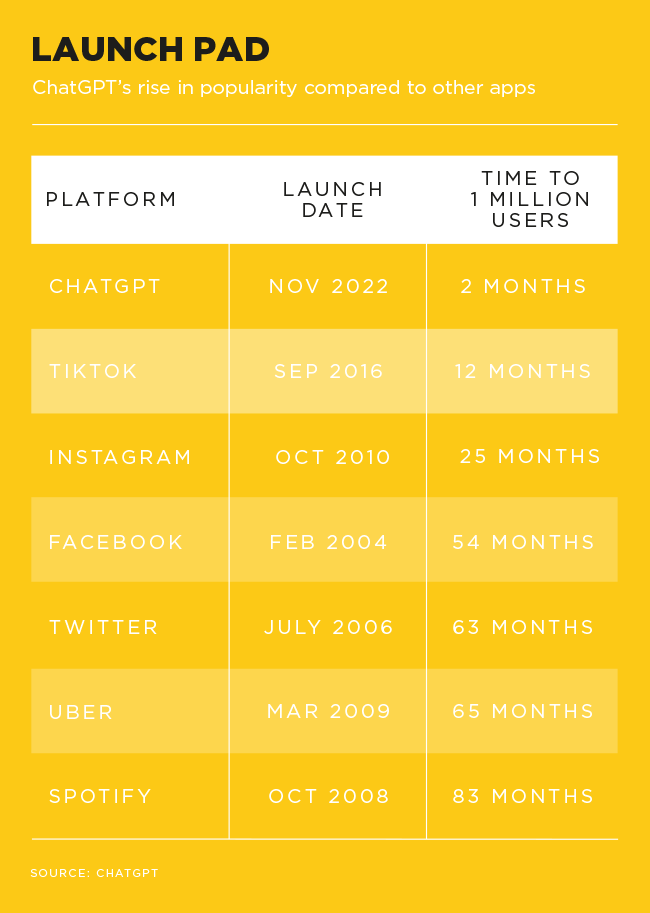

Tom Scott is scared. Normally, the UK Youtuber shares upbeat, offbeat videos with his nearly 7 million subscribers – videos with titles such as I Rode a Giant Mechanical Elephant; You Can Too. But in February 2023, as OpenAI’s ChatGPT AI platform was taking the tech world by storm, Scott posted an uncharacteristically sombre clip.

After playing around with ChatGPT, Scott reflected that ‘I’ve been complaining for years that it feels like nothing has really changed since smartphones came along… And I think that maybe, maybe, I should have been careful what I wished for’. The AI tool, he said, represents a massive collective step into the unknown. ‘That’s where the dread came from – the worry that suddenly I don’t know what comes next. No one does.’

Gerhard Oosthuizen, chief technology officer (CTO) at SA fintech firm Entersekt, has a similar take. ‘If you haven’t played with the newer AI chat and art generators, then you must at least have heard of them,’ he says, pointing to how natural language text generators such as ChatGPT and image generators including DALL-E 2 are ‘testing our limits when it comes to differentiating between machine and human outputs’.

Oosthuizen notes that these technologies offer a huge opportunity for businesses’ self-service and omni-channel communication efforts, but then sounds a warning… ‘As attractive as the additional automation may seem, security leaders will also need to gear up to deal with the darker side of the technology – or, rather, of the humans who use it for their nefarious ends.’

As Gerhard Swart, CTO at cybersecurity company Performanta, puts it, ‘ChatGPT won’t make a newcomer good at cybercrime coding – they still need a lot of experience to combine different codes. But an AI could generate code at a pace and scale that would help experienced criminals do more, faster. And it could help inexperienced people get better access to the many crime tools available online and learn how to use them. I don’t think the concerns about cybercrime are overhyped. They’re just not that simple, for now’.

However, the biggest cybersecurity threat posed by AI platforms such as ChatGPT and Google’s Bard is not so much that they’ll help cybercriminals write nastier malware. After all, they’ll also help cybersecurity firms write better security patches. No, the real problem – the scary stuff that has people like Scott worried – is that we don’t yet know the full extent of AI’s capabilities. And what we do know is scary enough on its own.

