In May 2020, during the panic of SA’s first wave of COVID-19 infections, three government departments partnered to power Pretoria’s beleaguered 1 Military Hospital. The departments of Science and Innovation (DSI), Defence, and Public Works and Infrastructure deployed seven hydrogen fuel-cell units.

For the healthcare workers at One Mil, the deployment of those hydrogen cells was a godsend. To green-energy analysts, it represented the latest in a steady move towards hydrogen as a safe, viable and attractive fuel source. It also confirmed hydrogen’s overdue move into the energy mainstream.

Pointing to the national Hydrogen South Africa strategy, approved by Cabinet in 2007, the DSI recently reported on how hydrogen fuel cells have matured to the point where the technology is now suitable for both mobile and stationary applications. As the department points out, ‘if the hydrogen gas is produced from renewable energy, such as solar photovoltaic or wind energy, through water electrolysis, the energy production process has a near-zero carbon footprint. Hydrogen fuel cells coupled with renewable energy thus have the potential to decarbonise both the energy and transport sectors, with a positive contribution to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions’.

The DSI underlines another ‘notable advantage’ of hydrogen fuel cells, which is their modular nature. This allows them to be moved around, indicating ‘the potential to play an important role in disaster management and distributed-energy generation in remote areas’.

SA’s mining houses have been paying close attention to the development of hydrogen fuel cells, hoping to use the technology to power their vehicles and underground ventilation equipment. In July 2020, Anglo American’s Amplats began the process of fitting 400 of its mine haulage trucks with hydrogen-powered engines.

‘We are developing a technology that we believe will set a new trajectory for zero emissions,’ Amplats spokesperson Jana Marais said at the time, adding that the hydrogen trucks could ultimately cut emissions at Anglo’s mines to zero.

JSE-listed Impala Platinum (Implats) then announced an investment into the AP Ventures Fund II. According to Morné van der Merwe, corporate and M&A head at law firm Baker McKenzie, the fund invests in solutions that are critical to Africa’s sustainable energy future. ‘Such solutions must take into account the energy transition and the global drive towards a decentralised, decarbonised and secure energy supply that addresses climate change and stimulates economic growth,’ he says.

‘This exciting investment will enable the development of hydrogen technologies that can lower energy costs, increase the power system’s flexibility and facilitate the decarbonisation of African industries.’

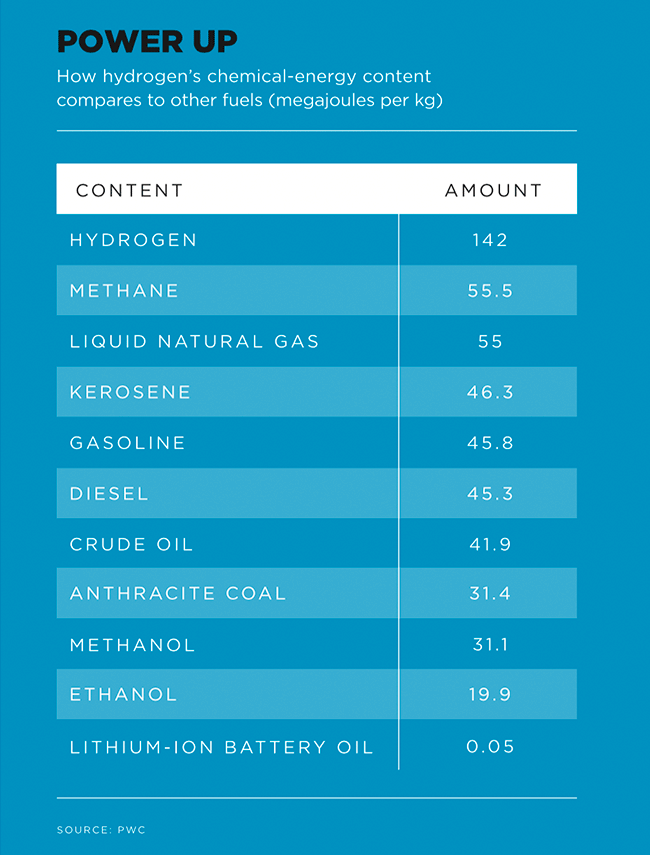

It makes sense for platinum miners to pay special attention to hydrogen fuel cells. After all, while the cells use hydrogen gas as an input fuel, they produce electrical energy through an electrochemical reaction with a platinum-based catalyst. The only by-product is pure water. Hydrogen, the most common element in the universe, is of course the H in H2O.

