The time may come when historians of mining in SA look back at 2019 as a critical turning point. The industry appears to have turned a corner with rosier results reported by some of its previously beleaguered listed companies.

At the same time, headwinds such as the expensive and insecure electricity supply continue to plague it. Despite this, 2019 saw the emergence of promising signs in a number of smaller projects and less-glamorous minerals.

The recent load shedding that began in December struck a sector that has shown greater signs of resilience in 2019 than it has done for the past decade. Listed companies have finally begun consistently making money again after a poor series of results going back to 2011. When national power utility Eskom announced unprecedented Level 6 load shedding on 9 December – shutting down Sibanye-Stillwater, Impala Platinum and Harmony Gold, among others, it hit companies that had the financial reserves to cope with the crisis. They also have the capacity to contribute to solving it if the hurdles to independent power production can be removed.

Deep-level, hard-rock mining is an energy-intensive activity. Electricity makes up 19% of Sibanye’s operating costs, for instance, up from the 9% the company’s three operational gold mines spent in 2007. The deep shafts in platinum and especially gold mining have massive cooling requirements, not to mention the costs of their vast lifting and underground transport needs.

The deepest gold mine, AngloGold Ashanti’s Mponeng, runs about 3 400m underground, a depth at which, without cooling, temperatures reach 55˚C.

Although the financial recovery of the country’s corporate mining sector should not be exaggerated, deep-level operations did do much better in 2019. Gold Fields’ South Deep gold mine finally announced a profit in 2019 after a decade of losses. The mine, which sits on one of the world’s biggest bodies of gold-bearing ore, is the most mechanised gold mine in SA. But it has struggled with a difficult geology and repeatedly missed targets. In November, however, the company was able to announce that it was cash positive for the second successive quarter and that production was up 23% year-on-year. In platinum, Implats was able to announce headline earnings of R3 billion after losing R1.2 billion in 2018.

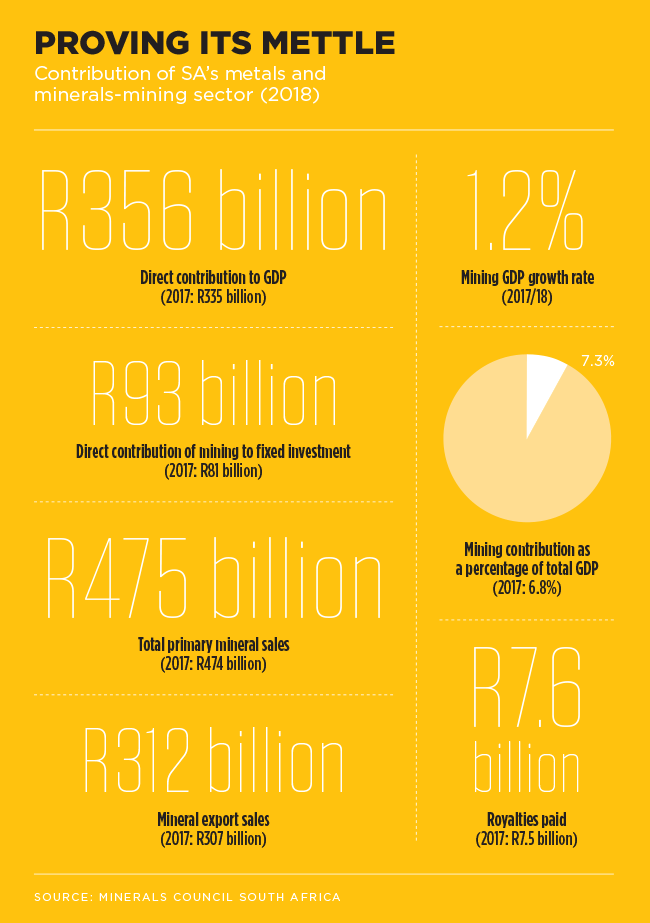

The market caps of SA’s listed gold and platinum sectors climbed 133% and 129% respectively. According to consultancy PwC, free-cash flows for SA’s listed mining sector doubled in the year to August 2019, while earnings and dividends are at five-year highs. The JSE mining index has outperformed the All Share over the past two years, while the market cap of the Top 10 companies almost doubled from R482 billion in mid-2018, to R884 billion in August 2019.

SA’s listed miners have been frustrated by the red tape around their applications to set up independent power-generating plants, mostly solar PV. The mining industry is known to account for around 600 MW of the 1.3 GW awaiting approval and sign off.

In late 2019, matters appeared to be coming to a head with the Eskom blackouts eliciting a squall of demands for faster action from the industry. ‘We must accelerate the licensing of power generation projects planned by industrial and mining companies,’ said Gold Fields CEO Nick Holland. ‘This would also give Eskom room to address operational issues at its own power stations.’

Solar-power generation would also help SA’s big miners meet carbon-emissions targets. The carbon tax, introduced in June 2019, is not particularly onerous in its current first (transition) phase. But Phase 2, to be implemented from 2023, is expected, in the absence of mitigation, to cost miners a great deal more. Harmony Gold has said that if it continues to operate as at present, it will be liable for a carbon tax of R3.9 billion under the second phase.

