Israel has more companies listed on New York’s technology-heavy NASDAQ exchange (117) than any country other bar the US, Canada and China. This technology and innovation edge is unlikely to diminish. Israel spends more per capita on research and development – just shy of 5% of GDP – than any other nation worldwide.

Israel has gone from underdeveloped poverty to developed country status in not much more than half a century. The original settlers were strongly influenced by the European social-democratic tradition and there was a heavy focus on the instruments of social cohesion, including the famous kibbutzim or agricultural collectives. But after a catastrophic bout of inflation, reaching close to 450% in 1984, following a decade of stagnation, market-oriented structural reforms were introduced, paving the way for rapid growth since the 1990s.

Some Israeli commentators consider the 1985 reform programme to be ‘the day Israel’s modern economy was born’. At the time, government’s share of the economy was 76%, effectively squeezing out private initiatives. The ‘stabilisation plan’ was a painful shock, involving huge government spending cuts, but it worked.

The Israeli reforms are sometimes regarded as a model for countries facing the sort of problems facing Israel in the 1970s and early 1980s. An austerity programme, designed by outside technocrats, was not dissimilar to the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) policy that was introduced by the SA government in 1986. The difference was that the Israeli reforms – while facing opposition – succeeded and became permanently embedded in the national economy. SA’s gains, by contrast, were frittered away during the state capture years.

Israel today has an annual GDP per capita of nearly $40 000, higher than most developed countries. Moreover, the country is still surging ahead. Arthur Lenk, Israeli ambassador to SA from 2013 to 2017, points out that ‘for all the pain and tragedy, COVID-19 was good for the Israeli economy’. With its competitive advantages in high-end technology, trends towards remote working and greater digitalisation of economies enabled Israel to thrive.

According to Nava Feseha Getahun, economic mission head of the Johannesburg-based Israel Trade Mission to South Africa, ‘2021 was the first year that Israel’s trade in services was greater than out-trade in goods’.

Trade in services is a World Trade Organisation category that includes software, data technology and communications. She adds that ‘over four years, 2017 to 2021, Israel’s exports to South Africa in this category more than doubled, from $14 million to $30 million’.

Israel looks likely to achieve an economic growth rate of above 5% in 2022, higher than any other developed country, according to Bloomberg. The unemployment rate in 2022 stands at 3.5% and inflation is expected to be around 4.3%, about half that of the US and the EU. As reported by the Washington Post, the shekel is the world’s best-performing currency and the only one that strengthened against the dollar over the past decade.

‘Israel sometimes calls itself a “start-up nation” – a reference to the country’s booming technology sector,’ Lenk points out. ‘South Africa could take lessons from this success.’ SA wants to grow its tech sector while Israel already has, he adds. Part of the formula is being business friendly – an area where SA could do more – but other elements are less easily replicated.

Israel’s technical education system is top class, its venture capital industry large and innovative, and its national pool of ideas has been continually refreshed by well-educated immigrants. Government support in the form of incubators and tax breaks for innovation is extensive. Some 300 research and development centres have been established in Israel by multinational corporations, two-thirds of them US-based. Microsoft, Facebook and Google are among the tech giants that have innovation hubs in Israel.

In any case, innovation is ‘pretty much a part of Israel’s DNA’, says Getahun. Lenk agrees. ‘Israel is an extremely dry country with few natural resources,’ he says. From the foundation of the Israeli state in 1948, agriculture and food security were life or death obsessions. Agriculture was the first major area of innovation, starting at a time when Israel was a very poor and insecure country.

Jonathan Shapiro, CEO of the South Africa-Israel Chamber of Commerce, says that the organisation’s members ‘work in a quiet and determined manner to introduce Israeli technology to areas of significant need’ in SA. ‘If you want a technical solution to a problem, there’s a good chance you’ll find it in Israel.’

Particular areas of interest that the chamber is aware of are cybersecurity and medical technology, a deep and established relationship in agritech as well as water treatment and desalination plants.

SA is also largely an arid country. Netafim, an Israeli manufacturer of irrigation equipment with manufacturing facilities around the world, including Kraaifontein near Cape Town, points out that ‘South Africa has 60% less available water than the world average’. The company offers not only drippers and sprinklers but also software-based monitoring and control systems.

The match with the sophisticated end of SA’s horticultural and agricultural industries is obvious. ‘You almost have to work to make this [agritech] relationship not succeed,’ says Lenk.