PwC SA’s inaugural Unlocking South Africa’s Hydrogen Potential report, released in late 2020, outlines how hydrogen is broadly categorised into three types – grey, blue and green – based on the quantity of carbon emitted in their production and the production process itself.

‘Grey hydrogen is produced from natural gas (through steam methane-reforming) or from the gasification of coal,’ the report states. ‘Although grey hydrogen still accounts for most of the global hydrogen supply, its relative high-carbon intensity has seen a decline of its popularity. Blue hydrogen is produced from the same carbon-intensive feedstocks as with grey but is twinned with some type of carbon-capture technology, thus vastly increasing the green credentials of the final hydrogen gas. Blue hydrogen allows companies or countries that have previously invested into grey hydrogen production to elongate the lifespan of their assets and allow for the continued utilisation of already identified fossil-fuel resources.’

Most investor attention, however, is focused on green hydrogen. ‘This production method utilises electricity generated through renewable energy (wind, solar or hydro) and splits pure water through an electrolysis process into hydrogen and oxygen molecules,’ according to the PwC report. ‘As the cost of renewable energy and electrolysis technology has plummeted in recent years, green hydrogen is ever increasingly reaching parity with its more carbon-intensive counterparts.

‘In countries with high renewable-energy potential such as Saudi Arabia, Australia and Chile, green hydrogen has already become the preferred investment choice.’

The PwC report acknowledges, however, that ‘investment in blue hydrogen may well be the stepping stone to developing a fully decarbonised hydrogen economy’.

Mkhulu Mathe of the CSIR admits that fuel cells are ‘not without their challenges’, citing the cost of the catalyst and its inverse correlation to the number of units produced. ‘The use of hydrogen as a fuel has several disadvantages mainly related to its safety in transportation and storage,’ he adds.

‘This concern has seen the adoption of codes and standards for using hydrogen as a fuel in vehicles, as well as in portable and stationary applications.’ However, Mathe says that ‘for South Africa, the development of fuel-cell technology is an opportunity to beneficiate its platinum reserves in addition to its exports’.

Around the world, research and product development continue apace. Global motor manufacturer Toyota recently relaunched its Mirai hydrogen fuel-cell car, which boasts a 30% greater range (the new model can go 800 km without refuelling), in its latest bid to promote the technology amid the growing demand for zero-emission electric cars. ‘The use of hydrogen is going to be an important factor in achieving carbon neutrality,’ says Mirai chief engineer Yoshikazu Tanaka. He adds that the car represents a ‘departure point’ for a broader use of hydrogen fuel cells beyond cars.

Several maritime companies are working to develop the technology in the shipping sector, with Australian-based Global Energy Ventures, for example, entering a two-year project with Ballard Power Systems to design and develop a hydrogen fuel-cell system for a large-scale ocean-going hydrogen transport ship.

Aerospace giant Boeing, meanwhile, is taking a more circumspect approach to the notion of hydrogen-powered aircraft. In a Q4 2020 earnings call in January 2021, Boeing CEO David Calhoun said that the industry is still some way from harnessing the technology.

‘I have a fair amount of experience with hydrogen; our company has an incredible amount of experience with hydrogen. At least in the size of airframe that we are all talking about,’ he told investors. ‘We experiment at the low end, but that’s not going to be a meaningful market here. And the advent of sustainable fuel already, already we’re capable of living with that sustainable fuel.

‘I believe that’s going to be the 15-year answer to 2050 guidelines and approaches because we have all worked with it; experimented with it. We know it works, and now we need to develop a supply line for it. But I believe it’s the only answer between now and 2050.’

That’s a long time to wait; and others aren’t quite as patient. PwC analysts found that at the beginning of 2020, the global hydrogen project pipeline across grey, blue and green projects stood at $95 billion. They argue that SA has the competitive advantage to produce and export green energy.

‘South Africa has world-class renewable potential that can be leveraged to supply clean energy to the world and transform the domestic economy,’ says Jonathan Metcalfe, PwC’s Strategy& Africa South market lead of hydrogen. Fuel cells, he adds, are just the beginning. ‘Hydrogen has the ability to revolutionise the entire energy space. For South Africa, focusing on fuel cells alone is missing the bigger opportunity.’

All the same, those fuel cells are a good place to start.