Women are more likely than men to be lumbered with thankless office chores – or what four female US academics call ‘non-promotable tasks’ (NPTs). These are time-consuming tasks that need to be done but are not central to the company’s mission and don’t get rewarded by bosses, such as taking notes in meetings, onboarding a new staff member, screening interns, organising the year-end function, or helping others with their work.

In a recently released book titled the No Club: Putting a Stop to Women’s Dead-end Work, the four academics explain how female employees are disproportionally asked and expected to perform NPTs – essentially ‘housework’ at the office. This creates a gender imbalance that often leaves women over-committed, as their head space, energy and time is diverted away from their promotable work. As a result, they aren’t properly able to display their talent and value to the company, which could lead to their career advancing more slowly than that of their male colleagues. Many high-potential women become stuck in middle management, despite having the skills and ambition for a C-suite corner office.

To change this gender imbalance, the authors offer suggestions on how women can say no to taking on this type of work without burning bridges, and focus fully on building their careers. But that’s not enough, argue the authors; companies also need to change how they allocate NPTs to utilise their female talent better, which often has the added benefit of enhancing the organisation’s own productivity and profitability.

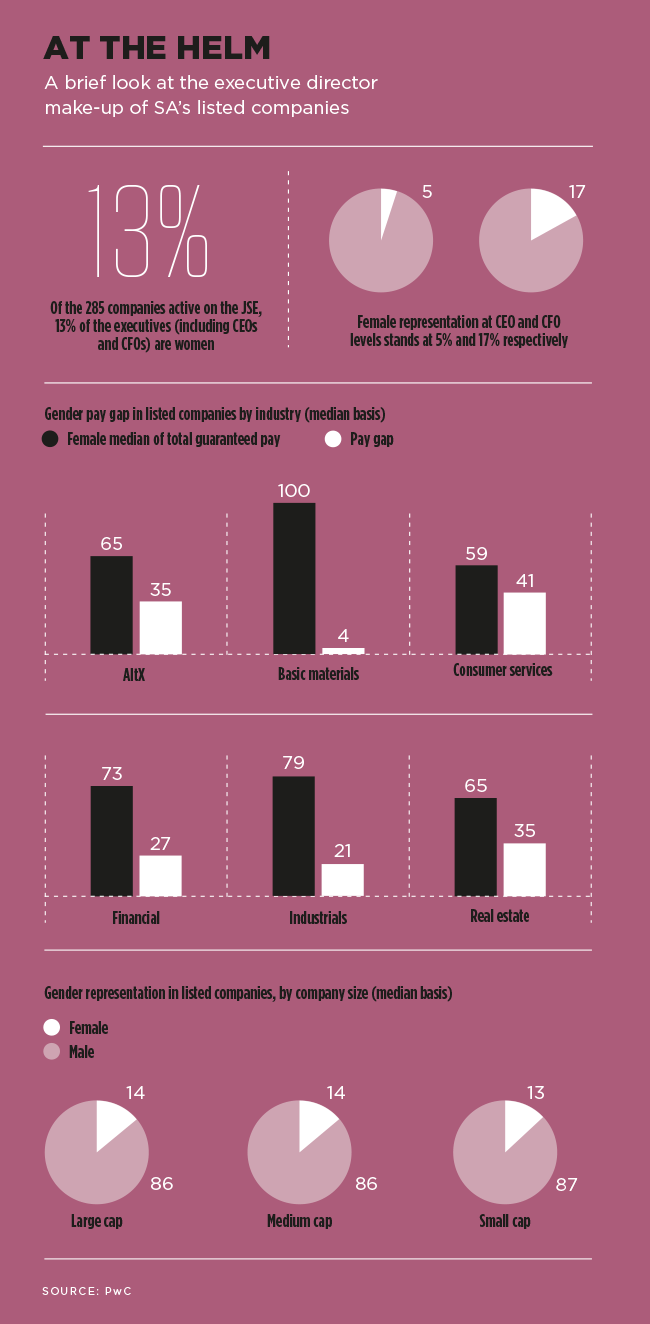

There are, of course, many other factors why female professionals can’t easily move from middle to senior leadership roles. Anita Bosch, research chair for Women at Work at the University of Stellenbosch Business School, reiterates the importance of having more women in executive and board positions, and encourages directors, institutional investors and shareholders ‘to think deeply about how they use their influence to ensure that boards benefit from the richness of thinking that comes with gender and racial diversity’.

SA listed-company boards have become more gender diverse, the proportion of women on boards having increased from 12.6% in 2008 to 26.9% in 2021, according to Bosch’s latest report, which explores trade as a catalyst for board gender diversity. This percentage is low compared to listed companies in Europe, where Iceland’s boards have almost reached gender parity (48.9% female), and even the worst performer, Portugal, has slightly more women on boards (28.1%) than SA.

‘Women’s continued low levels of representation in senior executive roles in South African companies continues to hamper their chances of becoming executive directors, and they are commonly appointed as non-executive board members,’ says Bosch. Furthermore, women face a ‘second glass ceiling’ because, once appointed to a board, they are unlikely to become chairs of the key board committees for audit, nominations and remuneration.

‘Significant power and responsibility vests in these committees, especially in those chairing them,’ she says. ‘Studies show that higher female committee representation is reflected in companies having fairer remuneration policies, financial reports of higher quality, and more diverse appointments to boards. Yet, South African companies are struggling to improve on women chairing these committees.’

