In March 2023, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, one of two national banking regulators in the US, announced it was setting up an Office of Financial Technology. To lead it, the OCC appointed Prashant Bhardwaj, who had an impressive 30 years of experience in the financial sector.

Bhardwaj lasted less than four months. While the OCC would not confirm the reasons for his departure, it emerged in media reports that Bhardwaj might have been less than truthful on his CV – claiming, for example, that he had worked for Citibank during a certain period. However, as Fintech Business Weekly pointed out, he would have been just 13 at the time. It was not the only entry on his CV to raise eyebrows. For example, he obtained his MBA from an unaccredited institution – a diploma mill – in Belgium.

Of course Bhardwaj is not the first person – or the last – to fudge his qualifications. SA has recorded a number cases where people in senior positions have bent the truth about their qualifications.

‘The falsification of credentials has become an increasing concern in the South African job market,’ says Sifiso Cele, founder and MD of recruitment firm Ndosi KaMagaye Search Partners. ‘We’ve seen a number of high-profile cases where candidates have misrepresented their qualifications, work history or other credentials in an effort to secure employment. This is a troubling trend that undermines the integrity of the hiring process and can have significant consequences for our clients.’

Two UCT associate professors Linda Ronnie and Suki Goodman write in a recent Conversation article that falsifying academic transcripts ‘is made easier by the availability of sophisticated technology’.

According to a recent US survey, almost three-quarters of the respondents said they would consider using AI tools to help embellish or lie on their resume. While that may be true, Arthur Goldstuck, founder of World Wide Worx, points out that fake qualifications have always been a problem, even before the advent of the AI and ‘deep fake’ technology. There is nothing wrong with job hunters using generative AI such as ChatGPT to fine-tune their CVs. After all, as Goldstuck points out, that is one of ChatGPT’s purposes. However, in a competitive jobs market, the temptation to further embellish one’s credentials is a problem.

Canadian researchers Sarah Eaton and Jamie Carmichael, whose book Fake Degrees and Fraudulent Credentials in Higher Education was published last year, estimate that the global fake degree industry is worth $21 billion a year. ‘That’s the dollar figure amount that most people in higher ed are unaware of,’ says Eaton. She points out that there are different kinds of degree fraud. ‘There are degrees from fake universities, ones that are just a URL. Some companies sell forgeries, where you select the university and degree you want, and they’ll create it for you. And it could be a real university that they create this degree from.’

Andrew Fennell, CEO of StandOut CV, which offers an online CV-building service, writes in a recent post that Google searches on how to lie on your CV rose by 19% from 2022 to 2023. In the company’s 2023 survey of more than 2 100 Americans, almost two-thirds (64.2%) admitted to lying on their CVs at least once. About 30% lied about their college degree on their CVs, with about half of those saying they had a degree when they didn’t.

Fennell says fake degree certificates and transcripts can be bought online for an average of $197.83.

In its own investigation, local online publication MyBroadband discovered, after just a cursory search, at least 10 websites offering fake degrees at various prices ranging from $189 to $800. One site, contactable through a WhatsApp number in China, offered a degree from the London School of Economics for only $650, including delivery of the physical piece of paper, presumably for you to frame and hang on your office wall.

But a warning… You could face up to five years’ jail time and/or a fine if you are caught lying about your credentials.

The National Qualifications Framework Amendments Act of 2019, which came into effect in October 2023, provides that ‘a person is guilty of an offence, if such person falsely or fraudulently claims to be holding a qualification or part-qualification registered on the NQF or awarded by an education institution, skills development provider, QC or obtained from a lawfully recognised foreign institution’.

Jon Foster-Pedley, dean and director of Henley Business School Africa, has welcomed the legislation, but argues that institutions need to step up to do their part to address the problem. ‘One person lying about a degree can have an outsize effect, potentially undermining the performance and credibility of the business they work for or, if they are in the public sector, compromising service delivery to thousands, he says.

‘It’s not hard to see how, over time, each drip of dishonesty adds up to a flood that could erode the foundations of the entire education sector and ultimately the economy.’

Goldstuck says the advent of AI has made it easier to verify qualifications. ‘In the same way that AI can be used to create more convincing fakes, it can be used to catch out those fakes. [ChatGPT-4] allows you to upload documents, images, certificates, PDFs and analyse them and identify issues. And it’ll keep on getting better at it.’ He predicts the emergence of AI platforms dedicated to catching out fakes that will be integrated with university databases. ‘It’s still all in its infancy, bearing in mind that ChatGPT is only 18 months old in terms of public access,’ says Goldstuck.

