Decades from now, historians will look back on November 2016 and wonder what was going on with the world. The Brexit-battered EU was reeling from the results of the UK’s EU membership referendum. In the US, voters were electing a president whose first order of business would be to formally scrap the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a flagship trade deal with 11 Pacific Rim countries.

Meanwhile in Africa, ministers and negotiators from across the AU were meeting in Addis Ababa for a fourth round of negotiations to establish a Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA). While border walls seemed to be going up and trade blocs appeared to be crumbling all about us, Africa was pushing forward with what would constitute the largest free-trade area in the world.

If those negotiations ultimately prove successful, the CFTA will comprise 54 member states, more than 1 billion people (ballooning to 2 billion or more by 2050), and a combined GDP of more than $3 trillion.

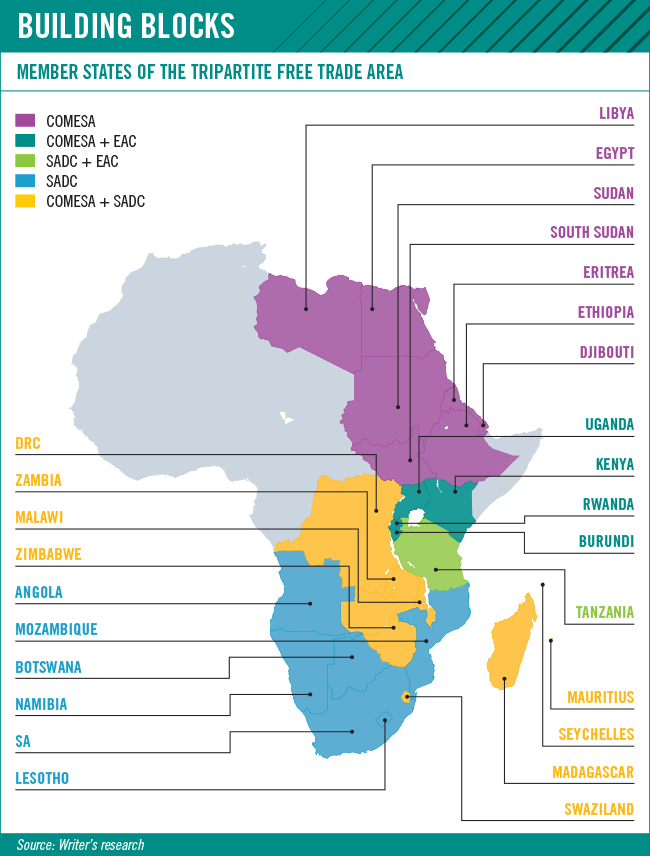

The CFTA already has a solid base to build on, following the establishment of the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) in June 2015. The TFTA deal aimed to convert three African trade blocs – the EAC, SADC and COMESA – into a single customs union. The TFTA’s Cape to Cairo free-trade area covers 26 member states, with a combined population of 625 million and a GDP of $1 trillion – or 51% of Africa’s entire GDP.

Speaking ahead of the TFTA meeting in Sharm el Sheikh, Egyptian Minister of Industry and Trade Mounir Fakhri Abdel Nour told delegates that the agreement would be a ‘monumental step’ for the continent. ‘It will bring together a united Africa,’ he said, calling the deal ‘a big step towards achieving the continent’s dream. It will help in strengthening our bargaining power, create jobs and raise standards of production’.

The TFTA is the first move in what many African leaders hold to be the ultimate vision of a united Africa. Following the path mapped out on a regional level by SADC, the next step after the continent-wide free-trade area would be a customs union, then a common market, then a monetary union and then, finally, a single currency.

Still, one can’t help but look north to the EU and its constant threats of Brexits, Grexits and Nexits. ‘The European experiment is under huge pressure,’ says Jannie Rossouw, head of the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Economic and Business Sciences. ‘If you look at the euro at this point in time, I’m not so sure a common currency among countries with large diversity is the best option. I think you can have a common currency where one huge player like South Africa pulls the others along, or you have countries of fairly similar size, with fairly similar levels of development. Or you can have what we have down here in the CMA [Common Monetary Area] where South Africa accounts for 95% of the economy, and basically carries countries like Lesotho and Swaziland. You can’t have economies all over the place and then not expect the big one to carry the small ones.’

The problem goes further. ‘All that’s keeping the Southern African Customs Union [SACU] together is the huge transfer payments going from South Africa to the other partner countries,’ says Rossouw. ‘Swaziland’s government income basically comprises SACU transfer payments from South Africa. The country is not fiscally viable without South Africa.’

