On a chilly Friday morning in January, Geoffrey Berman, US attorney for the southern district of New York, and William Sweeney Jr, the assistant director-in-charge of the New York office of the FBI, announced that Onyekachi Emmanuel Opara, a Nigerian national, had been extradited to the US from SA to face criminal charges. Opara’s crime? Participating in fraudulent business email compromise scams that targeted thousands of victims around the world. ‘Technology changes daily, so do the tactics used by scammers to prey on unsuspecting victims,’ Sweeney told reporters.

‘This case and others we are aggressively investigating every day prove – regardless of these criminals’ efforts to disguise their illegal activity – we won’t stop pursuing them. FBI New York cybercrime agents and our law enforcement partners will search out suspects in these cases, even reaching internationally, to stop the next victims from losing their money.’

It’s a scene we’re seeing play out more and more as digital technology develops, and as cybersecurity increasingly becomes a global issue. According to a report by the Brookings Institute, the average cost of cybercrime for businesses increased by 22.7% between 2016 and 2017 to reach an average of $11.7 million globally. ‘Incidences are multiplying and escalating,’ wrote report authors Landry and Kevin Signé. ‘The Wannacry ransomware attack in May 2017 hit more than 200 000 users in 150 countries (and more than 400 000 computers) in just a few days. The Equifax data breach in September 2017 may have impacted 147.9 million consumers. These attacks don’t discriminate, either. Companies of all sizes and in all sectors around the world comprise a large majority of cyberattack victims, and this trend is spreading at breakneck speed.’

As Michael Davies, CEO of technology and advisory services company ContinuitySA puts it, although computer hacking started many years ago, ‘the acceleration in technology in terms of connectivity, mobility and a proliferation of devices has led to the evolution of cybercrime and its pervasiveness in society’. And it’s a trend that will only spread faster as digital technologies move towards the ubiquitous internet of things.

‘Internationally we have already experienced attacks against power stations, which successfully brought a region to its knees by not being able to reverse the damage or stop the attack,’ says Maeson Maherry, chief solutions officer at LawTrust, the cybersecurity business of Etion Limited (formerly Ansys). ‘Damage included molten iron solidifying in smelters, resulting in total destruction of the smelter.’

Matthew Purchase, partner at pan-African law firm Bowmans, said in May during a conference at the firm’s Johannesburg offices that cyberfraud was growing even faster than the move to digital.

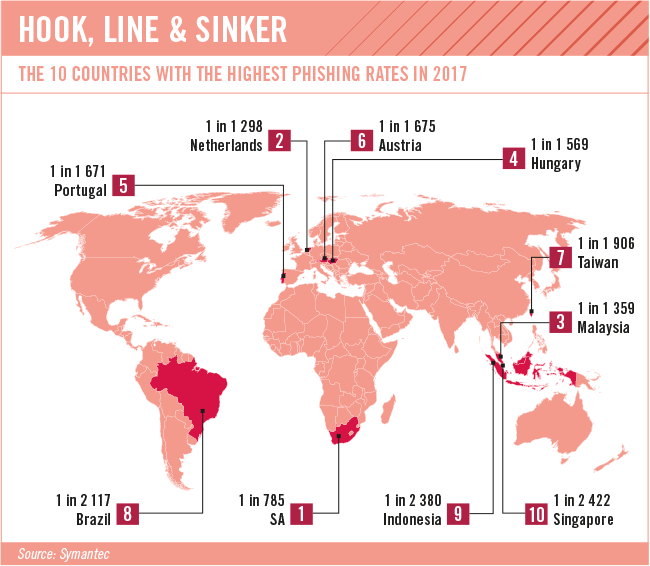

‘According to the FBI, losses from online fraud have grown by around 55%. United Kingdom crime statistics show that one in 10 people in the UK have been affected by online fraud, which is now the most common crime in the UK.’ South Africans, he added, were just as vulnerable to cybercrime – if not more so. ‘The same online fraud trends we are seeing in the US and UK are applicable in South Africa and Africa, and some aspects are exacerbated,’ he said. Part of the problem is that the digital revolution has largely taken place in a regulatory vacuum. ‘In South Africa, we don’t yet have the legislative framework to deal with cybercrime,’ according to Purchase. ‘We have the Cybercrime and [Cyber]Security Bill, but it is not yet in effect.’