One way of addressing the bottleneck in women’s careers between middle and senior management is through specialised training and coaching that focuses on female leaders, as well as those working with them.

‘We are finding a trend towards in-company programmes, and have run our Gender Identity in Leadership programme for a number of companies and SETAs,’ says Zanele Ndaba, a senior lecturer at Wits Business School (WBS), who developed the course based on the school’s former Women in Leadership programme. ‘In 2020 we felt that, in keeping with global trends, the time was right to broaden our offering to focus more on gender issues in the workplace.

‘We recognise that women have more than one identity, beyond traditional stereotypes, and that there is a need for training in how to manage diversity in the workplace and to encourage a greater understanding of gender identity,’ she says.

‘This is a very important element of overall leadership development. The programme is targeted at middle to senior management; people who want to fast-track their careers into executive positions. Our delegates are mostly women, but we would like to move to a situation where we have much more representation from men – this would add an important dimension to the dialogue and learning experience.

‘In essence, we don’t want to “preach to the converted”, and if more men still hold the majority of senior leadership positions in South African organisations, that should be reflected in our leadership programme enrolments, including gender identity.’

WBS offers an MBA elective on gender identity, and Ndaba believes there is room on MBA courses for an entire stream on diversity and inclusion management. ‘Gender issues should and will become more mainstream in management education,’ she says, adding that there is also still a place for Women in Leadership programmes. WBS runs ad hoc courses for industry, such as women in water and sanitation, or executive women in the nuclear-energy sector.

‘Giving women a safe space to talk with other women allows them to raise issues that maybe wouldn’t come up if there were men in the room. It creates a different dynamic,’ says Jenny Boxall, co-convenor of the Developing Women in Leadership (DWIL) programme at UCT’s Graduate School of Business. ‘We focus on key skills that we have identified as touchstone points, such as self-awareness, leadership presence, building relationships and networks and, crucially, understanding the organisational environment – learning how to navigate organisational power, and politics and gender issues. One of the key outcomes for the delegates is developing the confidence to speak up – to know what issues they want to talk about at work and then how to raise them, to get seen and heard. Ideally, they need to do this in a receptive environment. So yes, the way to develop that receptive environment could be a broader process that includes men.’

The feedback from participants is very positive, with some visibly more confident than when they started, and many stating they now have the courage to ask for what they want, as for instance, a salary raise. For this to happen, women need to develop greater self-awareness, awareness of others, and a habit of reflection and conscious learning. ‘One thing that the women say is that when they started on the programme, they didn’t expect to experience such a powerful inward journey,’ says Makgathi Mokwena, an arts therapist, leadership development expert and DWIL co-convener.

‘Some of the women have lost sight of what they can develop within themselves and become outwardly focused, which means they’re not necessarily asking what are the obstacles that lie within, and also not what magnificence lies within.’

Through coaching circles, women bring in real-life issues, express emotions and build relationships, according to Mokwena. ‘Sometimes at work, we feel that aspects of the self have to be cut off. But if we can’t practise being our whole selves, how do we lead with authenticity? Companies need to start accepting women who show up in their full selves and don’t necessarily fit into a particular norm. This is what authentic leadership looks like.’

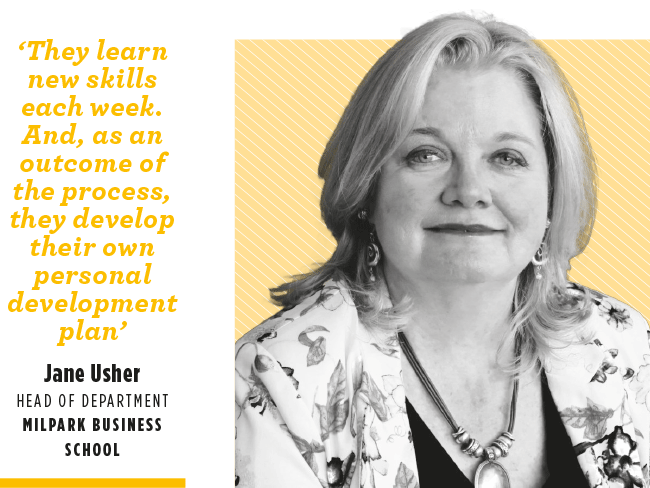

The COVID crisis has added significant pressure on women, which is now being reflected in management training. ‘Post-pandemic, one of the main challenges for women is having to navigate work-life integration,’ according to Leigh-Ann Hayward, chief commercial officer at Milpark Education. ‘Our Women in Leadership programme provides them with tools to regain greater work-life integration and balance. At this stage, our focus remains specifically on women to make up the ground lost during COVID in reaching the UN Sustainable Development Goal number five, gender equality.’

Jane Usher, Milpark Business School head of department, explains that the course is designed as a ‘learning journey’ in which, as participants ‘move step by step through the process of discovery, they learn new skills each week. And as an outcome of the process, they develop their own personal development plan, with timelines, activities and goals that they can follow’. This plan, she says, ‘is useful for their personal development plan at work, and we encourage them to consult with their line managers to explore the ways of gaining the new skills they need through the organisation’s learning and development programmes. So, the programme works on a personal as well as professional basis’.

While women can work on their self-development and inward journey, there are ways in which companies can help in smoothing the move from middle to senior management. These range from technical and professional training, mentorship schemes and flexible working arrangements, to gender diversity and inclusion policies – and not to forget the fairer allocation of NPTs. After all, unburdening high-potential women from thankless office chores can free them up for greater things.