The great unwritten rule of family businesses is that the wheels come off with the third generation. The theory is that after the first two generations, the third feels that success is a birthright and falls into complacency. That’s the rule. But is it the reality?

Rob Slee, author of Time Really Is Money, points to a US study from the 1980s, where the Family Firm Institute (FFI) found that about 30% of family-owned businesses survived into the second generation; about 12% were still going in the third; but barely 3% made it to the fourth generation and beyond. ‘I checked a couple of dozen websites of business succession advisers, and each quoted the FFI statistics as if they applied today,’ Slee writes in a recent online post. ‘I don’t think they do. In fact, at least for the middle market, I’d be shocked if more than 10% of family businesses are now transferring to the second generation.’

Slee then looked at hundreds of family businesses, finding that in at least 90% of the companies, neither generation wanted any part of a transfer.

Staying in North America, the Family Business Report 2023 found that 61% of US family businesses do not have a formal succession plan in place, even though nearly half list ‘managing succession’ as a core mid-term objective.

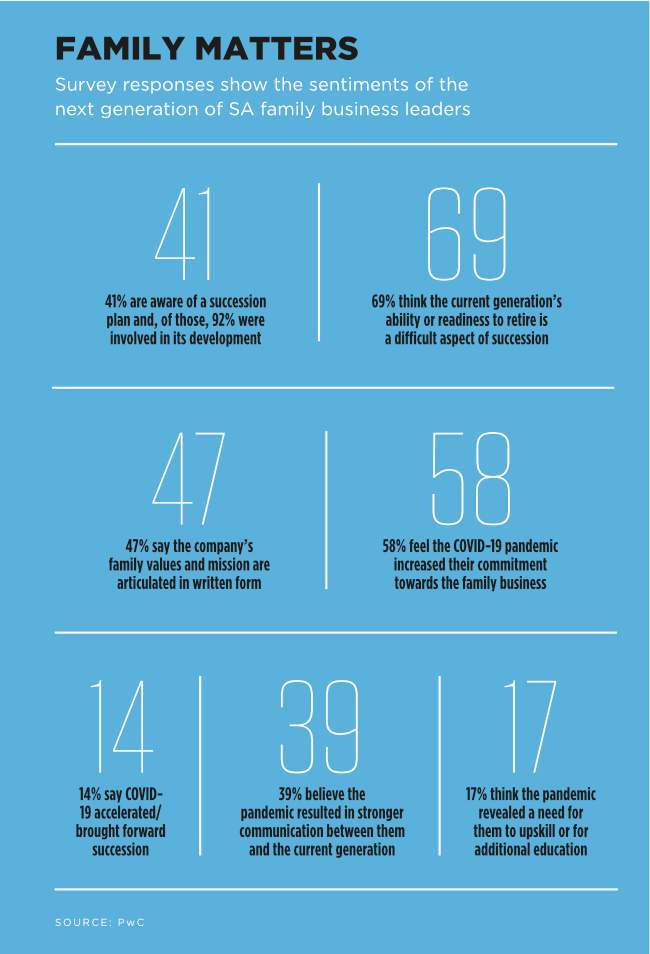

Closer to home, PwC’s Africa NextGen Survey 2022 found that 50% of the next generation believed their family business had a succession plan – significantly up from the 24% who said so in PwC’s 2021 Africa Family Business survey. PwC’s focus on the next generation is useful because, as it quotes Kenneth Goh, academic director at Singapore Management University’s Business Families Institute, as saying, ‘the responsibility for generational transition does not fall solely on the shoulders of the current generation. NextGen can play an active role by “managing up”, based on mutual respect and good communication across generations, to set the pathways for senior leaders that affirm their identity and status’.

In business, family problems start early. Catherine Wijnberg sees this every day in her work as founder and director of SA SME and start-up incubator Fetola. ‘As we work with early-stage businesses the problem we often face is undefined family relationships, lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities, and early-stage entrepreneurs trying to back out of promises they made to relatives in the naïve stages of starting a business,’ she says.

‘Our focus is to help entrepreneurs formalise and rationalise partnership agreements and align remuneration expectations from family members according to their contribution to the success of the business, rather than as a result of the family connection.’

