There’s a glimmer of hope and even occasional glimpses of excitement amid the bleakness of mining job losses and difficult restructuring processes. The ‘upskilling’, ‘reskilling’ and ‘skills-transfer’ initiatives for existing mine workforces don’t necessarily take them back to study in a typical teacher and classroom scenario.

Many of those currently working in traditional, physically demanding underground jobs who require new skills as they move to safer, more modern and less arduous ones are being taught through gamification, virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). ‘We can take you to any place and any time,’ says Business Science Corporation (BSC), a Johannesburg-based data science and technology implementation firm, about its VR solutions.

In mining, VR can virtually transport people into underground and surface environments, simulating rock falls, fall-of-ground events and even rock-blasting situations. It is used to train artisans and equipment operators, and for safety training of entire workforces, including management. ‘Gamification is really coming into play now,’ says Johan Bouwer, head of VR and new technology at SA tech company Simulated Training Solutions (STS3D), which serves more than 50 corporate clients in 15 countries, including Glencore International, Anglo American, BHP Group, Harmony Gold, Impala Platinum, Aquarius Platinum, Sasol, Samancor Chrome and Murray & Roberts.

He explains that when the training gets turned into a game, it helps employees grasp complex topics – and possibly even enjoy the learning process. ‘We write games that the user can play to start understanding any subject matter and learn the things that are necessary to do the job safely and correctly,’ says Bouwer.

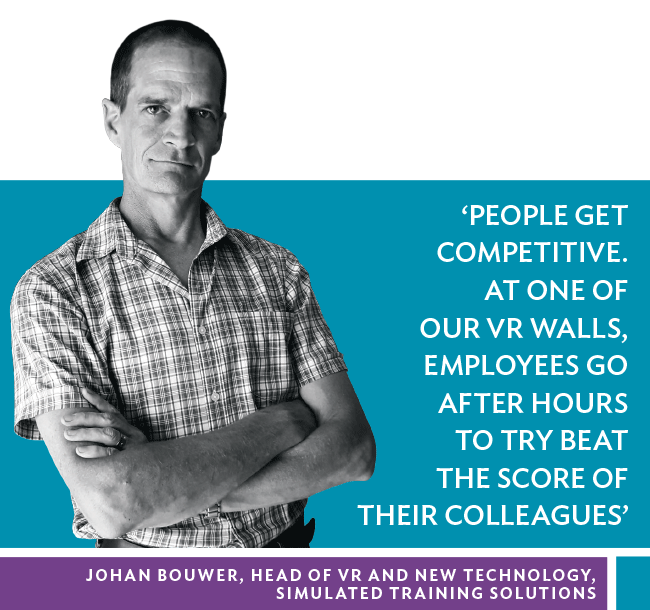

‘We include certain competitive elements to entice them to practise, because it’s far more effective to be intrinsically motivated to train as opposed to extrinsically. We found that people get competitive. At one of our VR walls employees go after hours and on weekends to try beat the score of their colleagues.’

STS3D developed the world’s first VR blast wall (as well as a locally-made VR cube) to train and assess miners on the correct way to blast rock – in a significantly safer, more cost-effective and time-efficient way than a real-life situation would allow. The wall uses infrared emitters, projectors and computer graphics to simulate the ‘marking, drilling and blasting’ of the rock. The miners who are immersed in this training don’t need to wear the typical VR headgear while they mark the rock face, time the holes, blast the wall and fracture the rock.

The VR cube enables audience viewing and interaction, allowing the instructor to observe the trainee during the training. It’s similar to the highly realistic mine experience created for the Kumba VR Mine Design Centre at Pretoria University, in which STS3D is the strategic partner. ‘It’s an impressive experience that builds muscle memory,’ says Bouwer. ‘The trainees actually become involved and do the exercise in a completely safe environment, comparable to pilot training in a flight simulator. By the time they get to the real-life situation, they recall everything because it’s an experience they’ve gone through, rather than merely watching a video or being lectured by an instructor.’

