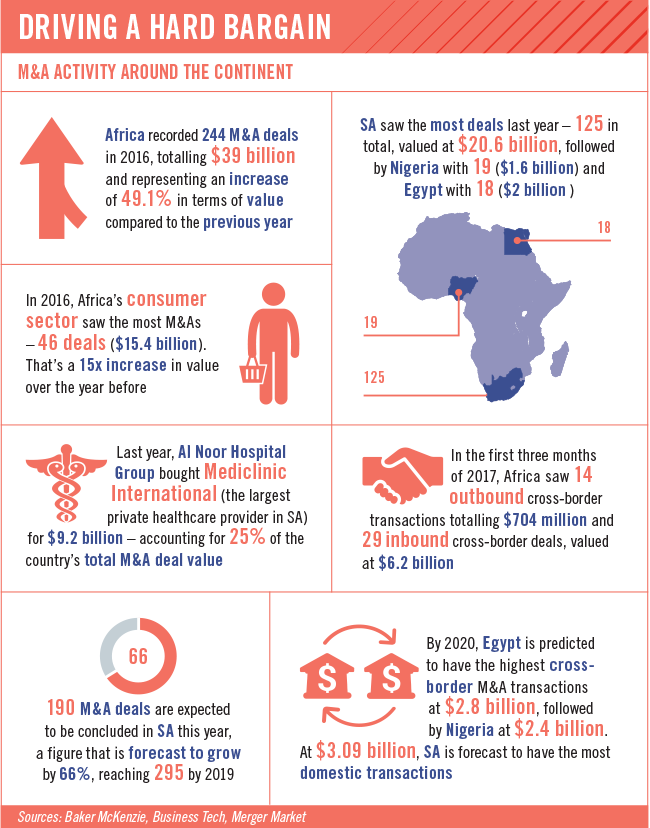

There were 14 outbound cross-border transactions worth $704 million and 29 inbound cross-border deals totalling $6.2 billion in the first three months of 2017 in Africa, according to Baker McKenzie’s first-quarter 2017 cross-border M&A index.

At the same time, the firm – along with Oxford Economics – predicted in early 2017, in the Global Transactions Forecast, that after a year of political uncertainty, a worldwide uptick in transactional activity was likely over the next four years. This is based on a gradual pick-up in global economic growth in the years ahead, with GDP rising to 2.6% in 2017, and 2.8% in 2018. The report states that as threats to the stability of the global economy ease and dealmakers regain confidence in the market, their apprehension (regarding M&As and IPOs) should turn into appetite.

In SA, Sambulo Zungu, partner of M&As at EY transaction advisory services, says the most important aspects that companies wanting to gain a foothold in Africa through M&A activity need to take into account are anti-trust laws of the host country; its exchange-control regulations (particularly when it comes to getting money out of the host-country); the tax framework of the host country, along with its labour, takeover and localisation laws (which, in SA, manifest through BEE); and all sector-specific licensing requirements of the host country.

According to Charles Douglas, M&A head at Bowmans, the key legal challenge for M&As is finding ways to close the com-pliance gap between listed entities outside the continent, and its more informal, family-run businesses.

‘Unlike businesses in developed markets outside Africa, companies on the continent are often privately owned, family-run due to the fact that Africa has fewer and less-developed stock exchanges than places like Europe, the US, Australia and the East, for instance.

‘With the exception of South Africa’s JSE, regulatory standards of bourses in African coun-tries are in varying stages of development, and these bourses are also less liquid than the JSE. The appetite and opportunity among African businesses to list – and therefore to have to consistently adhere to stringent listing and reporting standards – has lagged behind.’

Douglas says the size of M&A deals is generally smaller in Africa than elsewhere – in East Africa, for example, a $150 million deal is regarded as large.

‘Purchasers who want to gain a foothold in Africa by way of M&As must therefore think creatively when they close deals; variations between parties can occur in reporting standards and level of regulation. This is mitigated through tax and environmental insurance while warranties and indemnities are aimed at providing protection to listed businesses that set out operations with partners on the African continent.’

