When Briony Liber was asked about women in mining a few months ago, she said she saw no barriers anymore, except within themselves. But after hearing the starkly contrasting responses of some leading female mining professionals, the Johannesburg-based career and leadership coach made it her mission to dig deeper and explore different perspectives of women in SA mining. ‘I have experienced very subtle discrimination in my career, which in my opinion is a symptom of unconscious bias rather than any malicious intent and never harmed me professionally,’ says Liber, who worked in the mining industry for 18 years before going into coaching and joining the committee of Women in Mining South Africa (WiMSA) – an advocacy group promoting female industry participation through mentorship, training and networking.

‘But having spoken to a lot of women in the last few months, I have become far more aware of how blatant discrimination and harassment can be for some women. How intentionally malicious it can be and how debilitating it has been for some women who work in organisations that structurally do not provide a disclosure mechanism that women feel safe using,’ she says.

In SA, where women have legally been allowed to work underground only since 1996, they are now formal participants in all aspects of the mining industry. Despite challenges and discrimination, their representation has increased significantly over the past two decades.

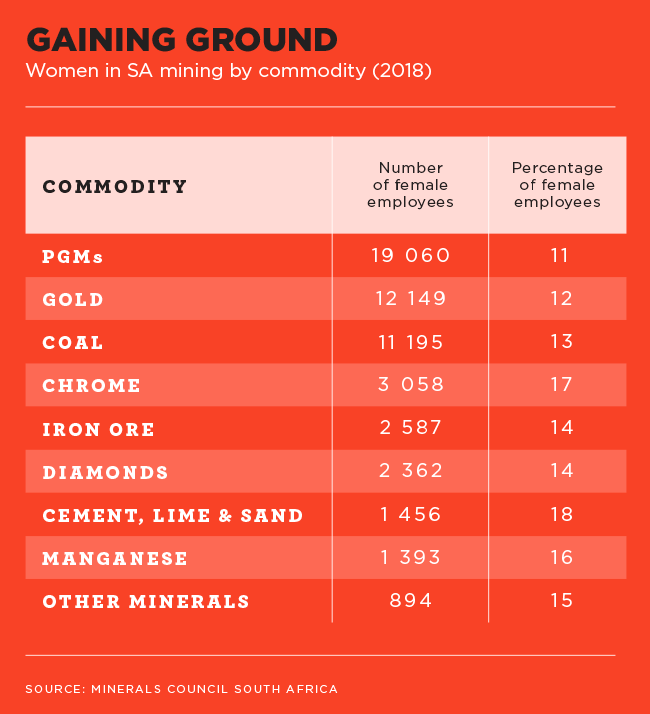

Women make up 12% of the mining labour force of 453 543, according to the latest Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) fact sheet. The sector employed a total of 54 154 women in 2018, up from about 53 000 in 2015 and from a very low base of 11 400 in 2002.

The number of women in top management has grown from 13% in 2016 to 16% in 2018 while female representation in senior management increased from 11% to 17% during this period, and went from 14% to 18% in skilled technical mining jobs. So while the industry is moving in the right direction, a more targeted effort might speed up the progress.

‘The narrative around women in mining is unfortunately one that still requires attention,’ says Thabile Makgala, mining executive at Impala Platinum and WiMSA chairperson. ‘There are still many barriers to entry that women have to overcome. If the environment is not conducive for growth in terms of support, mentorship and infra-structure, females leave the mining industry and join other industries. For those who choose to persevere, being offered the leadership opportunity is a challenge itself, because women are questioned about their abilities.’

In her own career, Makgala pushed past stereotyping and other challenges to become the first female learner official at an SA deep-level gold mine (Gold Fields, now Sibanye-Stillwater) and later the company’s first female regional country head of technical services. This, followed by leadership roles at AngloGold Ashanti, Anglo American Platinum and, most recently, Implats, led to another milestone: being chosen as one of ‘100 Global Inspirational Women in Mining’ from 28 nations.

Having such visible female role models is important, as they can inspire girls and women to not only consider a career in mining but strive for the top (‘if you see it, you can be it’) while also proving to men that competence is gender-neutral.

