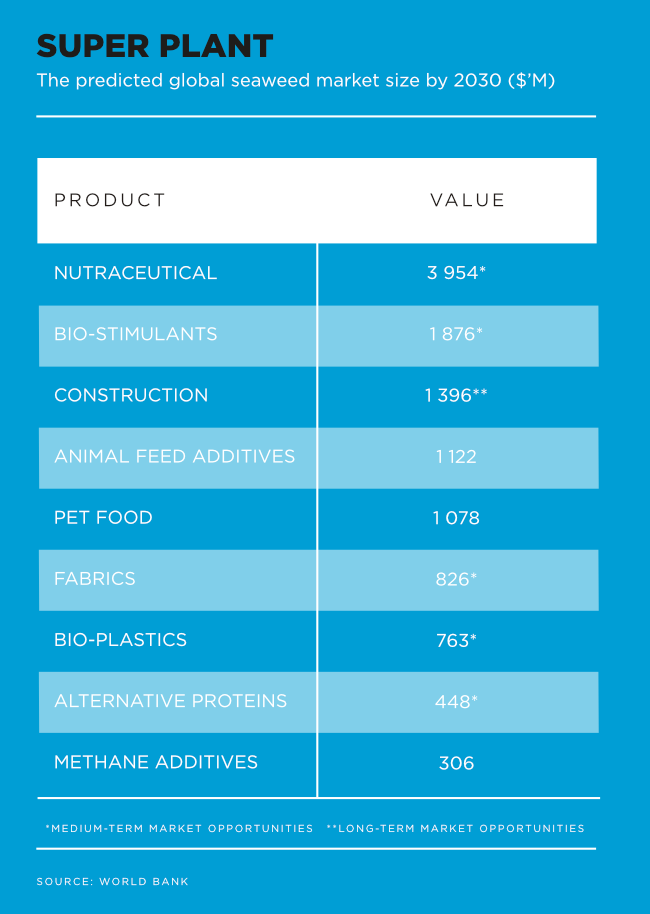

Francis Vorhies, director of Stellenbosch University’s African Wildlife Economy Institute (AWEI), has a vision. ‘Think of huge seaweed farms floating off the coasts of Africa.’ Writing in an online post to mark World Oceans Day in March 2024 and riffing on its theme, Awaken New Depths, Vorhies suggests that ‘one can only imagine what new economic opportunities might be forthcoming from this immense natural asset’.

Along with harvesting marine species, shipping, coastal tourism and renewable energy, Vorhies includes ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR). He cites research into technologies that might be used in the oceans to remove carbon from the atmosphere, including electrochemical CDR, macroalgae cultivation and ocean alkalinity enhancement.

With 38 out of 54 African states having a coastline, a 2022 World report says ‘the blue economy is at the core of economic development and competitiveness for African coastal countries. Job-creating economic sectors like tourism and food-production sectors like fisheries depend on a clean and healthy coastal environment. Ecosystem services from mangroves and coastal habitats, upon which coastal populations depend, can be supported by new revenue-generating instruments, like blue carbon’.

According to the World Bank, ‘mangroves, tidal marshes and seagrass meadows sequester and store more carbon per unit area than terrestrial forests. They also protect coastal communities from floods and storms. Properly valuing the role played by mangroves and seagrass beds – can achieve the triple win of adaptation and resilience to sea-level rise and erosion; addressing the climate crisis by storing carbon and reducing ocean acidification; and ensuring coastal communities are safer and more prosperous’.

Vorhies adds that ‘it is quite likely that ocean-based CDR technologies will be tested in Africa’s EEZ [exclusive economic zone] or in the open seas just beyond the EEZ. Hence, Africa’s blue economy strategies and policies will increasingly need to address the potential opportunities and risks of these emerging approaches to carbon reduction’.

The World Bank says the continent’s blue economy is expected grow to $405 billion by 2030 and will support 57 million jobs. It’s also an important source of food. In SA, for example, canned pilchards are now competing with chicken as the most popular protein.

But to profit from Africa’s oceans, those who depend on them have a responsibility to sustain them, by ensuring their sustainability and biodiversity.

One approach is establishing marine protected areas (MPAs,) with the UN Global Biodiversity Framework aiming to protect at least 30% of land and ocean areas globally by 2030 (30×30).

In a recent study for the WEF’s Centre for Nature and Climate, Mark Costello, a professor in the faculty of biosciences and aquaculture at Norway’s Nord University, argues that MPAs ‘represent our best strategy to reverse declining biodiversity and fisheries, because business-as-usual for global fisheries is unsustainable’.

At last count SA had 42 MPAs, about half of the national target of 10% of its oceans and considerably fewer than the 30×30 target.

In a recent GroundUp article, fisheries scientist Bruce Mann explains how MPAs support the growth of fish stocks. ‘What you see very quickly is if you stop fishing, stop harvesting and removing resources from an area, as long as it’s a good area that’s got the right habitats for those species, they respond quickly by increasing in number. You see the numbers rocketing up and the biomass increasing very quickly with fish stocks up to five or six times higher than in the fished areas outside of an MPA.’ Gradually, he adds, healthy stocks will spill over from the MPAs into legal fishing areas, which can only be good news for commercial fishers and coastal communities.

MPAs are controversial in SA, chiefly because of the impact they have on the livelihoods of coastal fishing communities, something the WWF-SA has recognised.

In a recent Business Day Earth article, Craig Smith, senior manager of WWF-SA’s marine portfolio, emphasises that any effort to declare an MPA needs to include all key stakeholders. ‘This is a difficult task, but there are some areas and approaches that could yield positive results. For example, focusing on establishing formal offshore MPAs that are not in conflict with coastal communities; and for near-shore areas consider other effective area-based conservation measures that would seek to protect small-scale fisher livelihoods, while adding conservation value.’

