Coming as it does so soon after Eskom pushed pause on load shedding – and long may that last – comparisons between SA’s electricity crisis and escalating water emergency are inevitable. However, the water crisis could be considered worse ‘in that with energy there are alternatives – wind, solar – but there are no alternatives with water’, says Ferrial Adam, who heads the Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse’s WaterCAN initiative.

Cape Town came perilously close to learning that lesson firsthand in 2018 when it narrowly averted Day Zero, when the taps were predicted to run dry. Now Johannesburg and Durban are facing their own versions of Day Zero. On 10 October, eThekwini municipality announced a year-long programme of ‘water curtailments’ to reduce water use in Durban by 8.4%. While noting that the initiative is not akin to load shedding ‘where there is a schedule for water cuts at certain times’, the municipality explained it aimed ‘to avoid water shedding by bringing down the total volume used in a controlled manner’.

At about the same time, Johannesburg Water (JW) warned users, who have experienced thousands of water cuts this year as JW rotated supply, that the metropole’s water system was dangerously close to collapse. The Daily Maverick reported it would be the fourth time in a year that the municipality was facing its own Day Zero.

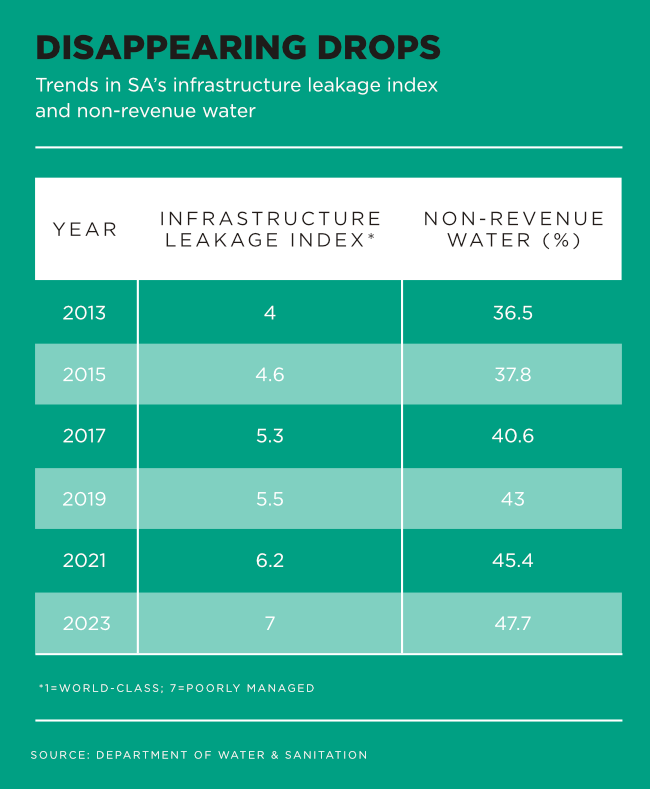

The problem is not confined to Johannesburg and Durban. Johannesburg’s estimated average for non-revenue water (NRW) – pumped water that is stolen, given away or lost to leaks – is 46%. However, according to figures from the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS), the national average NRW has climbed more than 10% from about 36% in 2013 – already higher than the global average of 30% – to 47.4% in 2023. Durban’s NRW is estimated at 54%, the highest in SA.

Compounding that problem is the damage being wrought by intense weather events. Earlier this year, Southern Africa experienced its driest February in 100 years, according to the UN, and in June in the Western Cape, 3 500 people were forced from their homes during flash floods as stormwater systems failed to cope.

Andries Fourie, senior technologist at SRK Consulting, told Business Day Earth recently that maintenance should take priority over building new dams. ‘It’s more economical to begin with the upkeep of stormwater infrastructure, restoring it to its intended capacity. This approach may not be a complete fix but offers a more practical starting point than constructing new facilities,’ he says. ‘After all, if funding isn’t allocated for maintaining essential systems, it’s improbable that it will be there for initiating new developments.’

He adds that existing structures should be monitored to ensure they are achieving the storage capacities for which they were designed. If they are becoming silted up – as invariably happens over time – then the necessary dredging must be conducted.

‘This kind of maintenance becomes more important as climate change leads to intense weather events that test – and sometimes exceed – the design limits of our infrastructure,’ says Fourie.

