SA’s oldest coal power plant has puffed its last carbon emissions into the Mpumalanga sky. After six decades of burning coal, Eskom’s Komati power station was decommissioned in October 2022, with its smoke stack towers soon to be upstaged by solar panels, wind turbines and battery-power installations. It’s the first project in the country’s Just Energy Transition – from a coal-fired economy to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 – and also the first project financed by a $497 million World Bank concessional loan for SA.

This is a big step in the Just Energy Transition (JET), where ‘just’ refers to the objective of not leaving behind any workers, communities and others severely affected by the decarbonisation of the economy, especially the phasing out of coal. Aligned to this, Eskom said no jobs would be lost at Komati. The state-owned utility has partnered with the South African Renewable Energy Technology Centre of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology to establish the Komati Training Facility to develop renewable-energy artisans and technicians. The goal is to educate, reskill and upskill the remaining Komati employees as well as qualifying community members, and become a model for reskilling programmes at other power stations, as well as to catalyse JET investment.

Securing finance and investment plays a massive part of the JET, and climate-change adaptation and mitigation in general. There’s a need for grants (which don’t need to be repaid) and concessional loans (with below-market rate interest) rather than the more expensive commercial lending. Kesh Mudaly, Johannesburg-based principal at Boston Consulting Group (BCG), says ‘it is critical that the terms of those financing agreements become more acceptable for developing countries, so that they don’t lead them further into debt or, worse, erode the fiscal strength of the country’.

SA’s newly released JET implementation plan (JET-IP) puts the country’s just transition cost over the next five years at R1.5 trillion – a funding gap of R700 billion or 44%. The money is needed to shut down further coal power stations, fund solar, wind and other renewables, and to prioritise investment in the electricity, electric-vehicle and green-hydrogen sectors. The plan was made public in November 2022, just before the UN’s annual international climate conference, COP27, held for the first time in Africa (Egypt). Billed as the ‘implementation COP’, it was actually a ‘finance COP’, says law firm Norton Rose Fulbright. ‘Not because of the actual financial commitments made, but because it has underlined that finance is the most important factor in transforming climate ambitions into reality.’

