News footage showed 40-foot shipping containers floating down the highway like blocks of Lego. Roads and bridges were being swept away by the torrential rain and burst riverbanks. Multi-storey apartment buildings and informal settlements collapsing in landslides. Warehouses and their contents destroyed by floodwater. Electricity lines broken, and sewerage plants leaking. It was the tropical storm Issa that brought the heavy rainfall that led to the floods that devastated KwaZulu-Natal in April 2022.

General insurers consider the KwaZulu-Natal floods to be the continent’s largest flooding event, causing economic losses of $3.6 billion. This includes damages to personal and commercial property, but doesn’t acknowledge the humanitarian tragedy in which 450 people lost their lives and 40 000 were displaced. When extreme weather events strike, human cost and financial cost often don’t correlate. ‘Many events with significant human impacts do not necessarily translate into a high financial toll in terms of direct damage,’ says Aon, an insurer, re-insurance and risk-management solutions firm. And, vice versa, some events have low human impacts but massive financial losses.

As SA companies grapple with how to insure their operations against risks such as electricity failures, cyberattacks and labour unrest, they increasingly also have to consider the growing threat of climate change, natural catastrophes and extreme weather in their risk profile. Reuters recently reported that due to SA’s rapidly shifting risk profile, insurance companies are curtailing their coverage and raising rates.

The frequency of natural catastrophe events in SA increased by around 50% in the decade from 2012 to 2022 compared to the preceding decade, according to Old Mutual Insure. Due to ‘extremely destructive events’ such as the KwaZulu-Natal floods and the 2017 Knysna fires, the average annual size of catastrophe claims has increased 10-fold in the same period. The company also notes that along with the large destructive events, the frequency of smaller destructive events has increased – sometimes in regions with little historical record of similar occurrences.

Rudolf Britz, chief actuary at Momentum Insure, says ‘we have seen more frequent large, aggregated events happening recently. These events vary in cause, but the financial impact seems to be larger than previous years’.

Predicting climate risks is extremely difficult, he adds. ‘Besides being able to prove that it is on the rise, being more specific in terms of area or timeline is not practical at present. Longer-term forecasts indicate that protection measures like re-insurance programmes and selective underwriting practices need to be refreshed to make sure they remain as effective as in the past.’

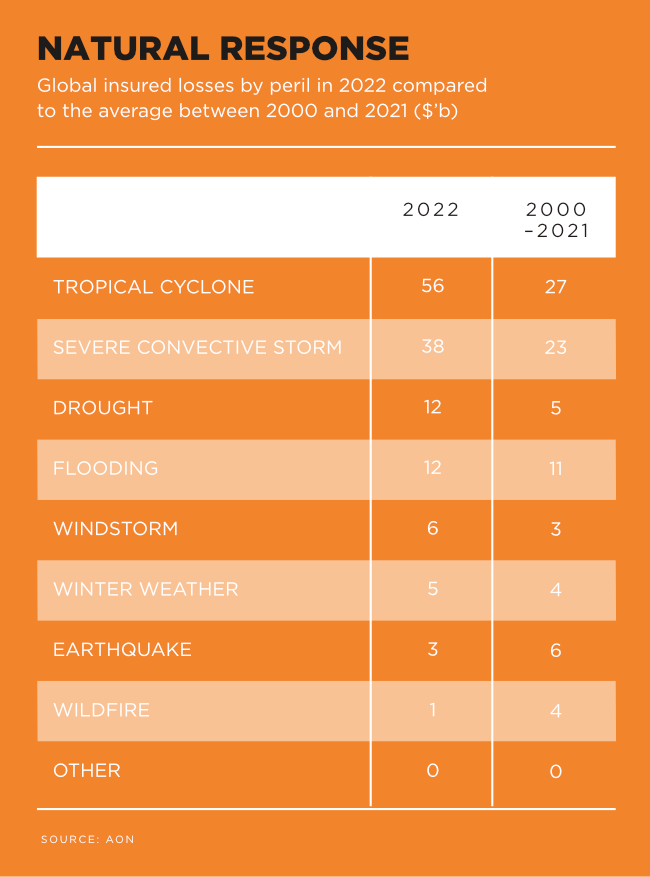

Across the globe, direct economic losses resulting from natural disasters in 2022 are estimated at $313 billion, according to Aon’s 2023 Weather, Climate and Catastrophe Insight report. ‘This is close to the 21st century average, after adjusting actual incurred damage to today’s dollars,’ it notes.

‘Though 2022 was far from record-breaking in terms of overall losses, it saw many impactful and costly events across the globe.’ As new extreme weather records were broken, many regions saw prolonged drought and scorching heat waves. The table of top 10 costliest events now features three droughts (in Europe, US and China). For SA, the 2022 KwaZulu-Natal floods were not only the costliest insurance industry event on record but, says Aon, ‘what is more concerning is the fact that only 18% of losses were insured’.