‘Ensuring this work is done methodically and regularly demands that municipalities rebuild their institutional memory and technical capability, much of which has been lost – especially in the smaller municipalities.’

While the long-delayed second phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water project (LHWP) is expected to come on-stream in 2028, supplying more than 400 million m3 of water every year to the Vaal dam, it won’t mean an end to Johannesburg’s water crisis.

‘LHWP will provide us with more water in that Rand Water will be able to have more water for the increased population, but that does not mean the end of our water woes,’ says Adam. ‘We need a massive focus and spending on Johannesburg’s infrastructure – 12 000 km of water pipes, 11 000 of sanitation and 87 reservoirs, and so on. JW has budgeted to fix 77.7 km of water pipes over the next five years.’ She adds that, of those 87 reservoirs, 42 have leaks, ‘so we have a long way to go’.

As for eThekwini, Faizal Bux, director at the Institute for Water and Wastewater Technology at the Durban University of Technology, told Moneyweb that the municipality ‘needs to address the non-revenue water issue very urgently, put resources in place, and get the skilled personnel to ensure that we plug the leaks. That should be the first thing that should have been done rather than it impacting now on the end users’.

Bux also highlighted the impact the water curtailments will have on business, especially during the summer tourism season. ‘It’s going to have a substantial impact on the public at large, on the economy of the city. With tourism being a major money spinner for Durban, it certainly is going to have a substantial impact.’

Considering the scale of the water crisis and the lack of wiggle room in budgets to fix infrastructure, can the private sector help mitigate the water crisis? After all, the pause in SA’s electricity supply crisis has largely been ascribed to the private sector’s uptake of solar and other renewable energy sources.

In July, Pemmy Majodina, the new Minister of Water and Sanitation, announced the formation of a governmental office that will support municipalities in establishing water-infrastructure partnerships with the private sector.

Mergence Investment Managers has been in discussions with authorities about public-private partnerships managing private water concessions, taking responsibility for the operation, repair and management of infrastructure, as well as the supply of water, which they either buy from a water board or obtain through the production of their own potable water.

Kasief Isaacs, head of private markets at Mergence, cites Siza Water in KwaZulu-Natal and Silulumanzi in Mpumalanga – two 30-year private water and sanitation concessions created in 1999. In 2018, Mergence acquired a majority equity stake in both and has since been involved in their management via a special purpose vehicle, South African Water Works (SAWW). The result has been a marked improvement in water quality and delivery to communities, he says.

‘Through the two concessions, SAWW serves more than 450 000 customers daily, and manages more than 1 500 km of pipeline and 900 km of sewerage network,’ says Isaacs, who adds that technical water losses at the SAWW concessions average 20%.

As a water activist, Adam cautions against privatisation. ‘I think that government cannot deal with the issues alone, but how businesses get involved must be monitored.’

There is scope for private involvement through ESG projects in preventing water pollution. Anton Hanekom, executive director of Plastics SA says that ‘one of its most successful initiatives is the River Catchment project across five river catchment areas around SA, […] which aims to collect litter before it reaches fragile coastal ecosystems. The project includes litter booms that primarily take the form of nets and pipes that form a barrier on the surface of the water which collects floating plastic without interfering with the movement of fish and birdlife.’

Its Operation Clean Sweep aims to make zero plastic resin loss a priority for the industry, promoting awareness among manufacturers and recyclers. ‘Spilled pellets, flakes and powder can make their way into local waterways and, ultimately, estuaries and the ocean. This isn’t just an eyesore and a litter issue – they could accidentally be mistaken for food by birds or marine animals.’

Elsewhere, private companies are helping to provide answers to the safe disposal of waste in areas that are not connected to sewerage infrastructure. Funded by a R78 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the City of Cape Town and the Water Research Commission are trialling new unsewered toilet technology in informal settlements across the city. One of the technologies is the locally developed Enviro Loo Clear system, ‘a completely natural wastewater treatment process’ that eliminates pathogens hygienically.

While acknowledging SA faces ‘a long road given the level of dilapidation’, Adam offers a measure of hope… ‘As civil society, it is really exciting that more people are becoming aware of the water crisis and are getting involved somehow.’

By Robyn Leary

Image: iStock