Monetising biodiversity could mean placing advertising banners in the vast open landscape of SA’s national parks. To commercialise wildlife, selected elephants could be adorned with brand logos, and why not tag some prime examples of big game with collars bearing corporate slogans? Buzzing drones could then capture the branded wildlife from above, broadcasting live feeds to nature lovers worldwide. The big five could be used in product launches or to entertain high-net-worth individuals, who enjoy petting exotic animals and being photographed with them for social media. The country’s pristine protected areas also provide a beautiful setting for large-scale commercial events such as concerts or sports events.

But let’s stop for a moment. While government intends to boost SA’s biodiversity economy, it wants to do this in a sustainable manner to ‘optimise biodiversity-based business potentials’ across economic sectors for the benefit of people and planet. SA is one of only 17 ‘mega-diverse’ countries globally – those with a particularly rich variety of plant and animal species, genetic variations within species, and a wide range of ecosystems. As such, our biodiversity economy ‘encompasses the businesses and economic activities that either directly depend on biodiversity for their core business or that contribute to conservation of biodiversity through their activities’, according to the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE), whose Draft National Biodiversity Economy Strategy (NBES) was gazetted in March 2024.

The draft strategy has been welcomed by some conservation experts, but criticised by others who worry about its plans to increase hunting, bio-prospecting and tourism in order to monetise wild animals and plants for ‘consumptive use’.

Yet, the issue isn’t so much the commercialisation of biodiversity, but the way and the extent of how it is done.

‘We are already putting a value on nature by trading its tangible and intangible services,’ says Shameela Soobramoney, CEO of the National Business Initative (NBI). ‘It must be acknowledged that biodiversity is the foundation of the country’s economy, whereupon almost everything depends,’ she says, citing a recent study which found that 70% of value of goods consumed by households are produced by activities highly dependent on at least one ecosystem service. In addition, 50% of SA’s output is produced by economic activities highly dependent on at least two different ecosystem services.

‘This study refers to the formal economy without paying attention to both the informal and illicit trades of natural resources the world over,’ says Soobramoney. ‘But the use of the word “commoditising” nature is a value-laden term that tends to polarise value systems. This could instead better serve the purpose of underscoring the value of nature by broadening the perspective to view nature not only as a tradable asset but also as providing humans aesthetic and spiritual value too,’ she adds. ‘This makes space for nature’s inherent value to be recognised.’

Nature is an essential public good, and Section 24 of the SA Constitution enshrines everyone’s ‘right to have the environment protected for the benefit of present and future generations’. Until recently, this primarily meant ensuring the sustainable use of our natural resources, protecting the environment from pollution, degradation and other harm, as well as combating illegal plant and animal trade, wildlife trafficking and poaching. The focus is now shifting towards being ‘nature positive’ – actively improving your natural environment (and ‘rewilding’ it). This can, for example, mean reversing nature loss by cleaning up a polluted river, saving an animal species from going extinct or rehabilitating degraded soil. ‘Most of the world’s top 500 companies have a climate target, but just 5% have one for biodiversity,’ states the WEF’s Nature-Positive report series. ‘Given how dependent the global economy is on nature, the private sector urgently needs to help halt and reverse nature loss this decade.’

The DFFE supports the ‘30 by 30’ target of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which strives to conserve at least 30% of the world’s land and sea area by 2030. In line with this, SA’s draft NBES plans to increase the areas under conservation from 20 million ha to 34 million ha by 2040. But less than a third (4.2 million) of the additional 14 million ha is earmarked as protected areas and the bulk of the land (9.8 million ha) will be set aside for ‘other conservation measures’ (for example, bioprospecting, ecotourism, agro-foresting or sustainable hunting and game farming).

‘We support conservation practices that, within the scope of the law in SA, promote the ecologically sustainable use of wild animals in natural free-living conditions to the benefit of all,’ says Kishaylin Chetty, senior manager of sustainable financing and business partnerships at the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT).

He explains that the fundamentals of the DFFE’s draft strategy have great alignment with the EWT goals and provide a platform to continue the discussion with government. While more clarity is needed on several of the listed actions in the draft strategy, Chetty says the EWT will keep on working with the department to constructively unpack and resolve any areas of concern.

‘There are a multitude of avenues where South Africa can reap economic and social benefits from biodiversity, but we continue to see ecotourism as a sector that can stabilise and grow socio-economic opportunities to the benefit of all South Africans,’ adds Chetty. ‘We are working with a number of private sector and government entities to develop and pioneer initiatives that both support the ecotourism sector and ensure appropriate conservation of our ecological assets.’

The Drylands Conservation programme is such an example. The EWT has been collaborating with local communities and landowners in the Karoo to legally secure private land and conserve dryland habitats and species.

In Papkuilsfontein near Nieuwoudtville, Northern Cape, the programme established more than 100 km of mountain bike and trail running routes. This ecotourism venture allows farm-owners to explore alternative nature-based income streams while conserving an area at the convergence of the Fynbos, Succulent and Nama Karoo biomes that is exceptionally rich in plant biodiversity.

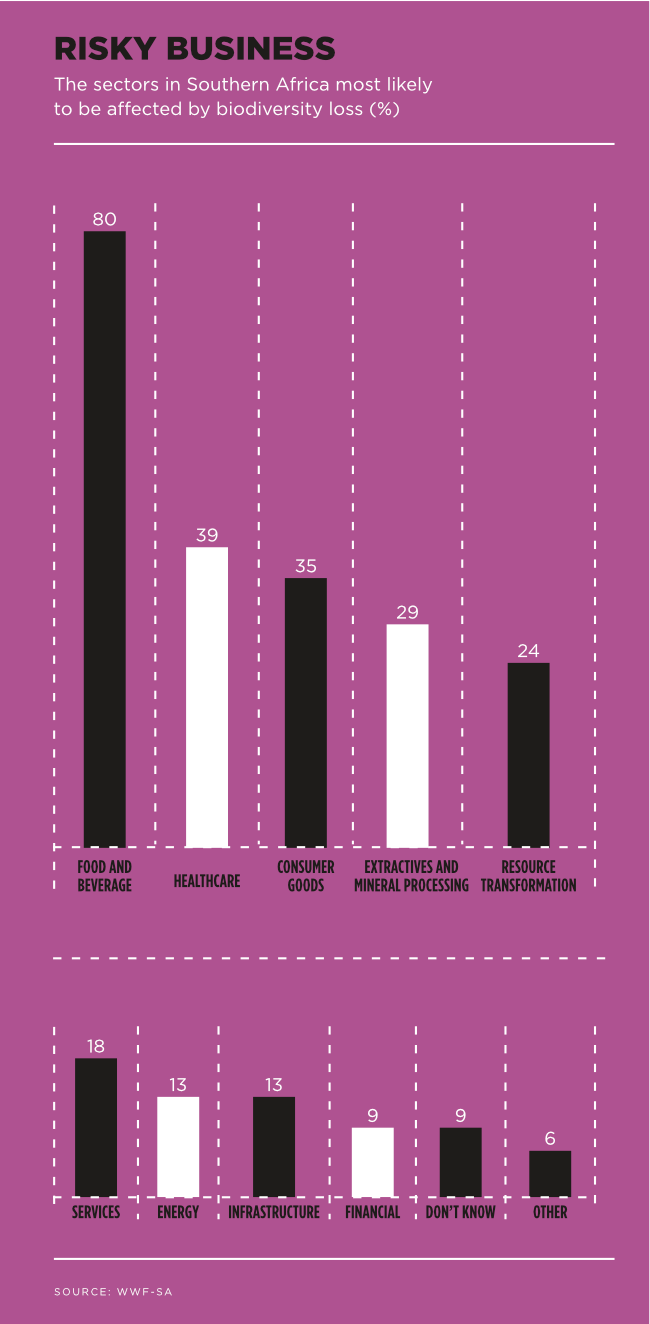

One of the greatest challenges – not only for NGOs – is unlocking new biodiversity funding. ‘More than $44 trillion in economic value is at risk from nature loss globally and the financial sector has a critical role to play in capital allocation to shape this trajectory,’ says Justin Smith, head of business development at WWF South Africa. But unlike climate, he says, there is still some uncertainty about how best to prioritise actions to address the impacts of nature-related risks.

The NBI’s Soobramoney explains that at the Bonn Climate Change conference in June 2024, UN Environment Programme officials highlighted that $200 billion is currently flowing to nature-based investments each year. ‘This is less than a third of what is needed per year by 2030 to meet climate, biodiversity and land degradation goals,’ she says.

‘More troubling, however, is that this figure is eclipsed by the $7 trillion in nature-negative finance that flows annually from harmful subsidies and investments.’

To diversify opportunities and grow larger amounts of funding (on top of conventional sources such as philanthropy, government funding and grant funding), Chetty says his organisation is trying to ‘bring in different types of funding to stimulate the growth of our species conservation work’. It does this by looking into conservation market-based instruments and finance mechanisms such as carbon markets, biodiversity offsets and social conservation impact bonds, as well as wildlife impact bonds.

The EWT has, for example, partnered with Rand Merchant Bank to develop wildlife bonds, which Chetty describes as ‘a sustainable finance instrument that enables large funding to come from asset management investment to drive outcomes-based conservation that speaks to species-related work’. In this case, the wildlife bond is expected to raise between R100 million to R150 million to fund the conservation of wild dogs and lions.

This follows the world’s first wildlife conservation bond, which was also launched in SA. The $150 million ‘Rhino Bond’, issued by the World Bank in 2022, intends to grow the population of the endangered Black Rhino species in SA. ‘Sustainable development bonds are outcome-based, financial instruments that direct investments to achieve outcomes in conservation as the case is for the “Rhino Bond” but can also be designed to achieve landscape-scale impact,’ says Soobramoney, before explaining another innovative biodiversity finance method. ‘In South Africa, BirdLife and others began testing biodiversity tax incentives a few years ago as a benefit for landowners declaring protected areas, through the Biodiversity Stewardship model,’ she says.

‘The test was successful and so a new tax incentive, Section 37D, was introduced into the Income Tax Act. It enables the value of a nature reserve or national park to be deducted from taxable income, reducing the tax owed by a landowner.’

While this is a niche incentive, the DFFE has also launched an online portal that targets a broader market. The Biodiversity Sector Investment Portal aims to introduce and match nature-based investment opportunities to the appropriate investors and intermediaries in SA. Current projects seeking invest-ment range from a community farm in Mpumalanga wanting to expand its Nguni livestock and bioprospecting offering, to eco-tourism lodges, biodiesel production, and a social enterprise geared to produce charcoal from alien invasive species while improving water security in the Eastern Cape.

All these biodiversity initiatives and finance mechanisms are at the nexus of socio-economic development and biodiversity management, with a strong focus on nature conservation. It seems that SA’s wildlife is safe from being branded with corporate logos, for now.