Indeed, while the bill was tabled in the National Assembly in February 2017, it has been subject to no small amount of controversy, with legal commentators voicing concerns about its unintended consequences, its over-reach and its effect on other laws such as the Protection of Personal Information Act and RICA. However, as Purchase pointed out, ‘dealing with cybercrime is not only about the legislative framework; it’s also about capacitation and implementation’. There’s a gap, he said, between the law and the difficulty of effectively enforcing it.

Jan-Harm Swanepoel, a senior associate at Adams & Adams Attorneys, highlights this in an opinion piece published on the firm’s website. ‘A question that’s rarely raised is, what will happen to a cybercriminal if he is actually caught?’ he writes. ‘Although it will be extremely tempting to simply lock up the culprit and throw away the key, he will be entitled to the same constitutional rights available to other arrested persons to dispute the allegations against him.’

In echoes of Opara’s case, Swanepoel raises the question of what might happen ‘in the likely event’ of an accused cybercriminal committing an offence in more than one country, with extradition proceedings then coming into play. (And, let’s face it: if you’ve ever received a so-called 419 scam email from a Nigerian prince offering you a share of his inheritance, then you’ll appreciate the cross-border implications.)

‘Even if an accused is arrested on the strength of an arrest warrant issued for purposes of extraditing him to stand trial in another country, he will still be entitled to dispute the extradition order and may even be granted bail while doing so,’ writes Swanepoel. He cites the 2016 case of Patel versus NDPP, where the accused was arrested in SA in 2011 pursuant to a request for extradition from the US, after a warrant of arrest was issued for him. Mr Patel fought his extradition all the way to the Supreme Court of Appeal [SCA], where his appeal was eventually dismissed in 2016,’ he states.

Swanepoel adds that while the facts and technical arguments raised by Patel’s legal team were interesting on their own, the really interesting part came when Patel’s appeal was eventually dismissed in the SCA, after he had already been out on bail for several years. ‘Although I stand to be corrected, I doubt Mr Patel merely shrugged his shoulders and reported to the authorities to catch the next flight to the US when he heard that the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled against him,’ he writes.

The Patel case is one of many like it. ‘There are several examples of accused persons being granted bail and delaying extradition proceedings to frustrate the authorities,’ Swanepoel adds. ‘Therefore the state will need to ensure that its house is in order already at the very inception of this matter, especially if one considers the intelligence of and resources at the disposal of “hackers”.’ Legislation, of course, ‘can only go so far, people and organisations need to take the initiative to mitigate their risks relating to cybercrime’, adds Davies.

According to Graham Croock, director at BDO’s IT advisory and cyber lab, cyberattacks have become the order of the day, and it’s a threat that SA executives don’t take seriously enough. ‘Having seen the level of sophistication associated with the attack vectors and methodologies, I have no doubt that most South African businesses must now accept that it has already happened to them,’ he says. Croock adds that hackers are creating attacks designed to go undetected by traditional antivirus products, in order to monetise their efforts. ‘Traditional endpoint protection is only effective in protecting against known malware.’

The emergence of blockchain technology, however, appears to be a promising move towards safer digital transactions. ‘What has made blockchain a world-wide craze is the understanding that the system is secure from alteration and cheating,’ says Maherry. ‘This concept, known as immutability, is achieved by applying encryption. Cryptocurrencies have flourished because of the blockchain’s ability to disintermediate, create transparency and commit irreversible, secure transactions.’ Maherry adds that LawTrust is currently involved in blockchain security research for a secure cryptocurrency wallet, which would take the form of a USB token unlocked with the user’s fingerprint. ‘While blockchain has its role to play where problems require a distributed ledger solution as an answer, the fundamental technology components of blockchain that provide security and immutability can also be used independently of the blockchain,’ he says. ‘Building blocks – like digital signatures for immutability – can be added to information systems such as payroll, ERP [enterprise resource planning] and even mainframe systems. This, combined with strong authentication, can protect the investment already made in a business system and extend its useful lifespan to the business.’

Maherry is quick to add that while cybercrime may get a fair amount of hype, no organisation can afford to underestimate its importance.

‘Cybercrime is a definite reality,’ he says. ‘It ranges from hacktivists lashing out, to hardened criminals taking or extorting money, right through to nations attacking each other, with collateral damage affecting companies and individuals.’ Considering global lifestyles and business environments are heavily digital, you have to – as he puts it – be streetwise and protect yourself and your business.

‘You wouldn’t walk through a dark alley in a bad neighbourhood at night wearing a gold Rolex on your arm, as you know and manage the risks,’ he says. ‘You need to think the same in the cyber neighbourhood.’