Log in to ChatGPT (it’s free), and you’ll quickly get a sense of how its language-learning model works. Ask it, for example, to ‘write a Trevor Noah joke in the style of Jerry Seinfeld’, and it’ll do exactly that – quite convincingly. Ask it to ‘write a breakup song in the style of the Rolling Stones’ or ‘write a birthday message in the style of Cyril Ramaphosa’, and you’ll get uncannily accurate results.

(Worried yet? Just days after ChatGPT’s launch, Twitter CEO Elon Musk called it ‘scary good’.)

‘If we strip ChatGPT down to the bare essentials, the language model is trained on a gigantic corpus of online texts, from which it “remembers” which words, sentences and paragraphs are collocated most frequently and how they interrelate,’ Kaspersky’s Stan Kaminsky writes in an online post for the cybersecurity firm. ‘Aided by numerous technical tricks and additional rounds of training with humans, the model is optimised specifically for dialogue. Because “on the internet you can find absolutely everything”, the model is naturally able to support a dialogue on practically all topics – from fashion and the history of art, to programming and quantum physics.’

That’s why the platform is proving so popular among students, who can ask ChatGPT to ‘write a 300-word essay on the 1917 Russian Revolution’, and then sit back while the bot churns out their homework in just a few seconds. It’s not original work, but who cares? When you’re copying someone else’s homework, all you need is a good copier. And AI is nothing if not a really, really good mimic.

That’s why Oosthuizen urges caution from a cybersecurity perspective. Using generative AI, cybercriminals can generate emails that mimic the language and style of company executives, or even clone people’s voices and faces. ‘It is feasible to use these machines to simulate a voice, with just a small sample, which could then be used to bypass voice recognition or in payer manipulation fraud,’ he says. ‘Of course, the art generators are ideally positioned to help generate synthetic IDs with face images, voices and back stories that do not actually exist, but look incredibly real.’

It’s already happened. According to a Forbes report, in early 2020 a bank manager in Hong Kong received a phone call from a company director whose voice he recognised, asking the bank to authorise $35 million in transfers. Emails sent at the same time confirmed that the request was legit, and so the bank manager made the transfers. What he didn’t know, Forbes reports, ‘was that he’d been duped as part of an elaborate swindle, one in which fraudsters had used “deep voice” technology to clone the director’s speech’.

Patrick Hillmann, chief strategy officer at cryptocurrency exchange Binance, experienced another side of the scam. ‘Over the past month, I’ve received several online messages thanking me for taking the time to meet with project teams regarding potential opportunities to list their assets on Binance.com,’ he writes in an online post.

‘This was odd because I don’t have any oversight of, or insight into, Binance listings, nor had I met with any of these people before. It turns out that a sophisticated hacking team used previous news interviews and TV appearances over the years to create a “deep fake” of me. Other than the 15 pounds that I gained during COVID being noticeably absent, this deep fake was refined enough to fool several highly intelligent crypto community members.’

Fortunately, according to Performanta’s Swart, ‘the cybersecurity world knows these tricks. Modern security can deal with phishing and impersonation attacks. It can detect and prevent the type of tricks that generative AI generates. But to create that advantage, people and companies need to take security more seriously’. Kaspersky’s Kaminsky, meanwhile, defaults to cybersecurity’s two golden rules. ‘We can only recommend our two standard tips – vigilance and cybersecurity awareness training,’ he writes. ‘Plus a new one. Learn how to spot bot-generated texts. Mathematical properties are not recognisable to the eye, but small stylistic quirks and tiny incongruities still give the robots away.’

Yet what if the person who’s scamming you looks like a trusted colleague, writes like a trusted colleague and sounds like a trusted colleague? AI is learning so quickly and evolving so rapidly that soon you won’t be able to believe your own eyes and ears. And this is just the beginning. No wonder Scott is so scared.