Lately there seems to always be some type of investment story for Africa along the lines of ‘Lions on the move’ or ‘Africa rising’ doing the rounds. In terms of private equity (PE) investment, Heleen Goussard, head of unlisted investment services at RisCura, says that African tale of late is a growth-driven one. ‘Many regions in the rest of Africa outside of SA have shown economic growth of more than 6%,’ she says. ‘It’s compelling for any investor.’

According to the latest Africa Private Equity & Venture Capital Index, which comprises 51 funds focused on PE and venture capital investments in Africa, these funds had a total capitalisation of more than $12 billion as of end-March 2018. The index includes pan-African, regional and country-specific funds, 13 of which are focused primarily on SA. Before looking at the various regions and traditional investment sectors within them, one needs to digress and explore a few relatively new opportunities on offer.

The narrative of Africa as a burgeoning investment frontier may appear simple, yet within is a more complex thread – one of opportunity created by technology. ‘It enables Africa, and businesses on the continent, to leverage without the infrastructure supplied by government,’ says Goussard. ‘When technology enables this sort of unimpeded growth, it immediately ignites the possibility for investment.’

For example, insufficient banking infrastructure in parts of East Africa inspired the creation of M-Pesa, which enables users to transact and send so-called mobile money by text message, using a very basic mobile phone. Another example is M-KOPA, which was borne out of the need to supply rural communities with off-grid solar power. The Kenyan-based solar-energy company combines M-Pesa technology with internet of things applications to provide solar power to far-flung communities in East Africa.

These stories are not isolated. ‘Various factors are coming together to create investment opportunities,’ says Goussard, who also notes an improvement in governance in many African states.

Peter Baird, managing principal of Africa private equity at Investec Asset Management, says this phenomenon of leapfrogging technology is one of the themes in the African PE space that Investec is particularly keen on. The formation of new industries, which ties in with the above, is another – ‘cross-cutting themes’, as he describes it. ‘As a country’s economy develops, new industries form,’ he says. ‘This is when market leadership is up for the taking.’

To state the obvious, Africa is not a single investment destination, which is why both RisCura and Investec have grouped various African states into investment clusters. These are assembled mainly according to region – Central Africa, East Africa, West Africa, North Africa and Southern Africa – with the exception of a few.

Geographically, says Baird, ‘there are 54 countries in Africa, and out of these 10 are truly investable, 20 are uninvestable, and the rest are in the middle’. Meanwhile, RisCura considers SA and Nigeria as markets in their own right due to their size and specific driving forces.

Goussard explains that RisCura looks for consumer staples as ‘most consumer markets are low-income, and we always want to invest in a product with a large client-base’. Fintech, microinsurance and alternative payment systems are on their radar. Health and education are also very lucrative investments, she notes, especially if you can put your money into private education and healthcare that is accessible to a large portion of the population.

‘There are many private universities opening on the continent, but also small day clinics, many of these funded by PE investments,’ she says. ‘It takes responsibility away from the state. And the minute you supply that function, there’s something to invest in and there’s a demand to be met.’

Goussard suggests that there has recently been increased interest in the rest of Africa ‘because of a general sentiment of reward for risk’.

According to RisCura’s Bright Africa Report 2018, there was a noted reduction in perceived risk in many of the African regions, which is recognised by a decrease in the cost of equity. East Africa has shown a 1% decrease in cost of equity, while Kenya, the largest economy in the region’s risk profile, has remained steady over the year, with Tanzania, Rwanda and Ethiopia all showing a decline in risk. ‘This is the second year in which this region has recorded a decrease in cost of equity, lending some support to the increased asset prices in the region,’ the report states.

Many investors are focused on energy in the East African market, says Goussard, which – bar some political uncertainty – is an attractive investment space. Nigeria, however, continues to be considered a risky investment. Even though it is the largest economy on the continent, it’s been dragged down by the volatile oil price. Yet, as Goussard points out, it’s worth bearing in mind that while the country’s economy goes for a ride every time there’s a dip in the oil price, it flourishes as the price climbs again.

As Baird puts it, ‘we’re all a bit nervous about Nigeria, given the policy confusion and uncertainty but it’s too big to ignore’.

Fund managers are currently looking to infrastructure, project and energy sectors for investments, says Khurshid Fazel, a banking and finance partner at international law firm Allen & Overy. Many of these funds have invested in projects in various sectors, ranging from telecoms (Main One fibre-optic cable on Africa’s west coast), and transport (Lanseria airport, and an airport in Tunisia) to energy (Kenya’s Lake Turkana wind farm). ‘Political climate certainly plays a role but infrastructure projects – including telecoms, roads and renewables – are in high demand and investment into these sectors will continue,’ she says. ‘We’re increasingly finding that PE funds are being set up in the renewable energy space, as it enables alternative fund raisers, seeing that investors from all over the world are happy to invest in green energy.’