Under-insurance of risks related to climate change, natural catastrophes and extreme weather is a global challenge. Analysts say, however, that emerging economies are more vulnerable to suffer from the disruptions caused by uninsured catastrophes.

In April 2023, the European Central Bank published a discussion paper on how to better insure households and businesses in the EU against climate-related natural catastrophes such as floods or wildfires. It highlights that climate-catastrophe insurance is critical in protecting businesses as it swiftly provides the necessary funds for reconstruction after climate-related losses.

Interestingly, insurers classify earthquakes, hurricanes and tropical cyclones as ‘primary perils’ while flooding, landslides, wildfires and hailstorms are ‘secondary perils’. Storm Issa, for example, was a primary peril, which went on to induce the secondary perils of flooding and landslides in KwaZulu-Natal. Yet these definitions need reassessing, because recent trends show that claims from secondary perils are increasingly becoming insurers’ primary drivers of losses, surpassing claims from primary perils such as earthquakes and cyclones.

Recent improvements in modelling tools are allowing insurers to focus on secondary perils and create models at a more granular level, for instance through digital satellite maps.

Efforts are under way in the catastrophe-modelling industry to launch open-source data and industry-wide collaboration, as for example the OpenQuake Engine for earthquake hazard and risk modelling, or Climada-App. Developed by the European Insurance and Occupational Pension Authority, Climada-App may have potential as a useful climate risk modelling tool, says Ishkar Singh, consulting actuary at Milliman, a global provider of actuarial products and services.

‘There is not yet a robust solution with parameters calibrated specifically to South Africa, but the Climada tool is, however, open source and so there is the capability to adapt this to South African insurers.’

He says that in practice, insurers could use Climada-app to perform climate change materiality assessments. ‘This would involve evaluating the materiality of the impact of climate change risk on an insurer and allow for climate change scenarios in an insurer’s own risk and solvency assessment.’ Such an assessment, called ORSA, is a requirement of the Prudential Standard and must be completed at least annually in SA, says Singh.

The country’s largest non-life (or short-term) insurer is Santam. ‘We source risk data from provincial government, research institutions or similar entities to align with the data used by the likes of spatial planners,’ says Thabiso Rulashe, head of strategy and investor relations at Santam Insurance. ‘When we invest in creating risk data, site-specific modelling is carried out by industry professionals. High-quality risk data provides an indication of areas that will be exposed to events with specific probabilities of occurrence, which allows for property-level underwriting for perils like flooding.’

The modelling also indicates when insurers regard a risk as too high to take on a certain client. This is already happening in California and Florida, where some areas have become uninsurable because of their high wildfire and hurricane risk.

‘When property and content are exposed to a peril and the risk data indicates the property will be affected by an event with a 1:50-year probability of occurrence – or more frequently – the property cannot be insured against that specific peril,’ explains Rulashe. ‘This is commonly seen with river flooding and coastal flooding exposures.’

Insurance companies are crucial in guiding companies on how to comprehensively protect themselves against climate risk. This includes assessing and understanding the range of physical, operational and financial climate-related risks for a specific business, and finding ways to reduce and mitigate these.

‘Insurance can, for example, help South African businesses, via partnerships with government and municipalities, to create the risk data required for spatial-planning purposes,’ says Rulashe. ‘High-quality risk data should inform the spatial planning of new developments.’

This could pre-empt property damage, which, together with business interruption, is one of the most common risks as a result of natural hazards and extreme weather events such as floods, storms, thunderstorms and droughts, according to the 2023 Allianz Risk Barometer – an annual survey of large and medium-sized companies about their key business risks.

Other climate-related risks include the threat of legal and liability risks, due to the complex regulatory framework around the world, increasing disclosure requirements, and the threat of greenwashing accusations or climate lawsuits. In addition, there are transformation (also called transition) risks resulting from new market conditions or product requirements as the markets shift away from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Respondents in the Allianz survey are adopting carbon-reducing business models, such as switching to renewable energy sources, to combat the direct impact of climate change. Furthermore, their actions include developing a dedicated risk-management strategy for climate risks; and creating contingency plans for climate change-related eventualities, such as assessing critical systems and resources.

‘Insurers are exposed to climate risks like everyone else, but there are some areas where they are well positioned to have a positive impact on mitigating the worst of climate change and easing company and individual adaptations to a warmer, more perilous world,’ says David Kirk, MD and consulting actuary at Milliman in Africa. ‘Insurance underwriters have long advised business on where fire extinguishers are needed in their business. Now, insurance underwriters may be able to advise on climate-adaptation practices as part of their risk-rating process. This can help businesses understand their exposures.’

For many SA-based companies, recent extreme weather events such as the KwaZulu-Natal floods, Knysna fires, and the Western Cape floods in September 2023 have served as a wake-up call that climate risk must be treated as a financial risk. Insurance is the first line of defence. It can limit financial losses by keeping businesses running and managing risk better, so that shipping containers won’t turn into blocks of Lego, and SA’s warehouses and business properties will be protected during the next flood – or any other extreme weather event in the future.