The Encyclopaedia Britannica entry is succinct… Corrado Gini, (born 23 May 1884, Motta di Livenza, Treviso, Italy – died 13 March 1965, Rome), Italian statistician and demographer. The name, to the vast majority of humanity, doesn’t mean a thing (unless you’re an economist). His work, though, is another matter. Gini was the originator – in 1912 – of the Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality.

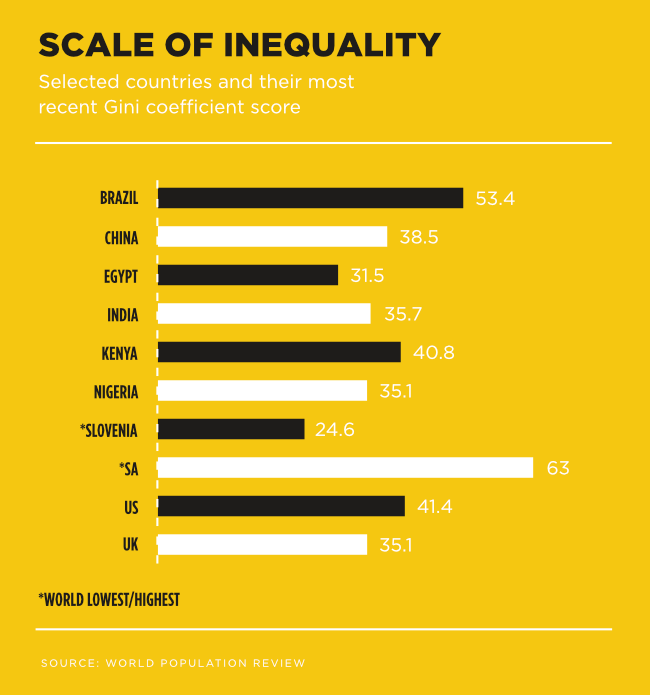

‘It is a way of comparing how distribution of income in a society compares with a similar society in which everyone earned exactly the same amount. Inequality on the Gini scale is measured between 0, where everybody is equal, and 1, where all the country’s income is earned by a single person,’ as per the BBC, is a simplified definition of the ratio.

The more the Gini, the greater the degree of inequality in a country. SA, according to the most recent data, has a Gini coefficient of 63 – the highest in the world. SA’s complex history has left a legacy of socio-economic challenges, some of which are being addressed by CSI.

The country has a diverse population with stark disparities in income, access to education, and healthcare. This diversity often translates into differing expectations and demands from various communities. Corporations must navigate this intricate web, which can be particularly challenging when attempting to develop a comprehensive CSI plan that satisfies all stakeholders.

ESG factors have become of pressing concern to business in recent years, but many experts are framing ESG in terms of this question: should SA be concentrating more on the ‘S’ than the ‘E’ and the ‘G’? Would that be the right strategy to tackle the country’s inequalities?

‘While environmental concerns often dominate discussions in boardrooms and C-suites around the world, many organisations pay less attention to social issues and how these impact their organisations and their ability to govern for sustainability. It has become vital for new-age leaders to gain a deeper understanding of the social dynamics and processes that influence economic activity,’ says Francois Laurens, an adjunct faculty member at the Gordon Institute of Business Science.

‘In South Africa, several specific societal issues are particularly pertinent to the ESG framework. These include inequality, unemployment and poverty, labour relations, access to basic services, education and skills development, healthcare, HIV/Aids, community engagement, political stability and governance, diversity, equity and inclusion, youth empowerment and employee well-being. It has become vital that companies in South Africa actively work towards redressing these historical imbalances to ensure that the situation in South Africa improves and that the economy becomes more inclusive. This offers a framework to generate economic growth, achieve social justice, exercise environmental stewardship and strengthen governance.’

Dipalesa Mpye, head of social impact at Tshikululu Social Investments, says the backdrop of the enduring impact of poverty, unemployment, in particular youth unemployment, and inequality in SA remains significant to how companies and organisations approach ESG. ‘As it stands, we have made varying levels of progress towards the SDGs, but major and significant challenges remain across all of them, with COVID having also eroded progress made to date. This is the challenging operating environment within which ESG strategy, initiative design, implementation and risk management needs to be framed. Businesses don’t operate in a vacuum but are located within a social context, that ultimately impacts on a company’s growth and sustainability.’

