Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, SA Minister of Finance Pravin Gordhan remarked that there is ‘all this money sloshing around the world. The problem is that there’s not enough confidence to invest. The task is to build confidence’. In other words, there is in fact ample money looking for returns.

In Africa, resources is no longer the dominant opportunity sector it has been since about 2000. But the property, tourism, education, health, retail, manufacturing, ICT and agriculture and agroprocessing sub-sectors all offer value. Many of the continent’s big infrastructure programmes have taken off, with about $70 billion having recently gone into this area.

African countries are increasingly and correctly differentiating themselves. This makes a mockery of the simplistic Africa optimist/pessimist dichotomy. Indeed, 2016 is the year of the Africa realist. It is time to assess what looks good and where the opportunities lie.

The dramatic drop in the oil price over the past year has coloured views of the continent, arguably too dramatically. It is certainly bad news for the eight oil-exporting nations in Africa. They are going to struggle to meet fiscal commitments and, in some cases (Nigeria to the fore) this may well generate political crises. According to Bloomberg, Nigeria faces a ‘fiscal gap’ of $15 billion and IMF MD Christine Lagarde, on a recent visit to the country, said that this reduces ‘the space for policy interventions to address social and infrastructure needs’.

The same problems confront the other oil exporters: Angola, Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea and South Sudan. Add security threats (including Boko Haram and other fundamentalists active across the Sahel and East Africa), talk of declining Chinese demand for commodities, rising national debt levels (notably Ghana) and there seems to be a case for the pessimists in 2016. But if this is true, why do the World Bank and IMF still predict healthy growth for much of the continent in 2016?

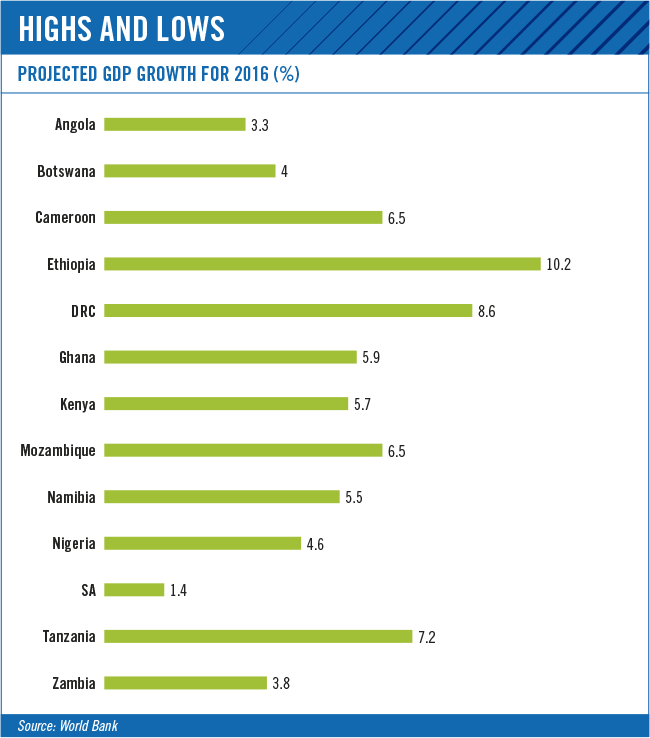

The IMF expects Nigeria will grow at 4.1% in 2016 and the World Bank’s projections for other key African investment destinations are little short of spectacular – Ethiopia 10.2%, DRC 8.6%, Tanzania 7.2% and Kenya 5.7%. The World Bank’s overall projection for sub-Saharan Africa is 4.2%. This may have slipped from the 5.7% the bank says the continent averaged between 2000 and 2010 but it’s certainly not too shabby.

Ronak Gopaldas, head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank, argues that ‘the latest commodity crisis has exposed Africa’s vulnerabilities’. In some cases, he adds, there have also been ‘policy own goals’. Buoyant commodity markets meant that governments did not have to work on what have now turned out to be necessary reforms – more liquid financial markets, policy certainty, tapping external funding sources and a push towards greater diversification, he says.

In any case, the continent-wide figures hide some significant variations. Martyn Davies, MD of emerging markets and Africa at Frontier Advisory Deloitte, argues that oil importer/exporter divide also corresponds to an East/West Africa distinction. ‘There is a rapid shift of gravity of growth on the continent, from West to East Africa,’ he says.

The fact is, there are still enormous and expanding business opportunities on the continent. Some of these are in little-explored areas.

In 2015, there were nearly 1 million candidates for Kenya’s primary certificate, the KCPE, awarded for passing a competitive exam after seven years of schooling. Opportunities for private academies, tuition, kindergartens and school suppliers abound.

