No longer merely concerned with staving off burnout, the corporate world has had to radically re-evaluate its relationship with its people in the wake of the economic, psychological and lifestyle disruption of the past few years. Hence the increasing prominence of chief wellness officers (CWO) to address employees’ mental health and create a more caring, supportive company culture. While they’re not new – some reports on the role go back as far as 2009 – and have been a feature in many US hospitals for some time (in response to high staff burnout rates), they didn’t quite take off until recently, when workplaces across the globe were called on to evolve at breakneck pace on an unprecedented scale.

Jen Fisher, who claims the title of being the first-ever CWO in the professional services industry, has been Deloitte’s CWO for seven years. She says that her programmes for ‘embedding well-being into all aspects of the organisational strategy’ have been major contributors to the company’s recent inclusion on several prestigious ‘best place to work’ and ‘best prospects for professional growth’ lists.

Rachel Fellowes, who runs her own well-being consultancy, recently joined UK-US multinational financial services firm Aon as its new CWO, overseeing the well-being of more than 50 000 employees. ‘Well-being is here for the long term. It’s not a fad,’ she says. ‘Very rarely now do organisations ask, “do we need well-being?”. Now the question is “where are we on the well-being maturity curve, and how do we start to move forward?”.’

CWOs – also known as happiness or resilience officers, well-being managers, or even ‘head of humanising business’ – aren’t always hired in permanent positions. A subset of professional coaching qualifications has arisen to meet this need, so companies can now consult a CWO on a retainer or consultative basis, rather than making it a permanent position within the organisation.

Kevin Jooste, principal industrial psychologist at Cape Town-based PsyQ Consulting, identifies two factors beyond the ‘obvious emotional and cognitive fallout consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic’ that have led to the renewed focus on the role of the CWO – the mass uptake of remote-working practices, and the hopes, aspirations and life goals of newer generations who are now entering the workplace, and how these relate (if at all) to the strategic imperatives of the organisation.

‘Organisations now face a perfect storm of sorts in that national lockdowns provided the opportunity for talent to pause and take cognisance of the nature and impact of work in their lives, while at the same time experiencing scope creep and role ambiguity like never before,’ says Jooste. ‘In some instances this led to the creation of animosity towards employers, perhaps contributing to the mass resignations seen in more Western countries. In South Africa, where employment opportunities are more scant, we often start to see heightened presenteeism [working while sick or burnt out], which can arguably be more damaging to the bottom line than a resignation.’

Jooste adds that people have reached a saturation point regarding toxic workplace cultures and workplace-based psychopathology. ‘In general, a toxic workplace has now become a deal-breaker for many talented individuals. The difficulty faced by organisations now is that a bigger pay cheque and better fringe benefits are often no longer sufficient to retain talent, and that people are no longer just quitting their jobs; they are quitting toxic and abusive cultures.

‘Lastly, the generational gap is becoming more profound at work, especially in terms of career anchors, organisational loyalty and work-life balance. Younger talent value personal pursuits, family and leisure time like no generation before them, and this necessitates that organisations change preconceived notions of undying loyalty and commitment from the workforce.’

‘Lastly, the generational gap is becoming more profound at work, especially in terms of career anchors, organisational loyalty and work-life balance. Younger talent value personal pursuits, family and leisure time like no generation before them, and this necessitates that organisations change preconceived notions of undying loyalty and commitment from the workforce.’

Along with phrases like ‘blue sky thinking’, ‘beep me’ and (we hope) ‘let’s circle back on that’, it seems the catchphrase ‘work-life balance’, too, is going the way of the dodo. All hail the new aspiration – work-life integration, something most employers, and employees, will need assistance with.

According to Nikki Bush, a corporate speaker, author and consultant on disruption, leadership, resilience and ‘how to squeeze “happy juice” into an organisation’, there is no such thing as balance.

‘Corporates and businesses are finally seeing that there is one human being, and it’s a whole human being who should be bringing their whole selves to work every single day,’ she says. ‘They shouldn’t be leaving half of themselves at home and, when they go home, they shouldn’t be leaving half of themselves at work. I have watched over the years as people slice and dice themselves and only take certain parts of themselves home and certain parts of themselves to work.’

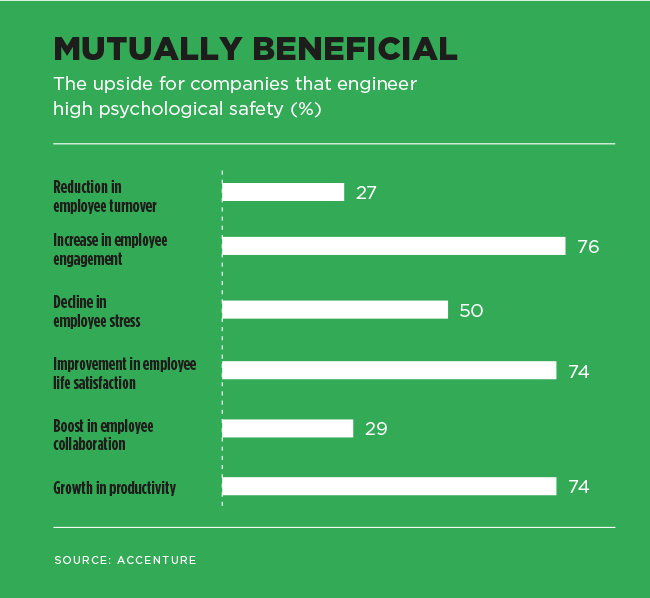

Integration is part of well-being, she adds, and it’s a result of feeling safe enough to take your whole self to the office, otherwise known as psychological safety. ‘This is a major piece of the puzzle in a business today – leaders actually creating psychological safety, because the research is showing us that people will stay for psychological safety before the salary. People like to work in an environment where they feel they are not under threat, because the world itself is so threatening out there today. When people feel safe, they give more. So the chief wellness officer is really about creating psychological safety for employees.’

To be effective, the CWO position should be a C-suite position, rather than a mere manager, ideally at board level. The board represents a strategic opportunity to start crafting organisational culture, while matching strategic action to the motivations of those who staff the board, says Jooste. The CWO holds a strategic role in informing which people-related decisions should be prioritised to have a positive impact on the collective organisational psyche and the bottom line. In essence, the CWO represents the key link between strategic objectives and underlying human issues and needs, and how to meaningfully merge these two concepts while ensuring substantive stakeholder buy-in.

Typically, companies should look for a candidate with ‘considerable experience in working with people issues, integrating people and business needs, and a background in depth psychological approaches would be preferable’, he says. ‘They should have the capacity to understand both the dynamics and boundaries of human behaviour within an organisational setting, which are often at the core of organisational dysfunction, and have a proven track record of competence in organisational development.’

What kinds of programmes might a CWO implement? At Deloitte, a few of the changes established by Fisher include an employee ambassador network (‘well-being wizards’); collective disconnect days, as part of Deloitte’s technical hygiene strategy; a revamp of the well-being subsidy benefit to include new options such as meditation and massage, as well as more financial support; and a learning programme to help employees embed well-being behaviours in their daily lives.

In an SA context, diversity sensitivity is imperative, according to Jooste. ‘When attempting to create psychologically safe work environments, the interventions planned must cater to the unique experiences, values, norms and implicit practices of all those who engage with them.

‘This is particularly salient when it comes to psychological well-being, and the practices associated with psychological healing. It’s only through the creation of truly inclusive initiatives that meaningful change can occur.’