How, then, should first-generation entrepreneurs look to adequately and appropriately groom their heirs to take over from them, setting they up for success? ‘This is seldom a simple matter,’ says Wijnberg. ‘Here I will speak to my own experience with a father who built up a large national construction company. None of the five educated children showed any desire to take over the business, so he was unable to pass ownership to them or introduce suitable succession or exit plans. Once he retired, the once-thriving business was closed with the loss of thousands of jobs. Only an estimated 7% of founders do manage to pass on the business to the next generation – and the numbers tell the story of how difficult this is in practice.’

Part of the challenge also lies in business owners simply not wanting to let go. In his online post, Slee shares the example of an 85-year-old entrepreneur who sought his firm’s help to effect an inter-generational business transfer. ‘The man was distraught because “Junior” had recently been offered the chance to buy the family business but had declined the opportunity,’ writes Slee.

‘The elderly owner castigated the younger generation for their flimsy work ethic and lack of vision. I later discovered that Junior was 62 years old… Junior told me he had worked in the business for more than 30 years and had offered to buy the business more than 10 years before, but the “old man” wouldn’t even discuss it.’

PwC’s Africa NextGen Survey 2022 found that 64% of the SA next-generation business owners are already in a leadership role, with 36% wanting to play an intrapreneurial role in the next five years, and 22% wanting to play an entrepreneurial role. However, the report notes that only 28% of those NextGens have been given the opportunity to lead a specific change project or initiative within the family business.

The answer may well lie in bringing in outside help. In a recent opinion piece for MoneyWeb, Tiaan Herbst of the Southern African Advisory Company cited the Rupert family’s Reinet Investments as an excellent example of how to run a family business professionally and responsibly.

‘Their board of directors includes both family and non-family members, ensuring that the company is run with an objective and unbiased approach,’ writes Herbst. ‘Small-business owners can learn from Reinet Investments’ example by adopting effective governance practices and establishing clear policies and procedures. By creating a culture of professionalism and responsibility, businesses can avoid bad judgement, weak leadership and a refusal to take responsibility.’

That culture of professionalism can also help reduce the frictions and squabbles that so often come from running a business alongside one’s parents, siblings and children. After all, as PwC’s 2023 Family Business survey found, ‘conflict within the family has a spillover effect on building trust across the wider business. More than one in five respondents say family disagreements are the biggest challenge when building trust with all stakeholders’.

The report concedes that ‘dealing with conflict has never been easy for family businesses. It’s part of an ongoing struggle many have with establishing strong family governance structures’. Indeed, in the 2021 edition of the survey, only 15% of respondents said they had conflict resolution mechanisms to deal with family disputes. The 2023 survey saw that share increase (marginally) to 19%. ‘Only 65% of family business leaders say they have formal governance structures in place,’ the report adds. ‘This includes shareholder agreements, family constitutions and protocols, and even wills.’

All too often, family feuds get in the way of family business. Or, as Robert Slee puts it, ‘with all the dysfunction that exists in families, it’s amazing to me that family businesses can even stay in business, let alone plan for a transfer. My advice to the industry – first bring in the psychologists’.

Herbst agrees, writing that ‘the ability of a family business to make decisions and get work done without being hampered by interpersonal conflicts is directly correlated to the openness and transparency of its culture’.

To that end, families can hold regular council meetings for those within the family trust to promote open communication. ‘Conflicts between employees can be reduced in small businesses by encouraging open dialogue and personal accountability,’ writes Herbst.

That level of open discussion can also mitigate the negative effects of members of the next generation jostling for power. While that makes for good television (as in the Emmy-winning show Succession), it seldom makes for good business.

‘Succession planning is not something that happens overnight,’ says Wijnberg. ‘Small businesses often revolve around the skills and passions of the founder, and these are seldom found in others – let alone their own children.

‘If the business grows to the scale of Pick n Pay, for example, there are multiple roles for family members to suit their individual skills, but in a small business to replicate the mother – or father – with the same passion, purpose and potential is tricky. As the numbers show, it’s only possible in seven out of every 100 businesses.’

Wijnberg’s recommendation? Like Herbst, she suggests combining the family’s vested interest and innate insights with an outsider’s arms-length professionalism.

‘My own strategy is to build a cross-cutting team of capable staff to ensure professional management that is not swayed by family emotions, and to enable their shareholding in the running of the business,’ she says. ‘In this way it’s possible to transition leadership to the most qualified individuals, and retain some value for the family through shareholding rather than management.’

That approach helps to ensure continuity for the business, and wealth – rather than jobs – for the family.