Kenya looks especially promising in 2016. Its budget is not linked to oil prices and China is not one of its main export markets. All forms of property development – residential, industrial, commercial, retail and hotel – have surged in recent years. New buildings in Nairobi alone were valued at $600 million in 2013 – and the boom goes on. The value of a bungalow house in Nairobi has increased by more than 400% since 2000 and demand still exceeds supply. As Nairobi becomes saturated, attention is expected to turn to the city’s dormitory towns – Ruaka, Thika, Kitengela and Ongata Rongai.

The East African country’s property boom is directly related to infrastructure investment. Its investment in energy generation, especially renewable, has been widely reported but other projects are also significant. The 50-km long, 12-lane Thika highway aims to ease Nairobi’s traffic congestion by offering a southern bypass. Parts of the motorway are already open, although construction of some sections has been lagging. The growth of Nairobi’s dormitory towns, of course, also offers opportunities in municipal infrastructure: water, sanitation and electricity reticulation.

Gopaldas agrees that East Africa looks more attractive in 2016 than the oil export-dominated West. Kenya’s role as a regional investment hub and point of entry is important. He recommends, however, that other regional economies, especially Tanzania, should not be ignored and notes that its new president, John Magafuli, is generating a great deal of excitement. ‘He is a reformer who may make a big difference to the quality of governance in that country,’ says Gopaldas. ‘He appears committed to all the things investors want to see.’

Rwanda too has made startling improvements in its business climate and is now bettered in Africa only by Botswana and Mauritius. However, business-climate indicators should not be over-emphasised. It is often pointed out that Rwanda scored better than Italy in aggregate Doing Business in 2016 indicators. This is good for Rwanda but it refers only to the quality of economic regulation. It would be foolish to think there is more business opportunity in Rwanda (with its 2014 GDP of $7.89 billion) than Italy, where GDP was $2.141 trillion.

Gopaldas points to another little-remarked high-growth candidate: Côte d’Ivoire. Having come through two civil wars since the millennium, Côte d’Ivoire has demonstrated stability over the past five years. Its president, Alassane Ouattara, former deputy head of the IMF, is committed to investor-friendly policies and hopes to ‘crowd in the private sector’.

Another East African country, Ethiopia, is at the leading edge of a different opportunity vector. Its move into manufacturing has attracted attention. As China has developed, its labour and other inputs have become pricier. The Chinese yuan is no longer pegged artificially low, and thus the country’s exchange rate can no longer offer the sort of dramatic competitive advantage it did before it was allowed to ‘float’ in 2009. Chinese manufacturers are actively hunting for offshore manufacturing locations where conditions are more favourable.

Many of these are East Asian – in particular Vietnam and Cambodia – but the move has opened up Africa’s prospects and the continent is very much on the map. China is officially ‘in transition’ (between a manufacturing- and services-based economy) and the uncertainty has generated much negativity in global markets. But the country is still growing at around 6% per annum so it is difficult to give the doomsayers much credence.

Indeed China’s transition is still considered a clear opportunity for Africa to get into Chinese (and other) manufacturing value chains at levels above that of raw materials supplier. A Chinese business representative, addressing the forum in Davos, pointed out that around 5 million Chinese manufacturing jobs would be relocating to lower-cost environments, and that there were African countries that were well positioned to capitalise.

In Ethiopia, this is official policy. Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn has argued that China is easy to do business with (‘the best I have known’). He pointed out that the transformation of Ethiopia’s leather industry into shoe manufacturing was already under way as an example. Ethiopia has 30 large-scale leather tanneries and literally hundreds of footware factories, many well established and small-scale. But the big international players are investing. Chinese giant Huajian – which manufactures footware for US brands such as Guess and Calvin Klein – is in the process of investing some $4 billion in the industry.

Davies points out that Ethiopia has grown at an average rate of 10% for the last decade. It has invested enormously in infrastructure, spending 19% of GDP in this sector in 2011, the third-highest rate in the world. This includes the continent’s largest hydroelectric dam, the 6 000 MW Grand Renaissance, as well as other energy, transport and water projects.

Davies says Ethiopia’s approach reminds him of the Chinese model: ‘economic reform with strong centralised political control’. One result of this control is a quiescent workforce with trade unions being effectively outlawed. Ethiopia is no-one’s dream of a liberal democracy but it does offer opportunities. He adds that tax incentives are available for high-priority sectors, including tourism, agroprocessing, leather and leather goods, manufacturing, textiles, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, minerals and metal processing.

What is currently true of the oil exporters – that the resources crunch raises their potential for fiscal and thus political disaster – is not true of those who have to import oil. Some of 2016’s investment hot spots – Ethiopia, Tanzania and Kenya – fall into this category. But even the oil exporters have real growth potential in 2016. Among major countries, the only real laggards are a few of the middle-income economies that have made poor decisions in recent years, notably SA, Zambia and, to a degree, overspending Ghana.

This does not mean that 2016 will be an easy year. It is not for nothing that the IMF titled its October 2015 preview Dealing with the Gathering Clouds. But clouds, of course, bring rain – and that makes it a good moment to ask where in Africa the seeds of growth have already been planted.