SA’s mining sector burnt bright as a lone flame of hope in the darkness of the recent pandemic years. In the words of the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA), the sector ‘bailed government, the fiscus and the economy out of two years of COVID-19-induced economic slowdown, enabling the continued payment of social grants and debt reduction’. That light has started to dim again, owing to infrastructure issues and other constraints beyond the industry’s control, but the future could still be bright.

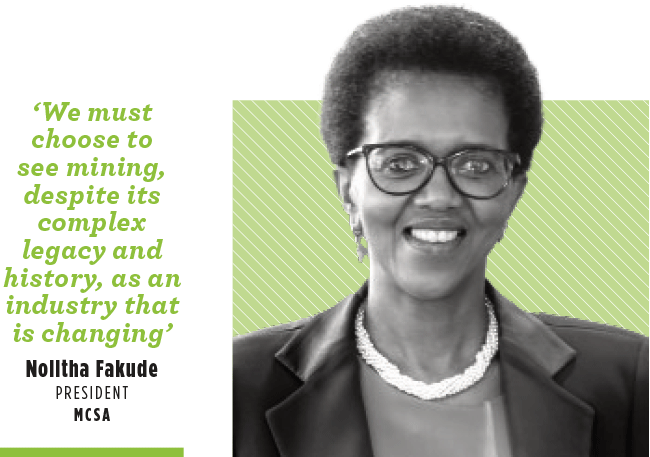

Mining has the potential to become the country’s ‘lighthouse’ industry and has the natural resources to lead the world in its transition to net zero carbon emissions, according to Nolitha Fakude, president of the MCSA and chair of Anglo American’s management board in SA.

‘With climate change and the global energy transition well under way, it is many of the metals and minerals we produce right here in South Africa that are required to support this transition – and our abundant sun and wind resources give us yet another wonderful opportunity to produce and benefit from renewable energy sources,’ she said in her keynote address at the Joburg Indaba in October 2022. ‘Not only would we catalyse the much-needed growth and socio-economic development that our country so desperately needs, but we would also create a pathway and model for other industries to follow suit while helping South Africa’s own decarbonisation journey as we, together, fight global climate change.’

However – and there’s a big ‘however’ – Fakude also clearly outlined the many challenges and constraints that are stunting the sector. ‘We are at the intersection between hope and despair,’ she said.

Hope stems from ‘green metals’, the renewable energy potential, and what Andries Rossouw, Africa energy, utilities and resources leader at PwC Africa, describes as the mining sector’s ‘sterling performance’ over the past year.

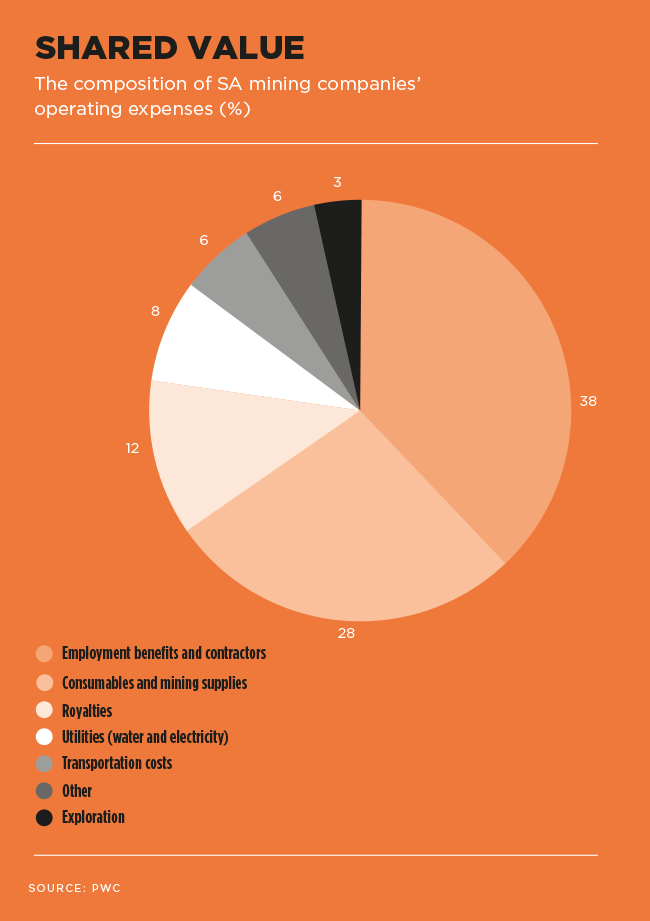

‘The industry’s financial performance exceeded expectations on most fronts,’ he says in PwC’s Mine SA 2022 report. ‘Distributions to shareholders more than doubled to R190 billion, capital expenditure grew by 36% and taxes paid increased by 14% as South African mining companies in aggregate maintained profitability at last year’s high levels.