‘The reality is, until the mindset about women in mining, their competencies and abilities to lead organisations is not questioned, how can we even begin to discuss core mining questions? I believe there is a gap of understanding,’ says Makgala. ‘An unconscious bias that needs to be resolved first.’

And here both men and women play a crucial role. ‘Because people tend to unconsciously gravitate towards people that look and sound like them, in male-dominated environments, women can be unconsciously excluded from activities,’ says Liber, adding that this is also why women often exclude themselves from such scenarios. ‘I know, because have done it myself,’ she says. ‘It takes a lot of awareness to realise unconscious bias is at play and reflect on how this shows up in decision making, in communications, in behaviours and how male leaders in organisations have a role to play in creating safer spaces for everyone to engage.’

Liber advises that one way to control biases is by checking the language you use, reflecting on unconsciously derogatory comments, and by developing an awareness of how your biases show up in your behaviour.

‘I also think men could be better role models for other men – be clear that they don’t accept harassment and discrimination, and hold other men accountable rather than brushing it off as “boys will be boys”.’

In line with this, some mining houses have started with diversity training for their management and workforce. The larger firms run career days and bursary programmes to attract more female talent and offer internal skills and training programmes to develop them. Anglo American takes gender issues further by addressing violence against women in mining. In March last year, the company announced a research partnership in SA with the NGO International Alert. According to Hermien Botes, head of sustainability engagement at Anglo American, ‘the research will help us understand the experience of women at mining operations and in their communities, as it relates to violence and harassment. The aim is to identify potential root causes of conflict, to ensure the safety of women at our operations and work with partners to mobilise against violence in surrounding communities’.

The company was featured on Bloomberg’s Gender-Equality Index for the first time in 2019. The index assesses companies from 10 sectors with a combined market cap of $9 trillion regarding their internal company statistics, employee policies and other initiatives to advance gender equality.

Women in Mining (UK) and EY are currently developing a Global Diversity Index specifically for the mining sector, which will allow local mining companies to benchmark their progress on gender diversity against the global industry. The idea is not to pass judgement but to map and inform stakeholders on how they are doing and which areas require further attention.

‘I would like to see organisations act with real intent and focus,’ says Makgala. ‘This can be achieved through deliberate sponsor-ship programmes, deliberate mentorship programmes and coaching to enable our women to deal with the numerous industry challenges that include structural and cultural barriers. Women on mining committees in organisations should be made compulsory so they can come together to highlight their challenges and come up with solutions on how to overcome [them], and be supported by the leasehold of their organisations.’

More corporates and academic institutions are gradually coming to the table. In August 2019, the Wits School of Mining Engineering Society launched its first Women in Mining chapter. ‘We are working on hosting work-shops with the male generation to do away with patriarchal stereotypes,’ said (male) engineering society chairperson, final-year student Lucas Zulu. ‘Fostering support for women in mining requires a collective effort from both women and men.’

The MCSA is also developing a ‘Women in Mining’ initiative, comprising men as well as women, which is driven by Deshnee Naidoo (CEO of Vedanta Zinc) and Thuthula Balfour (head of health, MCSA). ‘Our purpose is to streamline mining industry strategies to advance women in mining by focusing on increasing women representation and encouraging decisions that are in the best interests of women,’ says Balfour.

‘Two workshops have been held and a survey conducted. An additional survey is currently being developed. The initiative is in its early stages, with the current focus on getting the key initiatives approved by the board. The launch is envisioned for the second half of 2020.’

Liber, who coaches both men and women, advises her clients not to define themselves by gender. She quotes author Kira Makagon: ‘Once on-board, don’t be your gender – be a high-ranking executive. Acknowledge differences and get to work. While gender differences exist, they don’t have to dominate your thoughts or behaviour, or the way you view yourself or others. Instead of identifying as a person confined to your gender role, think of yourself as a human being in a high-ranking role. Recognise universal business skills are gender-neutral.’

This will become even more valid as the future of mining evolves from requiring physical strength to fine motor skills, and issues such as energy and water consumption, carbon emissions and community engagement open up new job opportunities in the industry for female entrants.