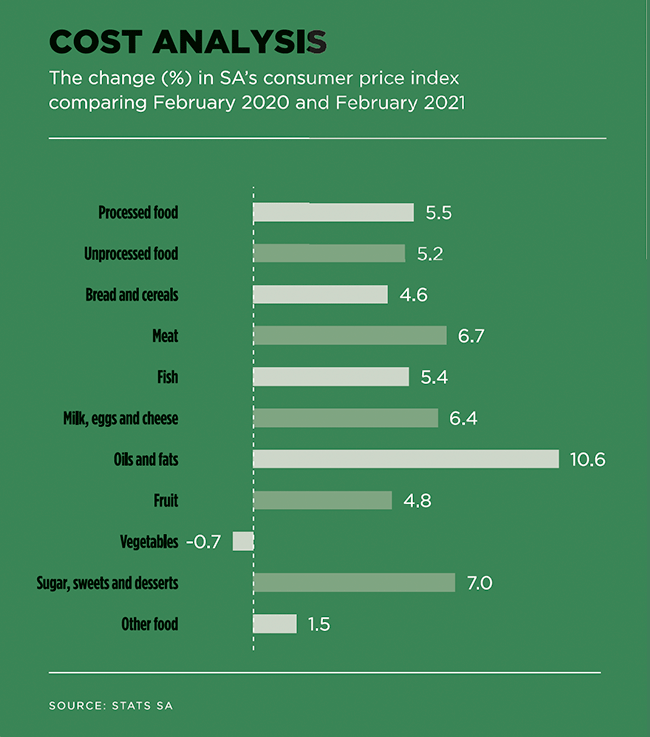

Clark says the full effect of high soft-commodity prices is only now feeding through into the system. Along with that, ‘inflationary pressures are building up’ including higher packaging prices, transportation costs and administered tariffs. He echoes recent sentiments from the listed food producers and says that the consumer is beginning to trade down; they are feeling the strain.

‘Anecdotal evidence I have received [sees] CEOs of leading food producers comment on the distressed consumer trading down from basic staples like rice and bread back to mealie meal as an affordability option,’ he says. ‘This is concerning.’

A broad recovery in the sector, which will struggle to recoup all of these rising costs, will require sustained growth in the whole economy along with an uptick in employment. Much therefore rests on President Cyril Ramaphosa’s Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan.