The slogan ‘Don’t buy this jacket’ has worked well for US outdoor clothing and gear company Patagonia. The seemingly contradictory advert grabbed headlines when it encouraged customers to think twice before buying.

‘To lighten our environmental footprint, everyone needs to consume less,’ the California-based company says. ‘Businesses need to make fewer things but of higher quality. The test of our sincerity, or our hypocrisy, will be if everything we sell is useful, multifunctional where possible, long lasting, beautiful but not in thrall to fashion. We’re not yet entirely there.’ But the company has been working on getting ‘there’ – and it’s been vocal about it.

Since the ‘Don’t buy’ ad campaign in 2011, the brand has positioned itself further as a green trailblazer and ‘activist company’. Its website reads like a curious mix between a commercial, for-profit business and a non-profit organisation that fights for clean water, air and land.

Patagonia doesn’t see this as a contradiction. While the company clearly states that it is ‘in business to make and sell products’, it wants to do this in the most ethical, least harmful way possible. The logic behind this is that its outdoor products enable customers to enjoy the natural environment, so there’s a vested interest in conserving it. But, more importantly, to be a genuinely green company, you need to understand that the destiny of your business is deeply interconnected with the state of the natural environment (and the society) around you. Anything else and you may stand accused of greenwashing.

Patagonia takes this to the extreme in that it declares the protection and preservation of the environment to be ‘the reason we’re in business’.

For most green brands, environmental progress goes hand-in-hand with socio-economic development and good corporate citizenship, which is why there’s been a shift from ‘green’ towards using the broader term ‘sustainable’.

Eric Whan, director at sustainability consultancy GlobeScan, explains the correlation, saying: ‘Leadership companies are seen as those that align their sustainability strategies and their internal culture and values. Their social, environmental and business purposes work together towards the same impact, powered by clear goals and the innovation required to achieve them.’

His consultancy, in partnership with the think-tank SustainAbility, publishes the annual Sustainability Leaders Survey, in which multinational brands such as Patagonia, Unilever, Ikea, Tesla, Nestle and Nike rank at the top. In the African region, Woolworths typically leads the way.

Nikki Griffiths, fund management executive at Tshikululu Social Investments, says that to ‘maintain your status as a green brand, you have to be in the forefront of driving change and innovation in issues of environmental progress. This also speaks to a brand’s green status being authentic – and genuinely about caring for the environment’. She adds that for the majority of SA companies considered green brands, environmental progress goes hand in hand with socio-economic development. ‘If a company cares about environmental development, they are more likely to want to influence the communities to do the same.’

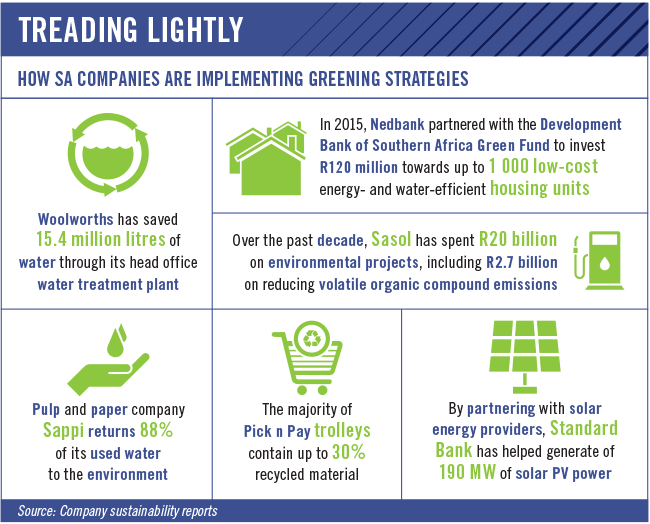

There’s a growing number of SA companies making impressive progress with their green initiatives but they don’t always receive the spotlight they deserve. They include South African Breweries (SAB), Sappi, Nedbank, Standard Bank, Santam, Sasol and Pick n Pay, among others. SAB – now the local business of AB InBev – is a pioneer in the use of water footprints to calculate the water usage in the beer value chain, from crop cultivation, processing and brewing to distribution and disposal. The brewer has reduced its water consumption from 4.5 litres of water per litre of beer in 2009 to 3.2 litres in 2016, and (before the merger) had plans to push this further down to 2.89 litres by 2020.

AB InBev updated its ‘Better World’ strategy in October 2016 after the merger to align its global environmental, social and alcohol responsibility initiatives across all operations. Group CEO Carlos Brito has committed to securing 100% of purchased electricity from renewable sources by 2025, which will reduce the operational carbon footprint by 30%.

SAB has also played a leading role in the Strategic Water Partners Network SA, a joint effort with government and private companies (such as Sasol, Nestlé, Rand Water and AngloGold Ashanti) to mitigate shared water risks.

The ability to foresee and manage environmental risks is crucial for any green brand. Insurance company Santam has come up with an innovative Partnership for Risk and Resilience initiative in which it equips vulnerable municipalities to efficiently deal with natural disasters such as fires, storms and flooding. This mitigates the potential impact on the firm’s own business through fewer insurance claims while simultaneously keeping down the premiums for the insured clients.

According to Donald Kau, Santam’s outgoing head of corporate affairs: ‘In George, we have sponsored an early warning message system linked to the Eden District disaster management centre, which assists with the transmission of warnings of severe weather conditions and disaster notifications to the public.

‘In another example, the research done on our research and experimental farm looking at the effect of hail damage of crops allows for the results of hail damage simulation to be compiled, and for us to update procedures and tables according to which the actual damage suffered by insured farmers is determined and settled following hail storms.’

On the banking front, Nedbank’s positioning as SA’s ‘green bank’ started as early as 1990, when it was still a niche market. Through its WWF Nedbank Green Trust and Green Affinity programmes, the bank built up a solid green reputation, supporting a wide range of causes (related to, for example marine, freshwater, land stewardship, species of special concern and climate change). The trust engages closely with local communities through environmental leadership training, as it says people are the custodians of ecosystems.

Meanwhile, Standard Bank is focusing its environmental efforts on ‘conscious lending’ for the renewable energy sector. November 2016 saw the launch of its social economic environmental (SEE) framework, which supports solar energy projects – in addition to helping another environmental cause, namely restructuring loans for drought-impacted farmers, thereby keeping just under 50 000 ha productive in 2015/16.

By partnering with solar energy providers, Standard Bank has facilitated the generation of 190 MW of solar PV energy, which is enough to provide 92 500 homes with clean power.

‘I participate in the direct management of environmental factors that can affect the bank,’ says Kgubudi Breyten Mojapelo, an environmental management systems analyst at Standard Bank, in the 2016 Report to Society. ‘These factors include resource use (energy, water, paper, waste), regulations and legislation (carbon tax, environmental impact assessments, waste pricing), responsible procurement and carbon footprint.’

He adds that ‘the risk posed by these factors can include reputational risk and financial risk (penalties and fines). Driving Africa’s growth means I can help the bank look at opportunities in the green space, which includes opportunities in carbon trades, carbon offsets and assisting in climate finance for the facilitation of a green economy’.

Such dedicated employee buy-in and personal investment is invaluable for the success of a green brand. And it’s good PR to talk about it.

That’s also one of the secrets behind Woolworths’ systemic environmental connectedness. For the past 10 years, the retailer has based its Good Business Journey on storytelling that explains the complex environment, social and governance risks in an easy-to-understand, non-patronising way. This has helped motivate staff and customers to work together in ‘reducing, reusing and recycling’, and even strive for a greener lifestyle at home.

Woolworths is an excellent example of corporate transparency underpinned by high-profile marketing campaigns that share the green lessons the company has learnt. Pick n Pay has also started storytelling on its website, illustrated with photos and YouTube clips, to keep customers, staff and others up to date with its Sustainable Living initiative that includes, among others, its war-on-waste campaign.

This trend also plays a role in the textile industry where fashion retailers are reducing waste by recycling clothes – and talking about it. European fashion chain H&M has collection points for unwanted garments of any brand, which are then made into new clothing lines. Its Close the Loop commercials to publicise the initiative have proved hugely successful. Denim brand Levi’s is also en-gaging consumers directly, asking them on social media to wash their jeans less frequently to save water, and to buy the first Levi’s 501 made from recycled cotton T-shirts. The firm’s vice-president of sustainability, Michael Kobori, says: ‘Effective sustainability storytelling must move beyond the “save the planet” messaging that frankly has not engaged most consumers. We have the oppor-tunity to use our relationship with our fans to make sus-tainability fun, cool and something that comes naturally to people. We want to make sustainability effortless.’

Back at Patagonia, it’s been authentic, interactive ‘fun’ for a while. The Footprint Chronicles were launched in 2007, allowing consumers to follow the origin of each garment throughout the supply chain, from the textile mill to the sewing factory. Those who spend time viewing these ‘stories other companies typically don’t tell’ will understand that the advertising slogan actually meant ‘don’t buy this jacket, unless you really, truly need it’.

That’s the essence of green brands – they have decoupled economic growth from their environmental impact. So they still want your money but steer you towards ethically made, high-quality goods that will last longer and are therefore gentler on the planet.