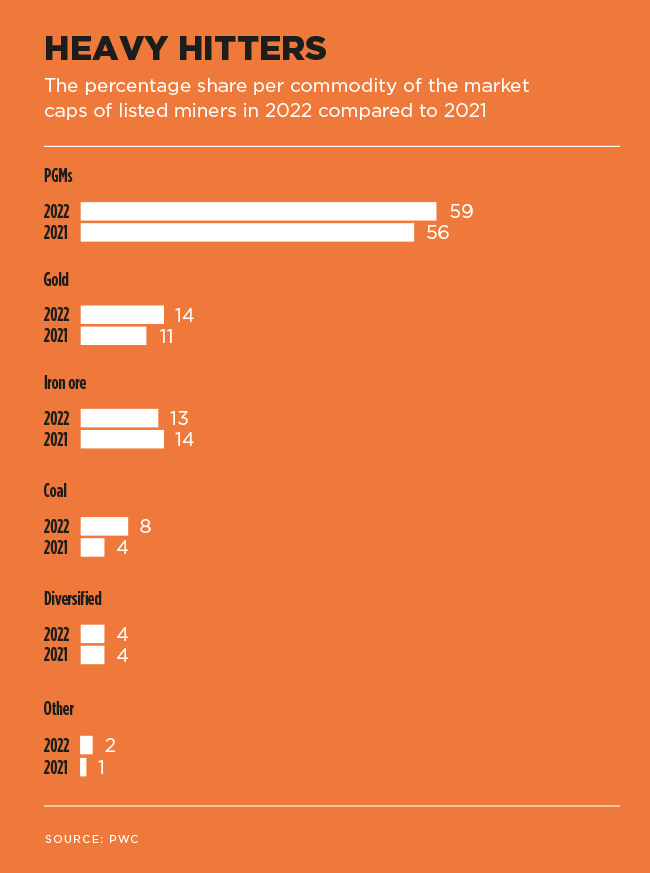

‘Growing demand for commodities saw record rand prices for the platinum group metals basket, iron ore and coal, while most other South African commodity prices remained at relatively high rand levels.’

SA’s mineral production in 2021 reached an historic high. Valued at R1.19 trillion (up from R910 billion in 2020), it was driven by the high commodity prices, according to the MCSA. The export value of minerals increased from R577 billion in 2020 to R842 billion in 2021. The total interim exports showed that in the first half of 2022, value was up but volumes were down. A number of constraints mean that, despite record prices, production is stagnant and export volumes declining. But before looking into the issues that constrain the sector, one should review those that inspire hope.

Fortunately, employment in mining remains steady at an average of 460 845 jobs in 2022, compared to 459 945 in the 12 months to end-June 2021. Furthermore, SA’s world-class mining sector has more than R100 billion in private-sector investment in renewable-energy projects. And, importantly, the country’s significant mineral resources feature more than 80% of the world’s known PGM reserves, in addition to other minerals critical for the decarbonisation economy, such as zinc and manganese. Nickel and copper are both by-products of PGM mining. The global demand for ‘green’ or ‘transition’ metals such as these is only going to rise further, seeing as they are essential ingredients in all of the clean technologies required to limit global warming – from wind turbines and solar PV, to electric vehicles and battery storage.

PGMs also are integral to the green-hydrogen economy, which seeks to replace fossil fuels and feedstock (coal, oil, diesel, jet fuel and others linked to global warming) and decarbonise multiple economic sectors.

‘Platinum, ruthenium and iridium are used to make proton-exchange membrane electrolysers,’ according to Allan Seccombe, MCSA spokesperson. ‘Platinum is used to make fuel cells. Platinum, palladium and ruthenium are used to make catalytic converters. The combination of green hydrogen displacing natural gas, and fuel-cell electric vehicles displacing internal combustion engine vehicles, could result in net CO2 savings of up to 11% of the Paris Agreement’s 2030 targets,’ he adds, referencing data from the World Platinum Investment Council.