She cautions, though, against a skewed emphasis towards societal investment only, saying that the ‘interconnected nature of E, S and G is amplified in our context, which demands a holistic approach. We have to consider seriously, for example, how issues around biodiversity impact on community well-being and livelihoods, and we cannot drive impact under the E or the S without sound governance’.

Recent research from Henley Business School Africa in collaboration with data science and risk management firm Risk Insights echoes this point. ‘When we mention different world views and mindsets [in the research], we specifically refer to the mindset of shareholder value maximisation versus the mindset of sustainable value creation, but also to the Global North versus Global South debate and issues like climate justice,’ according to the organisations’ findings. ‘There’s a shared view that South Africa and other developing countries have less of a moral obligation to tackle climate change urgently as the problem has been born by the rich Global North. Consequently, the dominant understanding is that for South Africa, the priority is the “S” or social in ESG, as this is where there are more significant and pressing challenges. Tackling environmental issues with vigour may mean less ability to resolve social issues. However, the opposite is also true – as social gets prioritised, the inability to tackle environmental concerns may mean a loss of competitive advantage or constraints in exporting goods and services to more mature markets, in turn impacting social issues, such as employment. These views were found to permeate business leaders and determine how ESG is pursued.’

Experts have found that company approaches to address societal factors vary by sector and the nature of business operations, but the benchmarks remain regular measurement and evaluation of a corporate’s impact of CSR initiatives. This allows corporations to adjust their strategies based on evidence and ensure that resources are effectively allocated.

Mpye says companies must effectively engage with local communities and stakeholders to ensure their ESG initiatives are aligned with current societal needs and expectations. ‘Before effective engagement can take place, companies need to invest in understanding the communities within which they operate through comprehensive stakeholder mapping, and this is also not a once-off exercise. Undertaking community needs assessments and baseline studies are crucial tools. These are studies that assist in ascertaining the assets/resources, challenges and needs within a particular community. We have conducted these for several of our clients within the mining and renewable energy sectors and have found them to be valuable for laying down a foundation for alignment and mitigating against duplication of efforts.’

She says companies typically encounter certain challenges when trying to address societal aspects of ESG in SA. ‘These are usually around on-the-ground implementation of “S” initiatives within communities and being able to reliably report on impact beyond inputs and outputs. What is needed is threefold – multidisciplinary partnerships that include government, civil society, academia and business; an investment into the grassroots community ecosystem by way of strengthening the technical capabilities and capacities of community-based organisations, so that they can drive sustainable impact as these organisations play a critical role in being responsive to community needs and are key stakeholders when it comes to conflict resolution; and intentional allocation of resources towards designing for impact upfront, with the need for impact measurement and monitoring so that impact can be understood, managed and effectively reported on.’

Corporate SA, though, is just one part of the equation – other stakeholders such as government, NGOs, academia as well as communities and civil society will need to collaborate closely with business, according to Mpye.

The Henley/Risk Insights report says there ‘needs to be a true partnership between government and corporate South Africa in creating the conditions – i.e. the regulatory framework, infrastructure and legal mechanisms – to enable firms to have the baseline conditions and complementary assets to deploy effective ESG strategies that can create long-lasting value’.

And it’s not just communities and employees whose needs must be attended to – these days companies are expected to take stands on social topics that sometimes go well beyond the products and services they provide.

‘The shift in expectations for organisations to take a stand is driven by several factors,’ says Laurens. ‘Consumers are increasingly conscious of social and environmental issues. They prefer to support companies that align with their values and take a stance on important societal matters. Brands that remain silent on important issues risk being perceived as indifferent or complicit. Employees, especially from younger generations, often seek out employers that are socially responsible and actively engaged in addressing societal challenges.

‘However, organisations need to approach this with authenticity and caution. Companies should genuinely care about the issues they support and take concrete actions that align with their values. Companies should choose issues that are relevant to their industry, values and expertise. Companies should maintain consistency in their stance and actions over time. Flip-flopping on issues can erode trust. Moreover, taking a stand without a deep understanding of broader sentiment is risky, especially as value systems differ from person to person, and ethical and moral values are shaped by factors such as culture and religion.’

It’s not only complex … what becomes patently clear is that addressing societal issues in a country with a high Gini coefficient is a long-term endeavour. Corporations must demonstrate a sustained, co-ordinated effort to these initiatives, combining transparency with a dedicated commitment to making a positive and long-lasting impact on society.