Jan Bouwman, partner at Fasken Martineau, says it’s sound business practice for a party involved in M&A activity to obtain the services both of auditors and legal counsel resident in the African country in which the transaction is to take place.

‘Each African jurisdiction has its own set of laws that pertain to taxes, the environment, competition and so on and, like Canada, the legal systems in Africa are predominantly either Anglo-Saxon or French-orientated, depending on historical factors. Morocco, for instance, derives its legal system from its former colonisers, the French, while Southern African countries are governed by legislation vested in old English law. So too some West African law frameworks. A country’s legal framework plays a key role in the way that the deal needs to be structured.’

Stark differences also occur between countries on the continent in different economic sectors. For instance, permit requirements to enter mining in SA are entirely different from requirements to get a mining licence in Nigeria. Also, terms and conditions to take a workforce in to work the mine would not be the same in any two African countries, hence the need for professional legal counsel and auditors, particularly for advising on the different tax regimes in the different jurisdictions, says Bouwman.

He says the due diligence, whether legal, financial or commercial or a combination thereof, will follow the signing of an MOU between the parties.

‘It’s very important to know that the due diligence is always accompanied by confidentiality clauses to ensure that nothing is disclosed by the acquiring party about the target business even if the deal falls through along the way,’ he says.

In terms of funding, Bouwman says two things are important – how the transaction itself will be funded and, if necessary, how the new venture will be capitalised.

‘Regarding the funding of the transaction, a purchaser could use their own resources or look to funders in either its local jurisdiction or the jurisdiction where the transaction is concluded.’

He says it’s important to bear in mind that certain jurisdictions, including SA, have so-called ‘thin cap’ regulations in terms of which the foreign shareholder of the local company is required to maintain a certain ratio of equity to debt. This means that foreign shareholders will be required by law to introduce a certain portion of the funds themselves, in addition to funds borrowed locally.

‘Regarding the capitalisation of the company, there are obviously numerous options including debt, or raising capital or debt on the markets in Toronto and London, and not often through stock exchanges in Africa, with the exception of the JSE in Johannesburg. This is a result of the relative sophistication of these stock exchanges.’

He notes that in Africa, acquiring parties involved in an acquisition on the continent are able to use a holding company in a tax-friendly jurisdiction such as Mauritius to best structure an acquisition from a tax perspective. This is potentially an effective risk-management tool that allows the inbound business to reduce its risk by cherry-picking only the assets of interest rather than fully becoming the owner in the target business.

Bouwman says the issue of dispute resolution mechanisms is fully dealt with in the contract signed by all the parties involved in the deal.

‘This [contract] document can stipulate that the International Chamber of Commerce is a role player – usually an arbiter – in the event of a dispute occurring. Also, one of the most cumbersome hurdles to overcome in M&As is often obtaining agreement from the parties regarding the jurisdiction in which disputes are to be handled, as parties to deals such as M&As and other transactions are usually not keen to have to subject themselves to courts in foreign countries,’ he says.

Meanwhile, Morné van Wyk, managing partner at Baker Mckenzie, Johannesburg, notes that SA’s recent credit rating downgrades could affect M&A activity in the country.

‘The perception of South Africa as an entry point into the continent and as a destination for medium-to-low risk developing market investment could be hit. However, the rand has shown to be far more resilient than most expected,’ he wrote in an online op-ed piece earlier this year.

‘After a period of sell-offs and volatility, there is hope for a normalisation of the economic environment and a rally of business to restore investor confidence.

‘In the short term, there are expectations that M&A activity will be created by investors withdrawing from the SA market due to the downgrades, voluntarily or as a result of complying with regulatory or policy requirements.’

According to Baker Mckenzie, the global drivers for M&A activity are disruption and technological innovation, after-sales services, core competencies, divestments and defence spending.

As these factors affect the world’s largest economies – especially the Americas, Europe and China – they will no doubt affect M&A activity in Africa too, which is largely influenced through the trajectory of foreign investors.