‘AI-based tools have the potential to enhance the speed, accuracy and comprehensiveness of our credential checks, which could be particularly valuable, given the increasing prevalence of credential falsification,’ says Cele. Ndosi KaMagaye Search Partners utilises a multi-faceted approach to credential verification that includes making use of various online databases and verification services.

‘We are also actively experimenting with the integration of AI technology to enhance our verification processes. These include AI-powered automated document verification that can be integrated into our various workflows for qualifications verification.’ Cele adds that the firm is testing how ‘AI-powered chatbots can be integrated into HR and recruitment workflows to provide instant support to employees performing verification workflows’.

Henley Business School Africa, meanwhile, has introduced a real-time digital and encrypted certification system for its qualifications. The system, introduced by Privy Seal, allows a prospective employer to click on a unique link or use a supplied QR code to determine a qualification’s legitimacy.

‘The ability to confirm a certificate as genuine in real-time is important to building trust,’ says Stephen Logan, founder and director of PrivySeal. ‘It enables third parties to have faith that they are dealing with a recognised, responsible person who holds a proven and top-class qualification. In the era of AI where “deep fakes” are becoming easier than ever and videos and even likenesses can be easily forged, this kind of system is no longer a nice to have but a must have for organisations to be able to prove their identity and the authenticity of their qualifications,’ he says.

UCT’s Ronnie and Goodman point out that corporates and universities already have access to an online degree authentication service. Called Managed Integrity Evaluation (MIE), it links universities or colleges to a database, which third parties can access to verify Grade 12 certificates and a range of tertiary qualifications, including degree, diplomas and short courses, both local and international. In addition you can check whether the academic institution is accredited by the relevant governing body. It also offers financial regulatory verifications to ensure a job candidate in the finance sector is compliant with the relevant legislation.

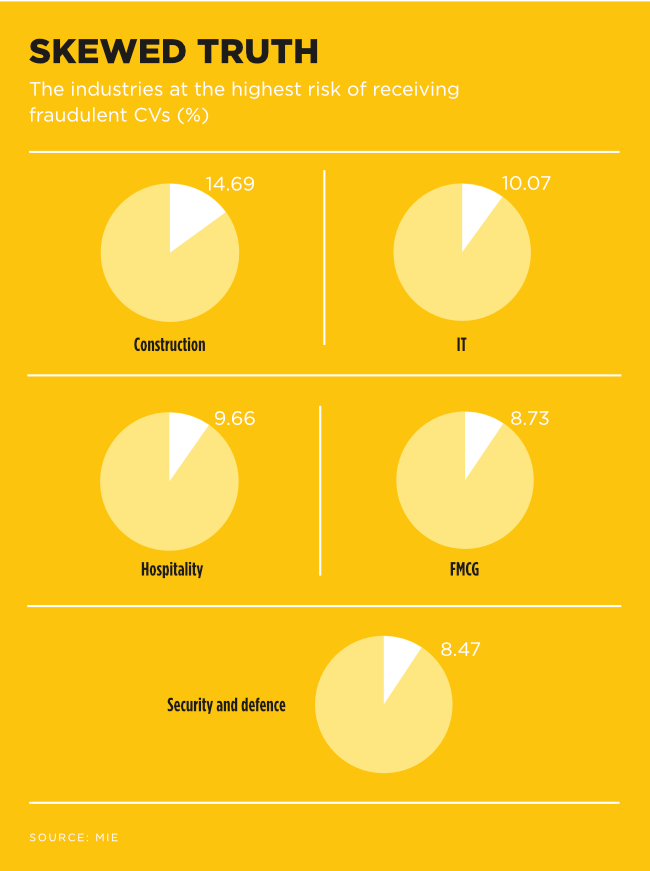

MIE, based in Centurion, also publishes an annual background screening index, noting the risks encountered while screening job candidates. In its latest index, it reports that, for first time since 2012, it recorded a rise in overall risk associated with qualification verification, from 5.99% to 6.86%.

The qualifications that carried the highest risk were skills programmes (25.29%) and FSCA-approved qualifications (12.14%), while the construction and IT industries carried the most amount of risk.

MIE also notes that the volume of requests for qualification verification is increasing, by almost 10% year-on-year, ‘indicating increased awareness around the importance of conducting qualification verification as part of the screening process’. And that is an important point. Verification tools might be the latest in available high-tech, but what good are they if they are not actually used?