From the time a local carbon tax was first mooted in 2010, mining companies were strongly opposed to it – not in principle, but for cost reasons. In regulatory filings, large mining companies acknowledge that cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is a necessity to address global warming. The mining sector contributes approximately 6% of SA’s industrial emissions.

Although they object to the additional tax, the country’s major mining corporations have proactively managed their energy/water consumption and carbon emissions for close to a decade in any case, driven by cost pressures and shareholder activism.

SA’s Carbon Tax Act came into effect on 1 June 2019, and follows the country’s 2016 commitment, through the Paris Agreement, to cut its GHG emissions. ‘The Carbon Tax Act gives effect to the polluter-pays principle for large emitters and helps to ensure that firms and consumers take the negative adverse costs (externalities) into account in their future production, consumption and investment decisions,’ National Treasury states in an introduction to the act. ‘Firms are incentivised towards adopting cleaner technologies over the next decade and beyond.’

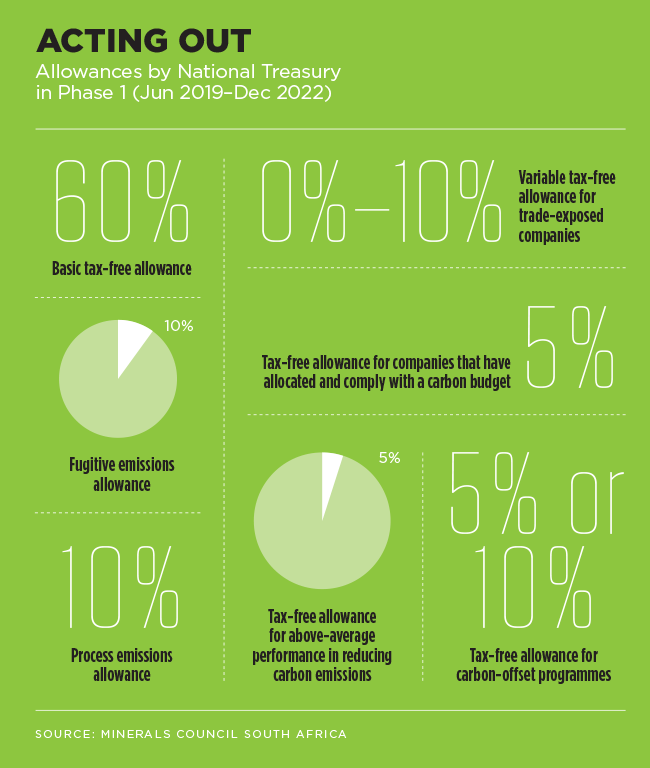

From June 2019, the first phase of the broader implementation of the carbon tax kicked off, with carbon tax imposed on petrol at a rate of 9c/litre and diesel at a rate of 10c/litre. In Phase 1 (from mid-2019 to end-2022), carbon tax is levied at a rate of R120/ton of GHG emissions above a threshold level on certain specified activities. There are various transitional tax-free allowances, ranging from 60% to 95%, and in this stage the tax will not raise the price of electricity. National Treasury says the offsets would result in an effective rate of R6 to R48/ton of CO2e emitted in the first phase.

The costs of the tax are likely to rise steeply in the second phase, and will cost the mining industry about R5.5 billion a year, according to Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) estimates, based on a survey of 18 companies. At this stage, however, there are various uncertainties about the Phase 2 costs.

National Treasury says the tax will be reviewed before the start of the second phase, and then there would be changes to tax-free thresholds and rates, depending on progress. These changes would be subject to transparent and consultative processes.

The Carbon Tax Act is part of a suite of associated laws and regulations in the pipeline, including the National Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reporting Regulations, carbon offsets and carbon budget, which will be described in the Climate Change Bill.

‘The mining industry is not only facing the impending pressure of increased input costs under the carbon tax regime, but also the difficulty of navigating a complex regulatory framework administered by different organs of state,’ says attorneys Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr in a commentary on the introduction of the carbon tax. And, according to Izak Swart, director of carbon tax and government at Deloitte, ‘very few emitters will not be affected by carbon tax in some way, and now is the time to make sure you have taken the necessary steps to prepare’.

The MCSA, in its objections to the Carbon Tax Bill, argued that while a carbon tax was one of several measures that could be used to cut GHG emissions, given the socio-economic implications of the tax, already-falling emissions and challenges in implementing the bill, it did not support it. Any increase in the costs of mining would undermine its ability to create jobs, it said, adding that there should instead be a ‘toolbox’ of incentives and disincentives to mitigate climate change.

