If you were blindfolded and dropped off in Lusaka, Zambia, you might mistakenly imagine yourself in a suburb of Johannesburg or Cape Town,’ says Grieve Chelwa, senior lecturer in economics at UCT’s Graduate School of Business (GSB). ‘South Africa’s economic influence is felt so strongly in Zambia that it’s changing the local character – and I suspect it’s similar in other countries within SADC.

‘Go to any supermarket in Zambia and you’ll be greeted by shelves full of South African brands. The shopping malls are populated by South African companies, and everywhere are branches of big South African banks.’ The Trade Law Centre (Tralac) names Zambia as one of the main destination markets for SA’s intra-African exports, with the others being direct neighbours Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

Until recently, SA chains Shoprite, Pick n Pay, Spar, Woolworths and Food Lover’s Market have dominated the internationalisation of supermarkets in the continent, although over the past decade other African chains (such as Botswana-owned Choppies Enterprises) have spread in Southern Africa, says Reena Das Nair, senior researcher at the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development, University of Johannesburg. ‘Supermarkets can transfer their own culture to host countries to varying degrees. ‘The cultural hurdle may be more easily overcome in markets closer to home, in addition to supply chains being shorter,’ she writes in an article for Development Southern Africa. ‘In Zambia, Shoprite had the first-mover advantage when it bought former state-owned supermarkets during the privatisation phase in the 1990s. Essentially “taking over” the local competition, Shoprite grew initially via acquisitions and then organically.’

By far the biggest SADC economy, SA has benefited from the enabling business environment and particularly the free-trade agreement between 13 of the 16 SADC member states, which only the Comoros, DRC and Angola haven’t yet joined. According to Tralac, SA – as a member of the five-nation Southern African Customs Union (SACU) – is further benefiting from duty-free intra-SACU trade and a common external tariff that is applicable to all goods entering from outside the union. (It also includes Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho and eSwatini.)

The latest private-sector investments in the region were announced in August 2018, when SA handed the SADC chair to Namibia during the regional body’s annual Summit of Heads of State and Government, held in Windhoek. ‘Over the period of our chairship, we have been able to secure more than $500 million of committed productive investments by South African companies in each of the priority value chains across the region,’ President Cyril Ramaphosa said in his keynote address at the summit. Summing up the nation’s 12-month tenure, he noted that the ‘investments cover forestry, agriculture and agro-processing, fertilisers, mining and mineral processing, and pharmaceuticals’.

The creation of regional value chains (RVCs) that link priority sectors across various countries in the region – coupled with industrialisation efforts – is crucial because it’s likely to boost smaller economies and local labour. SADC has already rolled out its Industrialisation Strategy and Roadmap 2015–2063, which prioritises mining, agro-processing and pharmaceuticals as critical sectors in eight nations (Angola, Botswana, eSwatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Namibia, SA and Zimbabwe), with more to follow. The SADC secretariat is currently profiling the agro-processing sector, looking into high-potential products, modes and costs of transport for goods and services, product markets, prices, production and trade modalities. The body’s official newsletter states: ‘Between April 2018 and March 2019, the SADC secretariat – together with member states – is targeting to start the implementation of regional value chain projects, covering leather and associated products; soya; aquaculture; iron and steel; copper, fertiliser and anti-retroviral drugs.’

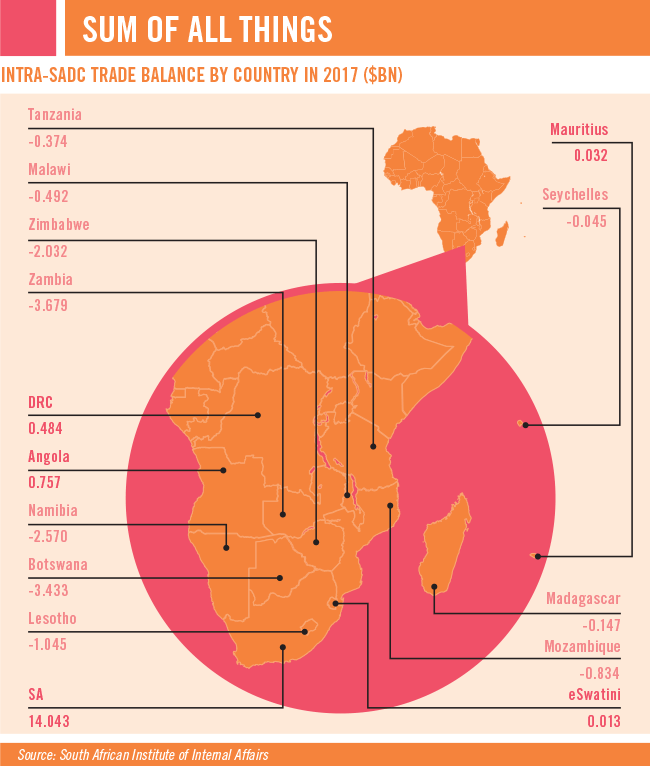

Stronger RVCs will assist in narrowing the trade and investment disparities that are still heavily skewed in favour of SA. According to a recent report on SADC’s regional economic development by the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), SA had a $14 billion trade surplus in 2017 – far greater than any other SADC state. Angola recorded the next largest surplus ($0.76 billion), followed by the DRC ($0.48 billion), Mauritius ($0.03 billion) and eSwatini ($0.01 billion).

