At the end of January, two consignments of manufactured goods were dispatched from the Port of Durban to Kenya and Ghana. The goods – refrigerators, home appliances and mining equipment manufactured in SA – were the first to be traded between these three countries under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement.

Standing on the quayside, wearing a high-visibility vest and a hard hat, President Cyril Ramaphosa told the attendant crowd that ‘this shipment demonstrates that the African Continental Free Trade Area is a reality’.

Ramaphosa went on to say that the trade ministers of African countries ‘have been finalising the rules of origin for what constitutes an African product […] and that the products we trade among ourselves must truly be “Made in Africa”’.

Some self-congratulation is in order, says Gerhard Erasmus, trade law expert and professor emeritus at Stellenbosch University. An enormous amount has been accomplished since the initial treaty or ‘founding instrument’ was signed at Kigali in March 2018. ‘But this is a work in process,’ he says. ‘We have not yet established the deep institutions that full continental trade integration requires.’

A paper published by Brookings earlier this year on trade and regional integration points out that it took the EU 25 years to establish a single market. ‘Economic balkanisation has plagued the continent ever since colonial times. Ultimately, there is no real viable long-term strategic alternative if Africa wishes to attain its developmental goals and aspirations,’ it states.

The impact of the AfCFTA is not yet visible. ‘If you scour the data on intra-African trade, there is not yet much evidence of an upsurge in the amount of goods being traded,’ the report notes. However, ‘progress with the legislative architecture has been impressive’.

Erasmus says that some of the critical protocols are still under negotiation. Among other things, agreement on harmonising competition policy, investment, intellectual property, digital trade and what he refers to as ‘the more difficult rules of origin areas – especially textiles and auto manufacturing’, are still being negotiated. He points out that the AfCFTA is ‘very much a 21st century trade agreement’. It must account for a much wider range of activities and technologies than trade agreements did in the past.

Most importantly, says Erasmus, tariff negotiations are not yet complete. The 54 member countries of the AfCFTA have made ‘provisional offers’, some of which apply immediately but others will only be implemented over periods of up to 10 years, measured from 1 January 2021.

The goods that left Durban at the end of January are part of the AfCFTA’s Guided Trade Initiative (GTI), which began in October 2022. ‘This is a pilot project to test the operational instruments of the AfCFTA and to demonstrate how trade under the AfCFTA will work,’ according to Trade Law Centre (Tralac) chief executive Trudi Hartzenberg. ‘It’s intended to identify challenges with administrative and other procedures, which can then be addressed.’

Hartzenberg points out that only a limited number of countries are participating in the GTI – eight initially (Kenya, Cameroon, Ghana, Rwanda, Tanzania, Mauritius, Tunisia and Egypt) – across a limited range of goods. SA joined the GTI on 31 January, with consignments destined for Kenya and Uganda. Currently SA can trade with Algeria, Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda and Tunisia.

‘The GTI is designed to test the administrative arrangements in practice,’ she says. ‘The 96 products eligible include things like horticultural products, ceramic tiles, tea, batteries, air-conditioner parts and other manufactured goods. It does not apply to services, although there are indications that a GTI for trade in services may be also be developed.’

While it is early days yet, the GTI’s outcomes have been somewhat ambiguous. ‘Customs and other officials based in the exporting countries issue rules of origin and sanitary and phytosanitary certificates for products. These are checked at the ports of entry of the importing countries, and this may be where problems are identified,’ says Hartzenberg.

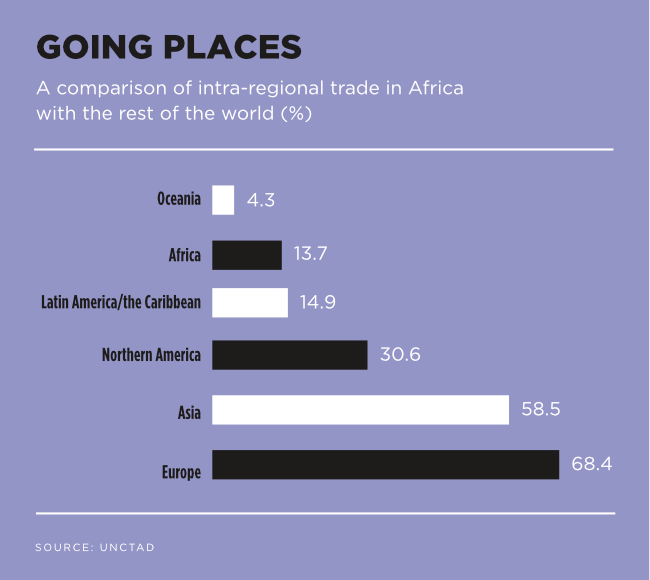

There can be no doubt that more trade between African countries is highly desirable. According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), around 86% of Africa’s exports go to the outside world, not other countries on the continent. By contrast, 68% of Europe’s trade is between EU member states, with a corresponding figure of 58% for Asia.

This is a self-reinforcing pattern of dependency that retards continental development. ‘Africans are principally exporters of raw materials, selling rocks and black liquid to the world, instead of harnessing our oil and the minerals to industrialise the continent,’ according to Ramaphosa. The objective of the AfCFTA, he observes, is ‘to create the world’s largest free trade area by number of countries and offer investors access to a rapidly expanding market of 1.4 billion people’. Free trade within the continent is expected to boost manufacturing and create ‘regional value chains’, which are the holy grail of development economics.

Hartzenberg points out that the emerging critical minerals sector is an example of the sort of desirable regional value chain that may be in the process of emerging. Lithium-ion battery minerals are mined in the SADC – cobalt in the DRC, lithium in Zimbabwe and graphite in Mozambique. ‘There is potential for these countries to co-operate in manufacturing lithium-ion battery precursors,’ she notes. An agreement was signed last year, between Zambia and the DRC, to establish a special economic zone to pursue exactly this goal.

Hartzenberg says that non-tariff barriers constitute more threatening impediments to intra-African trade than tariffs. ‘This is where the rubber really hits the road. We’re only just starting to explore the complexities of implementation,’ says Hartzenberg. ‘Things such as border post delays, roadblocks, crime, potholes and other poor infrastructure cannot be wished away at the stroke of a pen.’

Erasmus says that the AfCFTA does not replace existing trade blocs in Africa. ‘Under the principle of acquis, the agreements that underpin bodies [like the] the SADC free trade area, the Southern African Customs Union [SACU] and the East African Customs Union, remain in place. These free trade institutions are not going anywhere,’ he adds.

‘Implementing the AfCFTA does not mean abandoning the achievements of the past. It aims to use these as the building blocks for the future,’ says Hartzenberg. That said, she believes there is a key role to be played by the continent’s anchor economies; the more sophisticated ones with more manufacturing capacity than their neighbours.

‘South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya have large positive trade balances with their continental partners. South Africa’s to the rest of the continent were worth R550 billion last year while imports, including oil from Angola, were only R180 billion,’ she notes. Under these circumstances, there is a case to be made for these powerhouse economies to liberalise their trade with the rest of the continent much faster.

Hartzenberg notes that this is exactly what Kenya did when the East African Customs Union was established in 2005. It immediately allowed its neighbours’ exports to be allowed duty-free access to its market while allowing them a longer time period (five years) to adjust. ‘Unfortunately South Africa has committed to liberalise at the pace allowed SACU’s weakest member and only least-developed country – Lesotho,’ she points out.

The AfCFTA features ‘variable geometry’, which gives least-developed members a 10-year time frame to open their economies, compared to five years for more-developed economies. ‘We could be moving faster,’ says Hartzenberg. ‘In fact, we should be.’