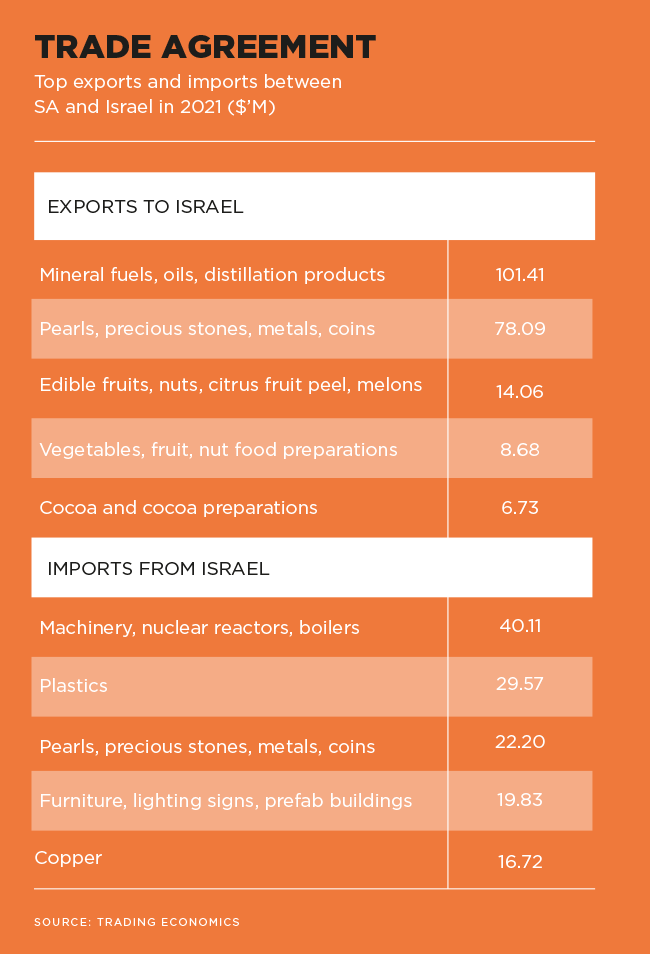

Indeed, while technology may be glamorous and attention grabbing, it should not be forgotten that agriculture accounts for much of the trade between Israel and SA. ‘Nearly half of Israel’s exports to South Africa are machinery and chemical, both destined for agricultural applications,’ says Getahun. In addition, she says, Israel is an important market for SA fresh agricultural products.

A casual glance at trade figures may suggest a big decline in SA-Israel trade in recent years. Trade volumes peaked at $1.19 billion in 2012 but in 2021 were much lower at $250 million. However, as Lenk points out, these aggregate numbers are deceptive. The biggest item traded between the two nations used to be coal from SA followed by diamonds. While the diamond trade continues to thrive, the coal market has dwindled to zero over the past decade, as Israel has transitioned to natural gas.

It is Israel’s high-tech exports that represent the real change in the trade basket. This is in marked contrast to the situation when SA started trading with Israel after the predominantly Jewish state’s foundation in 1948. ‘The SA-Israel Chamber of Commerce was initially designed to support the then fledging state of Israel,’ says Schapiro. He adds that ‘motivated by Zionist ideals, the idea was to provide funding support, investment flows and technology enhancement from what was then the South African industrial powerhouse’.

Product sophistication is now heavily weighted in Israel’s favour. ‘But remember, the two economies are still intensely compatible,’ says Lenk. SA is ‘well placed to take advantage of Israeli technology and innovation’, he argues.

Getahun says it is precisely in this area that the Israel Trade Mission hopes to see growth in the future. ‘This is a very busy sector for us. We expect to see a rise in software and services while we keep the relationship going in agriculture at the same time.’

How is trade and business affected by the now frigid diplomatic relationship between SA and Israel? Apartheid SA had a relationship of close technical co-operation with Israel, especially in military areas. There was considerable rapprochement after 1994 with Nelson Mandela saying he respected ‘Israel’s right to exist within secure borders’, but was also concerned about ‘Palestinian rights’. Mandela visited Israel in 1999.

However, the Palestinian issue has continued to fester and SA has adopted a more critical position on the matter. SA withdrew its ambassador in 2018 and downgraded its embassy to a liaison office. Israel, however, continues to have an ambassador in Pretoria.

‘Israel and South Africa may not have a particularly warm diplomatic relationship but there is a huge range of business-to-business partnerships,’ says Lenk. He argues that the diplomatic impasse is not particularly important to business relationships.

‘It’s simply one more complicating factor for Israeli companies looking to do business with South Africans.’ He adds, though, that this is of little consequence to the Israeli economy.

Relations may perhaps not be warm at a government level but Israel can be an important partner especially with regard to technological innovation.