One thing that all of SA’s corporates failures in recent years have in common is ‘a dominant CEO who did not bode dissent or challenge’. This is according to Ansie Ramalho, chairperson of the King Committee on Corporate Governance. ‘One wonders how it was that the chairs did not pick up on this and dealt with it as it exposed these companies – including African Bank, Steinhoff and Tongaat – to the risk of operating without proper challenge and interrogation. The board – and the chairperson taking the lead on this – sets the tone for the culture at the company; it should not be passively left to the CEO to dictate without checks,’ she says.

‘In fact, it’s this very notion that is fuelling the perpetual governance concern about how it can be ensured that managers look after the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders with the same vigilance as they would look after their own. How to deal with this dilemma has become the main quest of corporate governance. The practice of having a strong, independent chair in place so as to balance the power of the CEO is one of the typical solutions proposed by governance codes.’

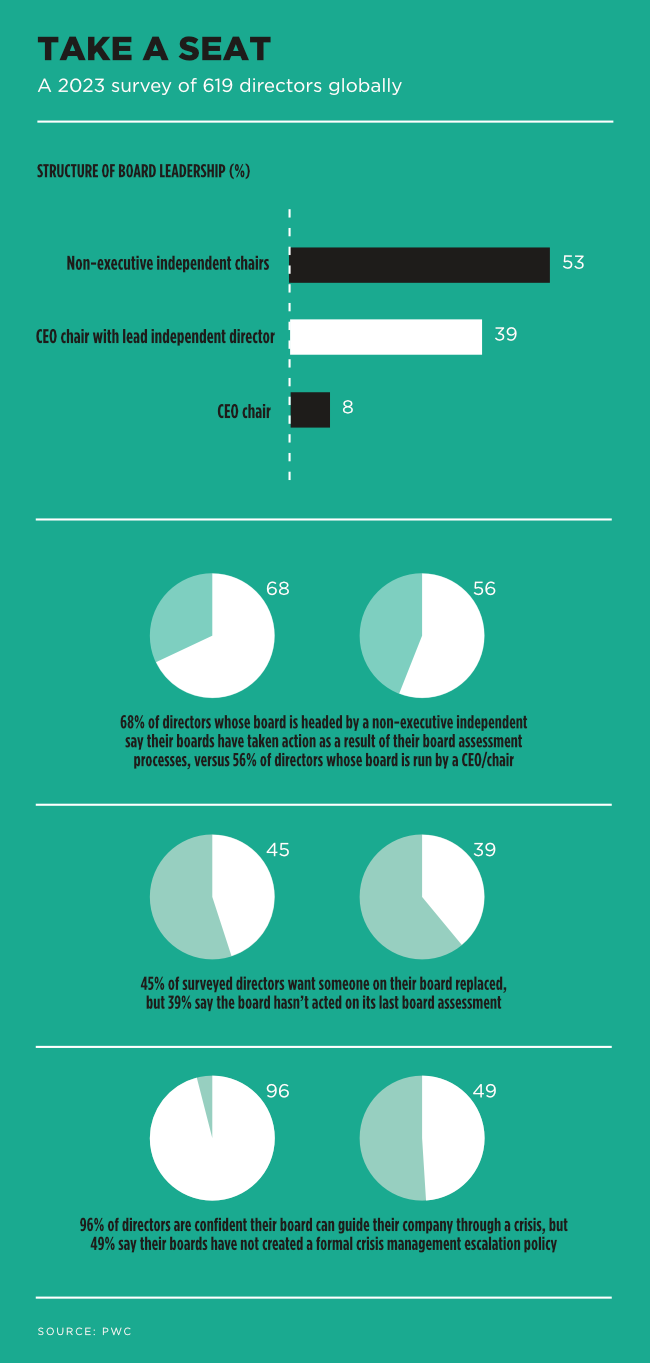

Across the globe, the chair of the board of directors has evolved from historically holding a procedural and ceremonial position to a much more complex and demanding role in companies, according to Rehana Cassim, professor in company law at the University of South Africa. ‘Today the chair is seen as vital for effective corporate governance. They are required to lead the board in filling its governance duties and responsibilities.’ To illustrate this point, she refers to a US survey on global board culture that found the effectiveness of the chairperson to be ‘the single-biggest differentiator between the most and least effective boards’.

Along with the changing tasks and skills required to chair the board, the job title has also been updated. In 2019, 98 of the companies listed in the FTSE 100 still used the title ‘chairman’ even when the head of their board was a woman, writes the Times. However, by April 2024 more than half (62) of the FTSE 100 companies had quietly swapped their term ‘chairman’ for ‘chair’ in their move towards gender-neutral language.

‘Terminology, while important, is secondary to the effectiveness of the role itself,’ says Parmi Natesan, CEO of the Institute of Directors SA (IoDSA). ‘Whether you call it “chair”, “chairperson” or “chairman”, the key is that the person in the role is able to lead the board effectively and uphold good governance practices. The King IV Code uses the term “chair” for simplicity and inclusivity, but that doesn’t imply that other terms are incorrect.’