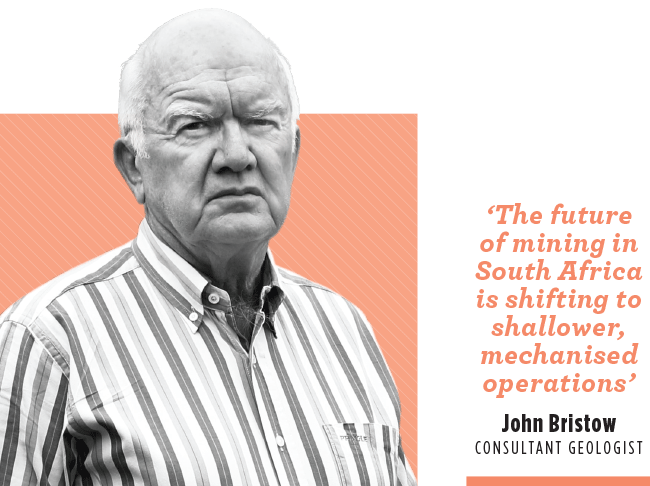

But the deep-level labour-intensive model in SA mining is a thing of the past, argues consultant geologist John Bristow. ‘The future of mining in South Africa is shifting to shallower mechanised operations,’ he says. According to Bristow, the premier assets are big open-pit mines such as Kumba’s iron ore operation in the Northern Cape and [Amplats’] Mokalakwena platinum mine in Limpopo, on the northern limb of the Bushveld igneous complex. ‘The northern limb has Platreef, which is highly desirable. As the name implies, it is flat, which means it is easy to mine,’ he says.

The changing shape of SA mining may simultaneously involve the transition from precious metals to industrial commodities. As PwC points out, the only minerals that have shown a substantial increase in volumes mined over the past 15 years are manganese, iron ore and chrome.

Internationally, the iron ore price enjoyed a very good year. After starting 2019 at about $70 per ton, it was trading at around $92 in December. But it reached $123 in the middle of the year, on the basis of production disruptions – Vale’s Brazilian production was affected by a tragic dam-wall collapse and Western Australia was hit by a tropical cyclone, disrupting both Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton.

Although SA’s sole producer, the Anglo American-owned Kumba Iron Ore, had to deal with unplanned maintenance issues, it nevertheless had an excellent year. In fact, the company’s mid-year headline earnings were up 239% on mid-2018, to R10.1 billion. In June it was able to return R9.9 billion to shareholders.

Iron ore is usually considered one of SA’s ‘big four’ minerals, alongside coal, platinum and gold. But the latest figures from the Minerals Council South Africa show that manganese and chrome are catching up. Iron ore sales in 2018 were worth R51.2 billion while manganese accounted for R44.8 billion and chrome R21.8 billion. SA has 70% of the world’s manganese reserves and accounts for around 35% of global production.

For Bristow, the Northern Cape stands out as a significant area of current and future potential. It is framed by three geographical nodes: Hotazel/Kuruman (manganese) in the north east, Aggeneys (zinc and lead) in the west near the Namibian border, and Copperton/Prieska (iron ore, copper and zinc) closer to the south-west of the province. It contains SA’s first-ever mine, a copper operation in the mountains near Springbok.

It is, of course, also the jurisdiction in which the country’s first industrial-scale mining operations developed around the Kimberley diamond strike in the mid-1860s. Small-scale diamond production still happens in the alluvial claims along the Orange river where it is renowned for the quality of the gems mined.

Vedanta’s $400 million Gamsberg zinc mine was officially opened in February 2019 even though it had in fact begun production a year earlier. It is an opencast mine, expected to produce about 300 000 tons of high-grade zinc annually, with reserves estimated at 214 million tons. Together with two zinc mines in southern Namibia, it has fuelled talk of a ‘zinc cluster’ in the region.

Indeed, the opening of Gamsberg mine was referred to by politicians as an example of why SA mining is a ‘sunrise’ and not a ‘sunset’ industry. But observers should be careful not to expect too much too soon. As things stand, ore from Gamsberg is shipped to the smelter at another Vedanta zinc mine, Skorpion, in southern Namibia, for processing. The prospects for a local smelter hinge on the future of SA’s energy supply industry.

Another promising Northern Cape project is Orion Minerals’ attempt to revive the zinc and copper project at Copperton near Prieska. Orion released a bankable feasibility study in June and is looking for investors to revive the former Anglovaal asset. At its peak, Copperton produced 1 million tons of zinc and 430 000 tons of copper. It was shuttered in 1991, a decade during which copper prices halved. According to former Anglovaal geologist Gerhard Meintjies, the original ore body had been vertical but then ‘turned flat’. This required a new phase of large capital expenditure, which Anglovaal – given prevailing market conditions – was not willing to undertake. ‘About half the deposit is still down there’ says Meintjies.

The project is ready to run, in his view. ‘Orion have finished proving up the ore body and are now working on funding,’ he says. Environmental, licensing and BEE approvals were achieved during the course of 2019. Meintjies points out that there has been virtually no exploration between the Northern Cape’s main mining nodes since the 1970s. ‘Exploration and metallurgy have been developing all the time,’ he says.

‘There are some good ore bodies out there and we’re understanding the geology better all the time’.