Baird argues that for any of these companies to grow, exports need to happen. He adds, however, that the infrastructure industry also has character-istics that are attractive to investors. Most of these projects are dollarised and less exposed to local currencies, he says, and they consider three general themes when investing in Africa – emerging consumers (retail, consumer goods, retail fintech, telecoms and data services); infrastructure companies (transport and logistics companies); and exports, especially of natural resources. He says they look to invest in ‘regional champions’ rather than a company that’s constricted to the borders of one country.

‘This would be a company that has the legs to be a champion across multiple markets,’ he says. One example is IHS Towers, a telecoms infrastructure company of which Investec was the founding investor. IHS is the largest company of its kind in Africa – in other words, it has legs… ‘That’s our archetype of a champion company,’ he says.

Another such, albeit much smaller, champion is Mozambican logistics company, J&J Transport, which imports and exports goods from Mozambique through Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Multiple markets; multiple industries, as Baird says.

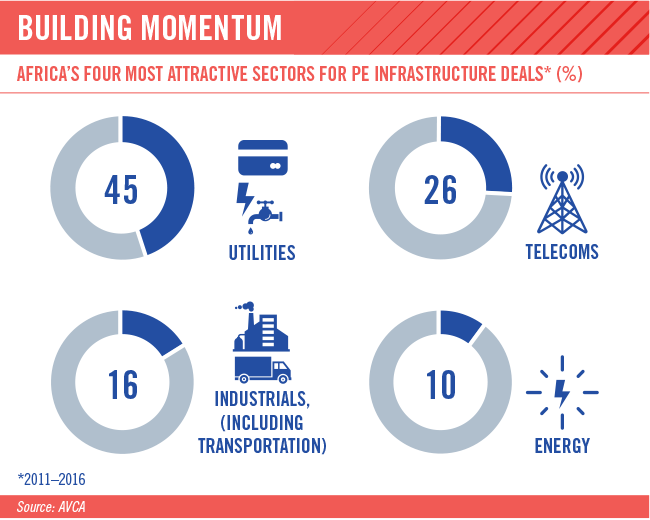

Jeff Buckland, private equity partner at law firm Hogan Lovells, estimates that more than half of the PE funds raised for investment in Africa in 2018 have been around infrastructure development. ‘It’s a key sector throughout Africa,’ he says. According to a 2017 African Private Equity and Venture Capital Association (AVCA) report on Africa’s infrastructure, the total value of PE infrastructure deals on the continent between 2011 and 2016 was $10.6 billion – 86 deals.

In SA, there’s been a shift by many of the fund managers raising new funds to patient capital, says Buckland. ‘There is a lot of competition for the good deals, and while sellers are expecting higher prices, there remains a gap between seller expectation and the buyer value predictions based on the current uncertainties in the country, which requires more patience for optimum exits.’

Goussard says PE fund managers have been very good at finding a niche for growth, and the markets have navigated some very turbulent waters while continuing to perform – a trend that will continue to be the case. ‘The obvious issue to consider at the moment is the changing of visa regulations, which will promote tourism. This, along with the weakened rand, will keep investors interested in the tourism sector,’ she says.

Darryn Faulds, fund manager at Metta Capital, says policy uncertainty has certainly stifled foreign investment into Southern Africa. ‘With South Africa and Zimbabwe both raising red flags with uncertain policy creation, foreign investment into private companies has contributed to a downturn recently in PE activity,’ he says – adding, however, that SA should not only be seen as creating an environment of uncertainty and non-promotion of investment. It launched with amendments in 2015, a Section 12J initiative that offers SA investors a 100% tax-break incentive for investing back into the economy via a SARS-approved structure called a venture capital company. As of February 2018, R3.6 billion had been invested within these structures, which then invest in qualifying SMEs.

Key sectors for investment in SA continue to be retail, services as well as real estate, says Faulds, but there have also been large investments coming into renewable energy projects, agriculture and agri-processing, along with infrastructure projects.

There is still a lag between investments within Industry 4.0 sectors, such as fintech, healthcare as well as IT. ‘This is a worry for two reasons,’ says Faulds. ‘One being that there isn’t a supply of these type of businesses. And the few that are in existence are not receiving equity finance, meaning they will struggle to scale at a rate meaningful enough to contribute to future growth.’

The World Bank forecast in 2017 that the continent’s urban population stood at around 472 million people, with expectations of it doubling over the next 25 years. The AVCA argues that infrastructure investment is crucial in order to translate this rapid urbanisation into sustainable economic development. According to World Bank estimates, $93 billion will be required annually until 2020 to close Africa’s infrastructure gap.

‘PE investors have the opportunity to play a significant role in providing finance to reduce Africa’s infrastructure deficit,’ the report notes.

‘You have all these huge growth themes in Africa – urbanisation, demographic dividend, telecoms, reduced risk premium, emergence of national and regional champions – which, over time, should create great capital wealth,’ says Baird. It’s a sign the big cats may be on the move again.