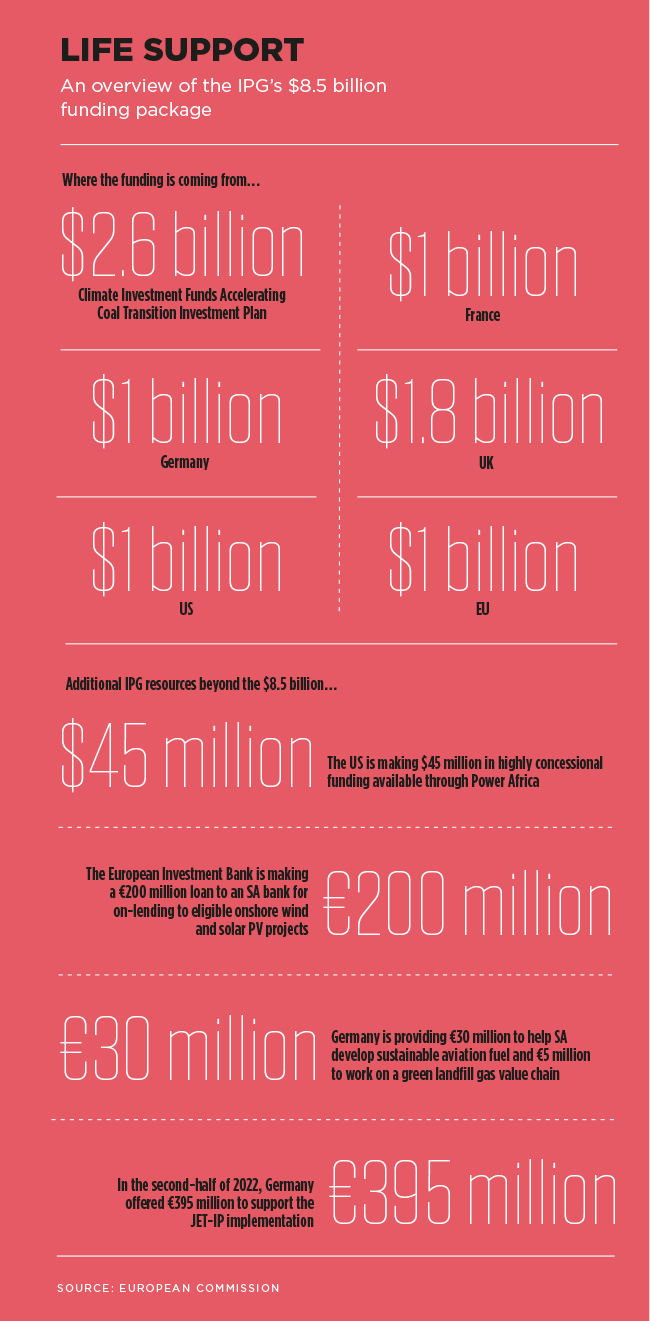

At the previous event, COP26 (Scotland), SA emerged as a trailblazer for other developing nations when it attracted $8.5 billion in transition-finance pledges from France, Germany, the UK, US and EU (known as International Partner Group – IPG). The announcement was followed by nearly 12 months of silence, before the partners issued a joint statement to endorse the JET-IP. Furthermore, it said that some IPG grant funding had contributed to the development of the IP. For example, Germany funded the integration of solar energy into the existing power grid; France contributed to the development of a climate finance mapping and tracking tool; and the UK funded the development of a just transition plan for the two most coal-dependant municipalities in Mpumalanga.

Over the next five years, SA’s JET-IP is allocating $7.6 billion (of the pledged $8.5 billion) to electricity infrastructure, $700 million to green-hydrogen projects and $200 million to the electric-vehicle industry. The $497 million Komati project, financed by the World Bank, is additional to this. ‘SA’s investment plan is a robust, coherent plan that goes beyond large-scale infrastructure and centralised projects,’ says Mudaly. ‘About $16 million will go into social investment and inclusion, which speaks directly towards community impact and mitigating the risk there.’

Another $22 million will go towards innovation and economic diversification, which could enable NGOs, civil society and academia, and $12 million is earmarked for skills development, which will play into community support. ‘Each of these projects will have a strong localisation angle to drive inclusive industrial growth.’ He adds that ‘many developing countries have commended South Africa on its pioneering role and are looking to follow our example’.

Unfortunately, wealthy countries haven’t upheld their long-standing pledge to deliver $100 billion annually to developing nations. In 2020, they mobilised $83.3 billion, $33.2 billion of this from multilateral development banks (MDBs). Mudaly speaks of an increasing push to reform global financial institutions, such as the World Bank and IMF, as they are no longer fit-for-purpose to respond to the climate crisis.

‘MDBs need to be set up to fund new green economic industries, such as hydrogen, and the social projects to ensure nobody is left behind in the transition, while also scaling up large scale infrastructure projects,’ he says.

This year’s summit provided mixed results. ‘The goal of limiting global average temperatures to 1.5°C by 2100 remains, but it’s very unlikely, given that emissions must fall 45% by 2030 but are set to rise 11%,’ according to BCG, the exclusive COP27 consulting partner. On the upside, the summit elevated the concerns of the developing world, with the most important outcome being the last-minute agreement for a ‘loss and damage’ finance facility.

‘Loss and damage are the costs of climate change that go beyond what countries can adapt to and mitigate against,’ says Irene Lauro, environmental economist at Schroders. ‘It has always been a highly controversial issue –richer countries have been concerned about liability claims for climate damage caused by their emissions. However, much of the detail still needs to be defined. For example, the UN text does not include how much money will be provided in the fund. A committee with representatives from 24 countries will need to decide who contributes to the fund and who will benefit from it.’ In theory, SA – as a high emitter – could be asked to contribute rather than benefit from the fund.

Then there’s the Global Shield, launched by the G7 group of wealthy nations and backed by the V20 group of vulnerable countries. ‘This is a new insurance-based mechanism that will provide poor and vulnerable people with better pre-arranged finance against disasters,’ says Lauro, adding that, so far, the total promised is around $282 million, with Germany being the largest contributor, committing to $178 million.

‘Those who will suffer most in the climate breakdown are not the countries that can afford adaptation, but the developing countries, which – through no fault of their own – will take the brunt of this,’ says Jon Foster-Pedley, dean and director of Henley Business School Africa. ‘We are already starting to experience extreme temperatures and drought in Southern Africa. The only bulwark against desertification, water and food insecurity is development that is led and sustained not by foreign aid, but through indigenous business.’

Africa’s business schools also play an important role in this, according to Foster-Pedley, who – as chair of the Association of African Business Schools – attended the Deans’ Roundtable in Cairo during COP27. The event saw the launch of the African iteration of Business Schools for Climate Leadership, an initiative started by eight leading European business schools during COP26. ‘I think we could ramp it up even further,’ he says. ‘Rather than helping businesses adapt to climate change and make money in adapting to climate markets, business schools need to become activists to prevent this happening in the first place.’

In fact, he urges everyone to take climate action, in line with UN secretary-general António Guterres’ warning at COP27 that ‘countries across the world face a stark choice: co-operate or perish’. SA has taken a strong stand and will need further co-operation – and additional finance – to make the just transition to a better future.