Over the past few years, some of the industry’s initial arguments against the tax have weakened. The prices of many commodities have improved, Eskom has started to diversify its power sources away from coal and its customers have been given limited permission to generate their own energy from renewable sources. At the same time, European-based funders have become increasingly insistent that global mining companies should report in detail on their policies to tackle climate change, and many large institutions are refusing to finance new coal-fired projects. SA’s mining companies are heavily dependent on external financing.

Global companies are now expected to report their Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, according to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Standard. Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions, for example, from boilers, vehicles and air-conditioner leaks. Scope 2 emissions are indirect, from purchased electricity, heat, steam and the like, while Scope 3 covers all other indirect emissions from sources the organisation does not control, such as business travel, procurement, waste and water.

Mining companies are responding to concerns about climate change and mitigating the costs of carbon taxes through more detailed analysis of and reporting on their emissions, undertaking portfolio reviews, and taking steps to cut coal-fired electricity consumption and/or generate their own power from renewable sources.

Both Anglo American and Glencore have hinted that they do not intend to expand their thermal coal portfolios, and Anglo American has gone even further by selling all its thermal coal mines. Glencore has said it will review whether its membership of certain trade associations aligns with its commitment to the Paris Agreement. Glencore announced, in 2017, its first target to reduce GHG intensity by 5% by 2020 (compared with its 2016 baseline) and says it is on track to meet the target. It is developing new, longer-term goals, which it will report on from this year. It will also start to disclose its mitigation efforts on Scope 3 emissions and report on how its investments in exploration and development of fossil fuels are aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Meanwhile Anglo American has – for several years – been working on its FutureSmart Mining project,– which applies the latest technology to transform mining methods . FutureSmart mining methods radically reduce Anglo’s energy consumption, moving it towards carbon neutrality. Anglo has set itself the goal of improving energy efficiency and reducing absolute GHG emissions by 30% by 2030, a goal linked to executive incentives.

In 2018, the group saved more than 6 million gigajoules of energy consumption through implementing 440 energy-efficiency and business-improvement projects. These included trials of shock break technology; expanding coal methane capture (which is used in power stations) at the Moranbah North and Capcoal underground mines in Australia; and introducing emission-related criteria in its sourcing policies. In SA, Anglo’s subsidiary Kumba Iron Ore, which operates the decades-old opencast Sishen iron ore mine, has achieved significant energy savings through, for example, improving its payload management systems, implementing a diesel energy-efficiency management programme and optimising the loading of haul trucks.

For several years, Harmony Gold Mining has been disclosing its carbon-related impact, and its 2019 annual report lists its Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions for the past five years. The miner states that electricity contributed about 15.8% of operating costs in its SA operations, so its energy and climate change policy was driven by economic and ecological imperatives. Its focus was on being more energy-efficient and reducing carbon intensity, as well as diversifying its energy mix. It’s closed several carbon-intensive operations and plans to replace 30% of its carbon-based electricity consumed in SA with renewable energy within the next three years. It has also been given environmental authorisation for three 10 MW PV power plants and is concluding procurement processes, while looking at bio-energy and ways to reduce power consumption.

Impala Platinum Holdings (Implats) has been working on cutting its electricity consumption for several years and in its latest annual report says it had already realised as much energy saving as it could without investing significant additional capital. It says it intended to continue optimising its energy use to reduce its carbon tax liability. This year, Implats is aiming to reduce Scope 1 emissions by 2% on 2017 levels (to 392 kilotons), and Scope 2 emissions by 5% on 2008 levels (to 2 568 kilotons). It is working on developing more accurate and auditable data on Scope 3 emissions from all operations.

One of the challenges facing Implats in reducing Scope 2 emissions is that its new, deeper shafts will require more energy for transport, refrigeration and ventilation.

Some of Implats’ energy efficiency projects include more energy efficient lighting underground, optimised use of underground compressed air systems, installing power factor correction equipment at Impala Rustenburg and Mimosa, and diesel performance management. In the longer term its use of fuel cells will help reduce its peak energy demand and make underground equipment usage more environmentally friendly.

Implats states that it has been calculating its group GHG inventory since 2008 on a voluntary basis and reporting its GHG emissions every year. Its Scope 1 and 2 emissions are audited. This year, it will review its reporting approach in line with the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures.

While larger mining companies in SA are tackling climate change concerns seriously, the smaller companies still have some way to go. However, the necessary attention to detail, as well as the costs, entailed in the new carbon tax are likely to improve their responsiveness.