Still, despite the challenges, there’s a strong case to be made for breaking down the trade barriers that exist on the continent, as Thomas Verryn, research manager for sub-Saharan Africa at Euromonitor, explains. ‘Some of the challenges faced in the past still remain relevant, and these would include the diversity of the different economies and lack of physical infrastructure,’ he says. ‘In order for the trade blocs to be effective, a regional and a global focus will be important. Too strong a focus on regional trade could compromise potential global opportunities for member states.’

Verryn adds, however, that ‘despite African trade blocs not always having performed as well as expected, the potential benefits of the Tripartite Alliance are obvious through the reduction of regional trading barriers. These include protection of local products against cheap imports and increased regional and global trade – and lower costs, increased bargaining power and potential political and administrative reforms will result in increased foreign direct investment’.

At a media conference in January, Fatima Haram Acyl, AU Commissioner for Trade and Industry, highlighted the fragmented nature of Africa’s markets and said that the continent-wide CFTA would ease movement of goods and people across the continent, and help attract huge amounts of investment. ‘Africa needs to focus on its own priority, its own market, its own people, the employment of people, the prosperity of this continent,’ she said.

Speaking later to the Financial Times, Acyl dismissed concerns about the global move away from regional trade blocs. ‘If you look at the EU, at Brexit, they have already the industrialisation,’ she said.

‘They’re powerful countries that have integrated but now maybe they’re going in different directions. That’s not the case for Africa. We need each other. We need to integrate. We’re too small, too fragmented to have a voice anywhere. We need it to attract a huge amount of investment.’

The problem, however, is that despite what Acyl said, Africa is also too large and too interconnected to function smoothly. It’s such a diverse continent, and the needs of African countries differ so much that a united continent seems hardly achievable. ‘The needs and requirements of these countries differ so substantially that you cannot have a single approach for Africa,’ says Rossouw.

‘What is good for Botswana is not necessarily good for Swaziland – and they’re in the same sub-region. What is good for Botswana can’t be good for Nigeria, because Nigeria is a major oil producer and Botswana is a diamond producer. You have to take this into consideration.’

Adding to the complexity, the vast majority of Africa’s 54 countries are members of at least one of more than 30 overlapping sub-regional and regional economic groups. Some analysts call it a spaghetti bowl. Rossouw refers to it as an African fruit salad. He pulls out a diagram showing Africa’s various regional trade alliances. It’s complicated.

‘Look at all the structures within Africa and you’ll see the high degree of overlap,’ he says. Then comes the fruit salad – or alphabet soup. ‘COMESA and SADC have fairly similar membership but then you have Libya, which is in COMESA, AMU and CEN-SAD – but not in SADC. Then you have Kenya, which is part of COMESA and also CEN-SAD and IGAD.

‘Then there’s Angola, which is part of ECAS and SADC but not COMESA. So you have this high degree of overlapping membership.’

That overlap, Rossouw says, is a huge barrier to creating a viable customs union. ‘You will note that Swaziland is part of COMESA and Namibia is part of CBI,’ he says. ‘But those two regions have neither monetary unions nor customs unions at the moment. So it could work. But then you can’t be part of two monetary unions, and both Namibia and Swaziland are members of SACU, CMA and SADC, and they are part of a common monetary union.’

And so it goes on. This country is part of that group, which includes a country that is also part of another group, which includes another country that is part of another group that does not include the first country. And this happens all over the continent – much to the confusion of anybody looking at Rossouw’s complicated Venn diagram.

‘You can’t call yourself a trade bloc when you still have the problem of overlapping membership,’ he says. ‘You can have trade blocs within a trade bloc – like, for instance, SACU within SADC, or CMA within SADC – but if you want to move to a customs union you cannot have a SACU member who is also a member of another trade bloc. If you do, you have leakage between these blocs.’

Despite – or perhaps because of – all those regional groupings, free trade between African countries isn’t really happening at the moment. Experts are quick to point out that intra-African trade is the lowest of any region in the world, at about 10%. Intra-regional trade in Europe is 60%, while within South-East Asian nations it is 30%, and in South America it is 21%.

Speaking to Rwanda’s New Times at the sidelines of the Global African Investment Summit in Kigali last September, COMESA secretary general Sindiso Ngwenya said that the TFTA would have trade values worth more than $50 billion – bringing a welcome boost to a continent with low levels of intra-regional trade.

‘For example, in COMESA our trade from products being traded within the region stands at around $11 billion, whereas products being imported to the same countries stand at about $90 billion,’ he said. ‘This shows we need to change something.’