The publication doesn’t yet incorporate the Comoros – the French-speaking archipelago between northern Mozambique and Madagascar, which is part of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and only joined SADC at the 2018 Windhoek Summit. ‘Among SADC’s 15 [now 16] countries, five recorded a trade surplus with their SADC counterparts in 2017, of which 10 were net importers,’ states SAIIA. ‘These figures illustrate that trade within the regional economic community is remarkably skewed, rendering smaller economies dependent on South Africa for imports of higher-value goods and services.’ The authors explain that this has been called the ‘triangular pattern’ of SA trade – where the country runs a trade surplus with SADC and a trade deficit with the rest of the world, which effectively turns it into the gateway for global products entering the SADC market.

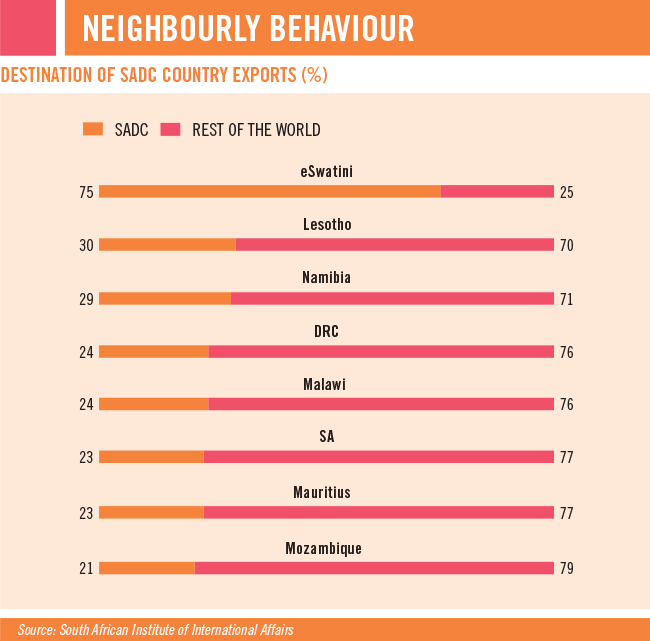

There are also ‘stark’ differences in export volume among SADC members, according to the SAIIA research. SA accounted for almost 67% of total intra-regional exports in 2017, compared to a mere 6% for the next largest exporter, DRC. ‘This disparity highlights how South Africa’s economy sets itself apart from the rest of the region by attracting large industries with its sizeable market. Owing to its larger economic base, it has been able to benefit from economies of scale to enable exports, in contrast to smaller economies in SADC,’ states the report.

In its current set-up, SADC is ‘a wonderful thing’ for SA but not so great for other members, says Chelwa. ‘It’s comparable to a very minor soccer team competing against Brazil in the Fifa World Cup, because it’s equally one-sided.’ The intra-SADC relationship benefits SA companies more than other players in the regional bloc because the value gravitates towards SA, as companies use their home-based supply chains and repatriate their profits, he says. ‘Companies must be incentivised to build capacity in other member states. Yes, South African companies create some employment but this is primarily in the services sector rather than the large quantity of industrial and manufacturing jobs that SADC requires.’

Statistics on this topic can be found in the Labour Research Service (LRS) database, which, since 2008, has tracked 91 SA multinational corporations (MNCs) operating across the continent – providing information on companies’ finances, operations, geographical spread and remuneration policies. Zambia, eSwatini, Namibia, Mozambique, Lesotho and Botswana are the countries hosting the highest number of sampled companies. According to LRS’ MNC Trend Report, the following SA companies achieved high returns in Africa during 2016: Pretoria Portland Cement (PPC) reported African sales at 30% above the calculated average, followed by Group Five (28%), Barclays Africa Group (24%), Tsogo Sun (20%) and Shoprite (19%).

In December 2018, Shoprite opened its 35th supermarket in the Novare Great North Mall in Lusaka. ‘This is our 11th store in the capital city, having entered the Zambian market 23 years ago,’ says Charles Bota, GM of Shoprite Zambia. ‘This opening provides 142 people with jobs and adds to our 4 200-strong workforce. Well over 50% of our employees are women with more than a quarter youths [being] under the age of 24.’

Around 78% of produce stocked in this supermarket is locally sourced, in line with attempts to use more local suppliers. However, if this applies only to agricultural produce and not to the retailer’s other goods and services, it will not be enough to stimulate regional value chains, which are paramount for long-term sustainability.

However, SADC is already making progress in its harmonisation efforts. For example, its regional electronic settlement system is building a platform for increased intra-SADC trade and investment. The roam-like-at-home initiative is developing a harmonised cost model for cellular roaming tariffs, while the objective of the Medicines Regulatory Harmonisation project is to strengthen public health networks and eventually also pharmaceutical RVCs.

Ultimately SA, as the largest player, is not wielding all the power in the regional bloc, as other members exert ‘soft power’ through their diplomatic or cultural influence, according to the Institute for Security Studies. The use of regional ‘champions’ or ‘locomotives’ could drive certain cross-cutting issues ahead. For example, the institute considers Namibia a champion of gender mainstreaming, and refers to Mauritius as a champion of ‘productive competitiveness’.

Once member states are allowed to combine their cultural, political and economic strengths, the entire regional economic community is set to benefit.