Globally, evolving governance codes such as the King Code have raised the importance of the chair’s role at the apex of the company, turning it into one of the most challenging roles in the corporate world, and – according to the IoDSA – also ‘possibly the least understood’ role. ‘The primary role of the chair is to provide leadership to the governing body of an organisation and set the tone for the oversight of its performance,’ says Natesan.

It should be a power balance between the chair and CEO in which their roles are distinct but complementary. ‘The chair leads the board, ensures effective governance and considers the interests of stakeholders. The CEO, on the other hand, is responsible for the day-to-day management of the company and executing the board’s strategy. In well-governed companies, neither the chair nor the CEO holds absolute power; their influence is balanced by the board’s collective decision-making process, which is designed to ensure accountability and effective oversight.’

Simplified, the CEO and chairperson fulfil similar roles at two different levels. As Cassim puts it, ‘the chairperson is expected to manage the board’s business, while the CEO is expected to manage the company’s business’.

Ramalho explains the difference like this – the CEO is hands-on (hence the word ‘management’, which is derived from ‘manus’ in Latin meaning hands) and responsible for operations. The chairperson leads the governance effort, which is the task of the board as a whole, and which can be summarised as giving direction and exercising oversight. She adds that as is the case with governance at national level, it’s important that there’s separation of powers so that checks and balances remain intact.

That’s why the King IV Report recommends that one person should not hold both the positions of CEO and chairperson. In practice though, these roles are sometimes combined, says Cassim. She gives the example of Eskom Holdings appointing Jabu Mabuza as the chairperson of the company in January 2018, and in July 2019 also as the acting group CEO. The National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa strongly objected, because it would mean that Mabuza would be reporting to, and would be accountable to, himself. Despite the union’s objections, he served in both positions until January 2020, when André de Ruyter became the new group CEO, says Cassim.

While in smaller companies the two roles are sometimes combined, she explains that this overlap is not recommended for larger private companies and public companies, which ‘must guard against concentrating power in the hands of a single individual’.

There are, however, no binding regulations – only recommendations – to ensure the roles of chair and CEO are held by separate individuals. Like King VI, the JSE Listings Requirements also encourage the separation of these roles, particularly in listed companies, says Natesan. When it comes to a majority shareholder being appointed as chair, there are again no explicit prohibitions, she says, but King IV advises that the chair should be an independent non-executive director. ‘This recommendation is designed to ensure that the board remains independent and that decisions are made in the best interest of the company as a whole, rather than being unduly influenced by a single stakeholder,’ she adds.

But can the presence of an independent chairperson ever be an effective check?

‘Certainly not on its own, seeing as the CEO is at the company full time and the non-executive chair has only sporadic interaction with the company, mostly through board and board committee meetings – the consequence of which is significant asymmetry of information,’ says Ramalho. She argues that having an independent chair should be seen as only one of the practices within the broader holistic governance arrangements that protect the company and its stakeholders against ‘opportunistic behaviour by management or, more mundanely, simple human error’. The other checks include having a competent, vigilant board and board committees, and strong internal controls and assurance.

‘How effective the governance effort is depends on whether the directors are competent and ethical,’ says Ramalho. ‘A poor chairperson acts like a lid on the potential of the company; a good one lifts its potential.’

To be effective, directors and especially a chairperson need to spend time reflecting on the affairs of the company, outside of meeting responsibilities, she adds.

‘This would include staying abreast of developments and emerging issues in the industry, reading between the lines of reports submitted to the board, and contemplating the actions of the CEO and the dynamics within the management team. The idea with this reflective stance is to spot issues as soon as they arise and get ahead of potential risks.’

Since the chairperson has the most important role in delivering effective corporate governance in contemporary companies, Cassim would like to see the Companies Act, JSE Listings Requirements and King IV provide more guidance on the chair’s functions and powers, and what is expected of them. Another suggestion is for King IV to cap the number of years the chair may serve. Ideally at nine years, she says, to give the chairperson ‘enough time to develop a relationship with the board and still enable them to retain their independence’.

As SA’s legal instruments don’t require the chairperson to have any professional qualifications, Cassim suggests that companies should include minimum qualifications in their memorandums of incorporation that a director must meet before becoming eligible for appointment as the chairperson.

To address the unique challenges faced by aspiring chairs, the IoDSA has designed a knowledge-sharing programme with practical case studies and discussion.

The Masterclass for Board Leadership covers governance best practices, leadership, strategy and board effectiveness, among others. And while ‘chair of the board (SA)’ won’t become its own professional designation at this stage, future board leaders will benefit from efforts to strengthen the relatively new director designations of certified director and chartered director (SA).

By ensuring that these designations align to the director competency framework, the IoDSA’s programmes go a long way towards instilling those leadership aspects that can’t be legislated, such as effectiveness, competence and ethics – which are the building blocks for developing chairs and CEOs who understand their roles and the power balance required to lead thriving companies.