‘Annual platinum demand in 2030 from fuel-cell electric vehicles and electrolysers of between 1.6 million oz and 2.4 million oz provides a growth opportunity for South Africa of between 34% and 51% by 2030 from the current 4.7 million oz base.’

SA’s hydrogen roadmap, launched in early 2022, is a vital step in the just energy transition to a sustainable, low-carbon and equitable future. Anglo American, together with the Department of Science and Innovation as well as private partners, has been driving the development of the Hydrogen Valley, which will link the Mogalakwena platinum mine in Limpopo to Johannesburg and Durban. Through the Rhynbow project, for example, the partners want to aggregate demand for fuel-cell heavy-duty vehicles, including buses and articulated trucks, to scale a viable operational ecosystem. Amplats made the start by introducing the world’s biggest green hydrogen-powered haul truck, weighing 220 tons (saving about 3 000 litres of diesel a day).

‘We plan to retrofit 40 diesel-powered ultra-class haul trucks at Mogalakwena to hydrogen, before rolling out the technology across our global fleet of around 400 trucks,’ says Amplats CEO Natascha Viljoen. ‘With haul trucks representing up to 80% of diesel emissions at our mine sites, this technology will make a major contribution towards our operational carbon neutrality target.’

David Walwyn, professor of engineering and technology management at the University of Pretoria, highlights another local hydrogen initiative that has the potential for global impact – Sasol’s sustainable aviation fuels could help develop SA as a hub for affordable, green fuel for commercial airlines. ‘Aviation presents one of the most challenging sectors to decarbonise, and there is little chance that long-haul flights can be made using either batteries or hydrogen. Liquid fuels, and particularly green fuels, are the only realistic option in the medium term.’ Walwyn considers SA’s synthetic fuels experience with Fischer-Tropsch (gas-to-liquid) technology to be invaluable in solving the aviation problem.

However, to be able to unlock the significant value inherent in SA mining, the country will have to solve a number of serious challenges. For the first time, SA was ranked among the world’s 10 least-attractive mining destinations in the 2021 Fraser Institute’s annual survey of mining companies. One major problem is the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy’s (DMRE) failed cadastre system SAMRAD, which led to a backlog of more than 4 000 mining and prospecting rights applications.

‘The Minerals Council has repeatedly suggested to the department that there are tested off-the-shelf cadastral systems developed in South Africa and used globally that could easily and relatively cheaply be purchased and deployed,’ says Seccombe.

‘Without a transparent, fully functional cadastral system, it is unlikely South Africa will reach its target of securing 5% of global exploration spend from its less than 1% currently.’ He adds that the DMRE recently updated Parliament on the progress, saying it had reduced the backlog by 40%. It also said it would also advertise a request for proposals on a new cadastral system by mid-December and finalise the process in Q1/2023.

Other major constraints that cost the fiscus billions in lost opportunities – according to Seccombe – include Eskom’s unreliable electricity supply (and more-than-sixfold price increase since 2008) and Transnet Freight Rail, which hampers the exports of bulk minerals (iron ore, coal, chrome, ferrochrome and manganese). The decline in rail capacity is owing to crime and cable theft (1 500 km copper cable stolen in five years), onerous government procurement rules, vandalism, idled locomotives bought in a corrupt transaction, poor maintenance and falling productivity at rail and at ports.

If these issues were solved, improved bulk export capacity at SA rails and ports could result in R151 billion of additional exports and 40 000 new jobs (bringing direct jobs in the sector to 500 000), while boosting taxes by about R27 billion.

The MCSA and its members have provided studies of bottlenecks and solutions, independent security assistance, partnerships on key corridors, engineering skills, and solutions for sourcing spares. ‘The answer to many of South Africa’s constraints on the economy, which are nearly all because of the dysfunction of state-owned entities, is greater private-sector participation in key infrastructure like electricity, rail and harbour logistics, water supply and roads,’ says Seccombe.

There is also the issue of illegal mining and other criminal activity. The industry is calling for a dedicated mining police task force with multidisciplinary teams to tackle ‘Mafia-type groups in procurement and construction’.

Faced with these problems and the tremendous potential of the mining sector at the same time, Fakude asked whether the country’s policymakers, and indeed the mining industry, would be able to organise themselves enough and in time to really benefit from the chance to lead the global transition to net zero carbon. She urged the sector to focus on hope instead of despair. ‘We must choose to see mining, despite its complex legacy and history, as an industry that is changing – and has changed – and that is an enabler of a more prosperous, sustainable and equitable future.’