In 2018, STS3D installed the world’s first underground VR blast wall (measuring 8m wide by 2m high) at Glencore’s Thorncliffe chrome mine in Limpopo. This comes two years after the firm built the first surface VR wall at Glencore’s Mopani Copper Mines in Zambia, which was followed by two more VR walls in SA: at Anglo American Platinum’s Tumela mine in Limpopo and the Murray & Roberts Cementation Training Academy (MRTA) near Carletonville. ‘We have invested in this technology because it can improve the performance of the learners in our three key priority areas, to achieve a daily, safe, quality blast,’ says Tony Pretorius, MRTA education, training and development executive. He explains that the VR blast wall ‘is designed to teach workers practically how take line and grade, mark off the blast pattern and burden, and time the round to ensure the correct [safe] firing sequence’.

The blast wall augments the training academy’s blended learning approach, which combines the use of integrated e-learning programmes and inert explosives. According to Sietse van der Woude, senior executive: modernisation and safety at the Minerals Council South Africa, modern teaching technologies and methods are enabling people to train on a far more modular and flexible basis than conventional training. Another advantage is significant cost savings through online delivery. ‘Further, technologies such as virtual and augmented reality provide learners with the opportunities to develop specific skills, without needing massive investment costs into infrastructure or equipment,’ he says. ‘Access to knowledge and the development of skills will therefore increase dramatically in future, while also seeing a relative fall in the cost of such education – the result being the opportunity to rapidly and constantly close skills gaps. The mining industry is taking account of this and is experiment-ing, with significant effort being put into training through virtual reality simulators and gamified systems to help teach employees a range of skills.’

While VR has shown to increase the retention of content, it also exposes areas that still require more training. ‘Our experience with all learners thus far has indeed been a revelation,’ according to a training manager at Gold Fields’ South Deep mine in a testimonial for BSC. ‘Not only did it expose major gaps in our traditional ways of training but also revealed without doubt that some people do not even understand the basics.’

VR can also help identify basic problems that otherwise might be detected only after lengthy training. Steel and mining company ArcelorMittal is using the technology in its internship and training programme at its Vanderbijlpark works to establish whether a new recruit will be able to work at heights. With the help of Sea Monster, a local animation development studio, the company has introduced a VR solution that recreates working at a height of 190m.

To make the conditions realistic, fans simulate the wind while a raised platform and vibrating plates mimic the movement of the lift. Prospective employees have to complete three tasks, designed to gauge their cognitive performance, while their physiological responses are monitored and they are screened for colour blindness. ‘Several trainees have already been identified as having a fear of heights and have been reassigned to other positions within the company,’ according to Sea Monster. ‘Expected results for the future include significantly reduced number of injuries and accidents on site.’

VR is particularly useful for safety training. Accidents can be reconstructed to explain the chain of events and help miners learn from real-life incidents. On the other hand, bite-sized interactive VR experiences assist in entrenching safer behaviour, because users can experiment and make mistakes on screen without risking personal injury or damage to equipment. This is also crucial when it comes to reskilling miners and training competency for using new machinery. ‘In VR we have a vehicle where you walk around that virtual machine and learn about all the danger points,’ says Bouwer. ‘Once you’ve done the training, you’re completely familiar with the machine so there’s minimal risk of getting injured, breaking something or injuring someone else.’

VR is also used to create engine assembly and repair simulations to teach trainees about the different components and how they fit together. Modernisation and automation may initially seem daunting to existing employees. Yes, it generally requires a more tech-savvy workforce than traditional mining. But Simon Andrews, vice-president of sales for Southern Africa at Sandvik Mining and Rock Technology, says that ‘with thorough training, any individual who is able to read and write can operate a machine remotely’.

As he told Mining Review Africa, ‘a simple four- to six-week training session is generally sufficient for an individual to develop a competency level necessary to operate an automated machine. Hand/eye co-ordination and relearning to operate a remote that is not sensitive to touch are in fact the greatest challenges’. Here VR technology can help bridge the gap between traditional and modern mining. ‘We pitch our training so people understand what they need to learn,’ says Bouwer. ‘A lot of our client base is [aged] 45 years and older, with very limited education and not computer literate. So we wrote a programme that teaches computer skills by means of a soccer game. After playing, you’re able to complete a multiple choice on the interactive screen.’

As skills requirements change in mining, the training methods are also advancing. When done correctly, they have the potential to turn SA’s challenging skills situation into a more manageable one.