In the same publication, Innocent Dwayi, chair of the South African Deep-Sea Trawling Industry Association (SADSTIA), argues that ‘rather than pursuing absolute 30% ocean protection, South Africa should concentrate on rigorous fisheries management. The deep-sea trawl fishery for hake provides an excellent example of how regular stock assessments and a science-based approach to fisheries management can establish and maintain the sustainability of an economically important fishery – stocks of deep and shallow water hake are considered to be above maximum sustainable yield. This means the growth of the stocks is in balance with fishing activity and current catch levels are sustainable over time’.

The trawl fishery for hake is undoubtedly the jewel in the crown of SA’s fisheries, having been certified since 2004 by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC). It contributes about R8.5 billion to SA’s economy annually and supports about 12 400 jobs. By far the majority of fishing rights holders in the deep-sea trawl fishery for hake (98%) are SADSTIA members.

However, hake is not the only SA fishery to attain MSC certification. In September, having participated in the MSC’s In-Transition programme since 2020, tuna trading company ICV Africa became the first tuna fishery in SA to achieve MSC certification for its pole and line albacore.

‘Fishing sustainably is not only about ensuring that tuna stocks remain healthy; it is also about protecting the ocean ecosystem and the other species that our vessels interact with,’ says Michelle Bellinger, CEO at ICV Africa. ‘Our clients, and increasingly the end consumers, expect it of us. We have always believed in MSC certification and the benefits that the recognition could bring to our fishery and the work that we do.’

The South African Sustainable Tuna Association, meanwhile, has won an MSC grant to address shortfalls identified in its assessment to attain certification.

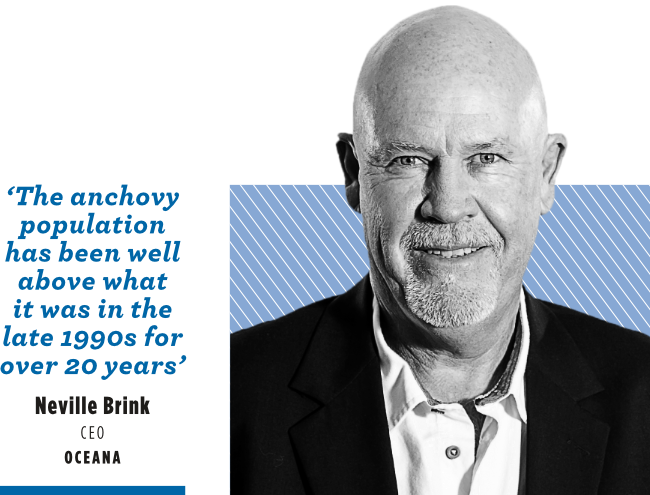

Neville Brink, CEO of Oceana, Africa’s biggest fishing company and a SADSTIA member, says that as an imperative, SA’s offshore marine resource biomass is well managed, with the majority of stocks sitting at a consistently stable level for the past 50 years.

‘As an example, the anchovy population has been well above what it was in the late 1990s for over 20 years,’ he says. ‘While we are happy with the current levels, that’s not to say that climate change isn’t altering marine dynamics and that we shouldn’t be concerned, but its impact isn’t universally negative. Some fish populations will benefit, while others will not.

‘Of course, we’re certainly not suggesting that the authorities relax their vigilance or that the industry shouldn’t be doing everything reasonably possible to ensure the sustainability of maritime resources. The future of our business depends on it.’

And the livelihoods of thousands depend on it too. Oceana, which had its origins as a small lobster fishery on the West Coast more than a century ago, now employs 3 400 people across a number of fisheries.

The company is also the producer of probably the most popular SA brand of canned pilchards, Lucky Star. While there has been some recovery in sardine/pilchard populations, the level remains below the long-term average and the resource is considered as being between a depleted and an optimal status, according to the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE). Brink says, however, that the company has ‘a zero-tolerance for illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activities that undermine the health of marine ecosystems and fish stocks, reduce ocean-related opportunities, and threaten food security’.

To reduce bycatch, its trawlers employ exclusion devices, which allow predators chasing target species to escape the trawl nets, and tori lines – streamers attached to lines or trawl cables to scare away seabirds to prevent them from being injured.

In addition, two permanent scientific advisers from the DFFE are on board Oceana’s mid-water trawls. ‘As well as recording the size and age of fish caught, they can instruct the vessel to move to another area if there is too much bycatch,’ says Brink.

Oceana’s commitment goes beyond the sustainability of its own enterprise to supporting small-scale fishers. Run in conjunction with various organisations in the public and private sectors, its Co-operative Sense initiative has trained almost 1 000 fishers belonging to 900 co-operatives to meet their basic needs and help them turn their co-operatives into sustainable SMMEs. A survey found that the participants were able to increase their income by up to 10% after completing the course.

Meanwhile, the globally recognised Abalobi app connects small coastal fishers with consumers/restaurants – while collecting valuable data about the health of the marine environment at the same time. The NPO – a finalist in this year’s edition of Prince William’s Earthshot prize – recently partnered with restaurant chain Ocean Basket to supply it with Cape bream caught by small-scale fishers using sustainable fishing methods.

Chris Kastern, Abalobi’s director of growth, says the initiative ‘helped us show that responsible fishing can be both economically viable and ecologically sound’.

As AWEI’s Vorhies writes, Africa’s blue economy ‘is indeed awakening and, with robust standards and regulations, should become a major contributor to the continent’s sustainable development’.

By Robyn Leary

Image: Gallo/Getty Images